A series of coordinated attacks on Easter Sunday in Sri Lanka shattered the peace in a country that has suffered a long history of sectarian tensions.

During a decades-long civil war, which ended in 2009, the primary fault line in the country was between the Sinhalese Buddhist majority and minority Tamil groups. But the bombings, claimed by the Islamic State and targeting Christian minorities, have little to do with these historical tensions.

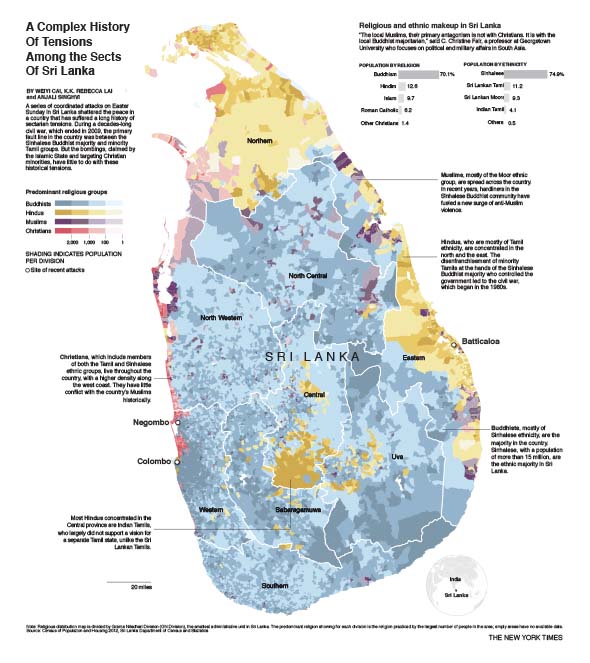

Sinhalese, with a population of more than 15 million, are the ethnic majority in Sri Lanka and are mostly Buddhists. They live in the western and southern regions of the island. The Tamils occupy most of the north and parts of the eastern coast. The disenfranchisement of minority Tamils at the hands of the Sinhalese Buddhist majority who controlled the government led to the civil war began in the 1980s.

The strain between the Sinhalese Buddhists and the Tamils has dampened significantly since the war ended in 2009. In recent years, hard-liners in the Sinhalese Buddhist community have fuelled a new surge of anti-Muslim violence. Last year, the government declared a state of emergency after a number of mob attacks by Sinhalese against Muslim businesses and houses.

It was not immediately clear how Sunday’s bombings fit into the larger dynamic of the country, and experts suggested that the attacks actually contradict the country’s historical conflicts.

A relatively unknown radical Islamist group, National Thowfeek Jamaath, is believed to have carried out the attacks, with help from international militants, Sri Lankan officials said Monday.

“The local Muslims, their primary antagonism is not with Christians. It is with the local Buddhist majoritarian,” said C. Christine Fair, a professor at Georgetown University who focuses on political and military affairs in South Asia.

The group was mainly known for vandalising Buddhist statues until now.

“Most of the people who were killed are Sri Lankan Christians, who have nothing to do with traumatising or brutalising the Muslims of Sri Lanka,” Fair said.

The choice to target Christian communities, who largely had little conflict with the country’s Muslims, along with the scale of the attack, suggested the involvement of a global jihadi with a broader anti-Christian agenda, according to Ajai Sahni, executive director of the Institute for Conflict Management in New Delhi.

The Islamic State issued a statement more than two days after the attack claiming responsibility. The group’s Amaq news agency called the bombers “Islamic State fighters” and shared a video of the eight men — apparently the Sri Lanka attackers — pledging allegiance to the group.

c.2019 New York Times News Service