Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel announced on Monday that he was delaying his government’s contentious plans to overhaul the judiciary, which have set off civil unrest and work stoppages and incited one of the deepest domestic crises in the country’s history.

The concession was announced amid a toxic and emotional national discourse on the judicial overhaul that many had feared could lead to political violence or even civil war.

The Prime Minister’s decision to postpone the changes followed a night of turmoil across Israel, with raucous street demonstrations erupting on Sunday night after he dismissed defence minister Yoav Gallant, who had called for a halt to the process.

Israel’s major universities shuttered their classrooms on Monday morning in protest, while strikes rippled across the country. Many anti-government protesters marched in the direction of Netanyahu’s home, blocking roads and filling squares in central Jerusalem.

Some similarities do exist between the occasional attempts in India to replace the Supreme Court collegium with an alternative in which the executive has a say in the selection of the judges. Recently, some figures, including law minister Kiren Rijiju, associated with the Narendra Modi government had started to snipe afresh at the prevailing process to select judges.

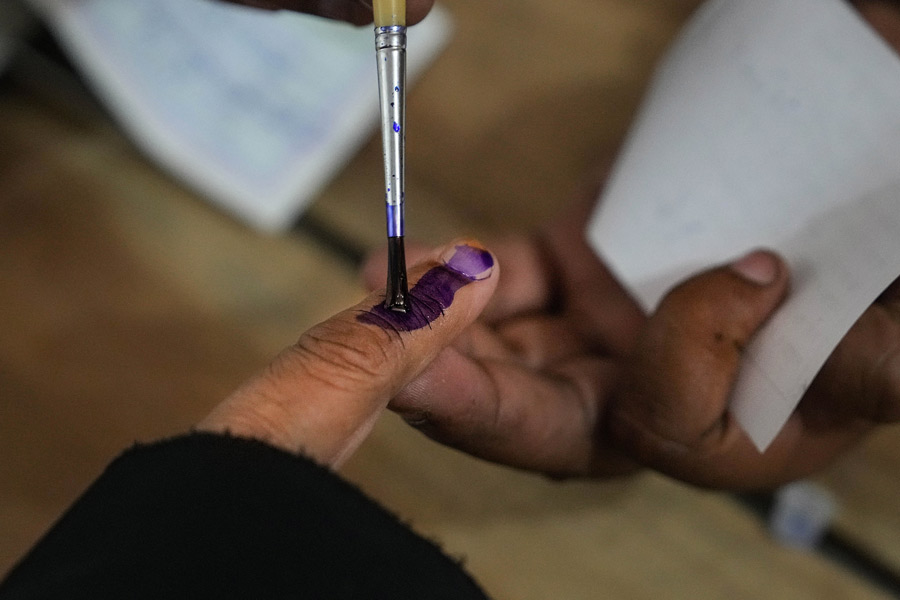

For the past seven decades, Israel’s nine-member appointments committee, made up of five legal professionals and four politicians, generally had to reach an agreement to select Supreme Court judges with the required majority of seven. The Netanyahu government’s contentious new proposal would have given government appointees an automatic majority on an expanded committee of 11. Critics fear the changes will remove important checks and balances on the government and erode democracy. Netanyahu is standing trial on corruption charges before the same judiciary that would be subject to his government’s overhaul.

Supporters say the overhaul would curb the influence of an overreaching and unelected judicial bureaucracy. The judicial plan has also caused unease among soldiers and provoked rising criticism from influential Jewish Americans and the Biden administration. That added to a groundswell of opposition from another influential group within Israeli society: the military reserve. Thousands of reservists, who play a key role in certain missions, including the air force, had either threatened to refuse service if the overhaul went ahead or had already stood down.

The chief of military staff, Lt Gen. Herzi Halevi, recently warned government leaders that so many reservists were skipping duty that the military was close to reducing the scope of certain operations. Netanyahu reversed his position after a hard-line member of his coalition, Itamar Ben-Gvir, said he was open to delaying a vote on the government’s bid to weaken the judiciary, removing what had been viewed as the biggest obstacle to any postponement. But Ben-Gvir made it clear that he was not backing down. “The reform will pass,” he said on Twitter.

Speaking on national television, Netanyahu said that he would delay final voting in Parliament on the legislation that would allow the government to assert greater control over the Supreme Court. “When there is a possibility of preventing a civil war through dialogue, I, as the Prime Minister, take a time out for dialogue,” Netanyahu said. The overhaul has become a proxy for much deeper social disagreements within Israeli society related to the relationship between religion and state, the future of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, and ethnic tensions among Israeli Jews. Orthodox Jews and settlers say that the court has historically acted against their interests and that it has for too long been dominated by secular judges. Jews of Middle Eastern descent also feel underrepresented on the court, which has mostly been staffed by judges from European backgrounds.