Safe to say that when Mamata Banerjee won the historic Bengal elections of 2011 and promised to turn Calcutta into London, she did not mean to make real olden rhymes of falling bridges, et al. And yet, over the past few years Calcutta has been experiencing an acute bridge crisis. In 2013 one flank of the Ultadanga Flyover collapsed, three years later an under-construction bridge collapsed in the Girish Park area, in 2018 the Majerhat Bridge caved in, and for the last 49 days the Tala Bridge has been in a state of partial shutdown.

The constantly expanding bottle gourd-shaped city of Calcutta stretches approximately 30 kilometres from north to south — as the crow flies — and 10 kilometres from east to west. It has a population of 4.6 million and a total of 20 bridges. This includes metal bridges, concrete bridges, flyovers and railway overbridges. According to Amitabha Ghoshal, who is president of the Consulting Engineers Association of India (CEAI), a body that has expertise in inspection, investigation and repair/rehabilitation of bridges, a bridge is that which runs over a waterbody or railway track while a flyover passes over roads. Both criss-cross the cityscape and work like hyphens, yanking close distant points.

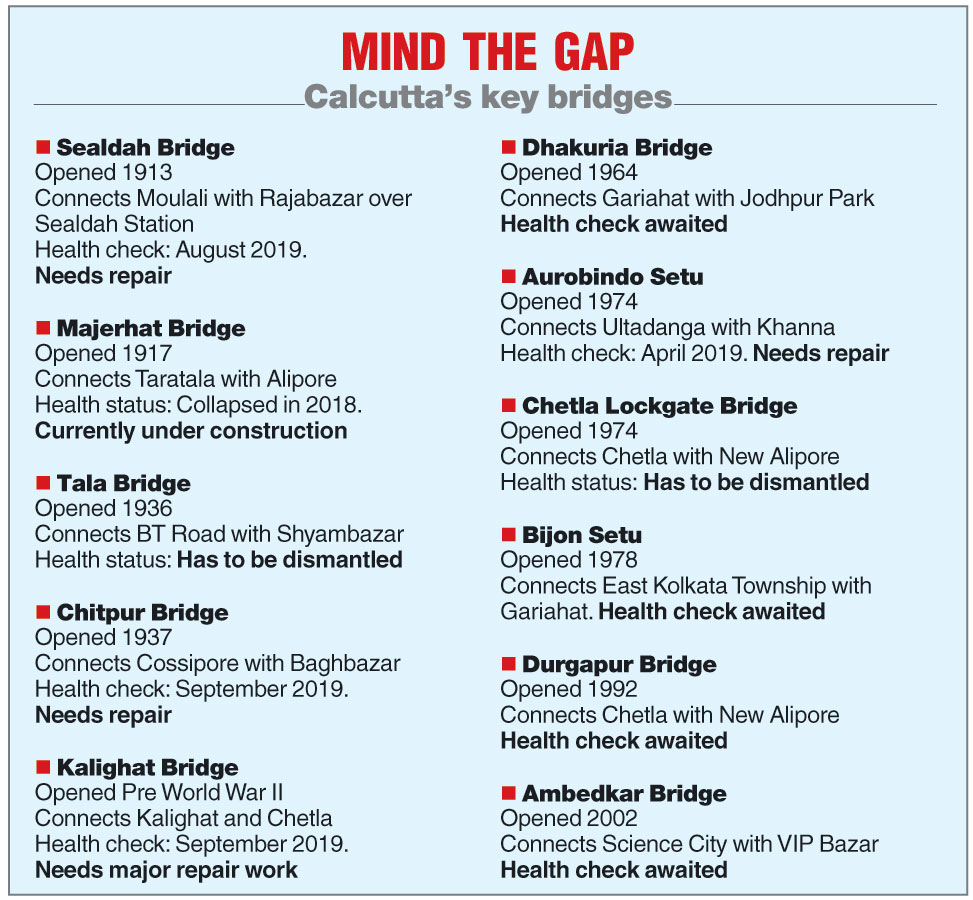

The Majerhat Bridge connects south Calcutta’s Behala to Kidderpore. The Tala Bridge is a crucial north-south corridor. Close to it lies the Belgachia Bridge that serves as an alternative route when the Tala Bridge is shut. There is the Sealdah Bridge that connects the north to the heart of the city. The Aurobindo Setu is the lifeline of those commuting from Khanna via Ultadanga to Salt Lake and Baguiati. The Dhalai Bridge connects South 24-Parganas to the rest of the city and so on and so forth. The oldest of these is the Sealdah Bridge built in 1913, and the newest is the Maa Flyover built in 2015. At 823 metres, the longest bridge is Vidyasagar Setu and the shortest is the iconic Howrah Bridge, which is all of 450 metres.

A bridge is not just a bridge. It is not about the traffic that goes over it; it is also about what lies beneath and around. A bridge is the sum total and more of each of the human lives it impacts. That is why a falling or already fallen bridge is more than an inconvenience.

DOWN UNDER: Engineers inspect the broken belly of Tala Bridge Sanat Kumar Sinha

“I have to travel to Dalhousie every day for work. It takes me two hours in the morning and another couple of hours in the evening,” says Archana Singh, who lives in Parnasree in Behala. Since the Majerhat Bridge collapse, she and her husband have started to use the Bailey bridge, but it is an onerous commute. The Bailey bridge was built hurriedly in the wake of the Majerhat Bridge crisis, but it has its drawbacks. First, it facilitates one-way traffic — in the morning traffic flows from Behala and in the evening, towards Behala. Second, at its mouth is a railway level crossing. So, every time it shuts down for 15 to 30 minutes, traffic accumulates.

Another resident of Behala, septuagenarian Chhanda Choudhury, sums up the situation succinctly. She says, “Behala is now nearly cut off from the main city. From the looks of it, residents have to remain bound within Behala. If you have to study, go to a local school or college, find a job in the neighbourhood, shop here, eat here and die here. ”

Eight days before Durga Puja this year, the Tala Bridge failed the health test — something that checks the load-bearing capacity of a bridge. The bridge used to handle 10,000 goods vehicles, 1,500 buses, 10,000 small cars and countless bikes on a daily basis, according to information from the Calcutta Traffic Police Department at Lalbazar. And now experts have pronounced the death sentence on it.

Visit the area and you’ll realise the bridge is not an isolated entity. It is one of three bridges — the others are Belgachia and Chitpur. All of it seems to mimic the human gut with its tangle of jejunums and duodenums. If traffic through any one is impeded, there is an overload on some other part, ultimately leading to a systemic collapse.

“Currently, small cars and two-wheelers are allowed to crawl on it at a speed of not more than 10 kmph,” says Santosh Pandey, who is deputy commissioner of Calcutta Traffic Police. He adds how the complete closure would result in congestion on the other routes and impossible traffic snarls. He rattles off a litany of specifics — how the cars and buses will have to be diverted from Chiriamore via Dum Dum Road, Seven Tanks, Paikpara, Raja Manindra Road, R.G. Kar to Shyambazar; how the goods vehicles will have to take the Second Hooghly Bridge and so on. “The pressure on the Dum Dum Road and the Belgachia Bridge would be too much to handle,” he says.

What is it that ails Calcutta’s bridges? In a word — negligence. According to experts, they have come to this sorry and dangerous pass due to lack of maintenance by successive state governments. “In fact, the newer bridges are in a far worse shape than the older ones,” says Ghoshal of CEAI. He adds, “The older ones had more of iron-based construction.”

To date, the bridges that have kept to the health check schedule are Aurobindo Setu, the Sealdah, Chingrighata, Kalighat, Gariahat, Chetla, Durgapur, Santoshpur and Dhakuria bridges, and Jibananda Setu. (During the load-bearing test a bridge closes for three days.) These bridges are crucial for traffic movement and without them Calcutta would be a grouping of small islands cut off from each other.

Vikram Singh’s office is in the Ruby Hospital vicinity. He has to travel from Behala for almost two hours every day. Says the 40-year-old, “For the past one year I have been taking the Bailey bridge. I often opt for Hyde Road too. One side of the journey takes one-and-a-half hours. Earlier it used to take me barely 40 minutes.” The pressure of traffic is such that Hyde Road has developed cracks.

Says Ashok Sengupta, former journalist and writer of the book Calcutta Connects, “In Germany, there is not just one bridge on one river. There are half a dozen of them; so when one bridge is closed for maintenance the others can serve the people. Of course, their population is nowhere close to our numbers.”

Private car owners are not the only ones to bear the brunt. Tapan Banerjee, who is general secretary of the Joint Council of Bus Syndicate, explains the repercussions of the closure of the Majerhat Bridge, which not only connected Behala with the rest of the city, but was also the link between the city and the south Bengal suburbs — Namkhana, Kakdwip, Sirakhol, Raichak, Raipur, Diamond Harbour, Pailan, Joka, Behala and Budge Budge. There were 42 bus routes that ran through this bridge. Now, all the buses have been diverted. Citing two altered routes, Banerjee says, “Both are seven to eight kilometres longer. We have to bear double the loss — extra petrol, extra time, lesser trips and lower profits.”

The Telegraph

As for the Tala Bridge, there are 24 bus routes between Barrackpore and Dharmatala that run through it. “Now, when they are changing the route via Sinthi More and Chiriamore, the number of passengers is getting divided between the existing buses and the alternative ones. This is fostering an unhealthy competition between bus and bus, which manifests in speeding — which in turn threatens passenger safety,” says Banerjee.

The condition of the bridges in the city and the aftermath of their closure are unnerving. “Even the three to four days closure for health checkup of the bridges throws traffic out of control. What will happen if they close down forever?” asks Sujoy Das, a cabbie. He recalls the time when the Jibananda Setu was closed for repair and the traffic would seep into the lanes running through Dhakuria and Selimpur area. He says, “Passengers would cancel trips as the wait time was well over 45 minutes.” Jodhpur Boys’ School remained shut for the entire period of repair.

All this could have been avoided if regular checks and periodic maintenance had happened, says Ghoshal. “The Howrah Bridge is 75 years old; the Bally Bridge is soon going to turn 100. These constructions have been maintained by the railways and they are in good health. But it is the newer ones that are crumbling,” he says.

Ghoshal continues, “While constructing a bridge, there are several things that have to be considered — its load-bearing capacity, the nature of daily traffic, how wide it has to be, the height from the ground or water level, the distance between pillars and so on.”

But most importantly, the land in and around a bridge has to be kept clear for maintenance work and for construction of alternative routes, if and when required. He cites the example of the area under as well as adjoining the Bijon Setu, which has been sold off to realtors. Lots of residential as well as commercial structures have come up there. “You cannot ask them to vacate. There is a registered industry under the Aurobindo Setu too. The Sealdah Bridge has the thriving Sisir Market below it. There are over 300 shops there. How can a bridge be maintained under these circumstances,” he asks exasperatedly.

The rhyme about London Bridge is composed as a series of suggestions and exhortations to a “My fair Lady”. It wraps up with the idea that while using sterling material she must hire a watchman to keep vigil.

Please note.