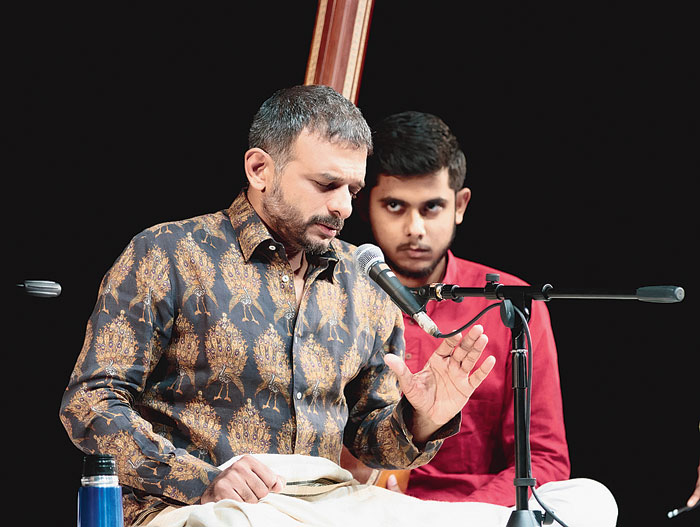

Introducing raga Bhairavi, the formidable classical Carnatic singer T.M. Krishna tries to explain the idea of singing a raga. It is a search.

As he sings the notes, he seems to implore the spirit of the raga to appear. It also seems, at least to this uninitiated listener, that what he is seeking is not a disembodied spirit, but one with a distinct, beautiful form. The word genius comes to mind, but this spirit is the raga itself. The music mesmerises.

Yes, there is magic in music, Krishna agrees. It is a rainy Saturday evening, end-August. He is addressing a large hall bursting at all sides at Experimenter Outpost, an itinerant art hub created by Experimenter, a leading gallery in Calcutta, at a beautiful old house on Ballygunge Circular Road. The house, chosen for the event, had begun to look forlorn, but it glows with lights as Krishna, a Magsaysay award winner who is also a fierce advocate of free speech and dissent and a luminous presence himself, climbs on to the stage to deliver his lecture-demonstration Manodharma.

The event is being held to celebrate the 10th anniversary of Experimenter, which shows contemporary art. The backdrop is unusual; the large ground-floor space reclaimed for Krishna is also home to an art exhibition that imitates a nervous system on an industrial scale.

There is magic, Krishna continues, in music, but it does not happen every day. It happens when there is emotion, when there is creativity. The notes are not a rigid structure: they allow the freedom to explore. The creative also implies the ethical.

Krishna, who lives in Chennai, conceived Manodharma as a lecture series. “Manodharma,” he says, “is an exploration of the ethical within one’s being.” It is a combination word born of manas (literally, mind), and dharma. It is an instrument of critical inquiry, also of music.

Early in his career as a musician, he began to feel bothered by a certain aspect of the music he was practising. He began to question why Carnatic classical should be the preserve of the Brahmins.

At Jadavpur University (JU) the previous evening, on the first day of his three-day Calcutta visit, Krishna had spoken about this disenchantment. “I was already a star,” he said. But uncomfortable about Carnatic classical being a preserve of caste.

Later in an email interview he explains clearly why. “As I explored the musical history of the form — and I am speaking of the technical detailing, melodic, textual and rhythmic intricacies and their histories, I realised that none of these aspects of an art form can be divorced from the social, philosophical and political constructs that govern every interior musical movement,” he says. “This realisation made me enquire into caste, gender and community.”

Art can clearly not be divorced from the social, the ethical, the political — and Carnatic classical is not the only form of music that is restricted by caste or gender, and it is not the only form that does not want to reflect on itself.

“I want to say this, Hindustani music has as many socio-political issues as its southern counterpart, but no one within its community is willing to openly discuss it,” he writes.

But then he not only wants to free music from the clutches of caste, he wants to collapse the distinction between genres, questioning the politics of even the nomenclature. What is Hindustani, he asks. There is no Hindustani — “only dhrupad and khayal.”

“No musical movement is apolitical or non-political and hence if we believe in democratic and ethical living, this has to be sought within art,” he says in the interview.

“There is something called ethical art and that comes from working through the cobwebs of socio-political pressures, power and oppression. Art exists within oppressive structures and it exists within art forms and between art forms,” he writes.

But for Krishna it is not enough to identify those oppressive structures. He had to make an attempt to free the art. Gnosis must meet praxis. Music must be revisited — and reformed.

So he has taken classical music to the unlikeliest of places, literally. One example is his Poromboke song. In it he sings powerfully and movingly at the most unremarkable places in Chennai, to draw attention to “development” threatening to swallow a wetland.

Poromboke is actually a movement that Krishna has embraced. The Tamil word represents all unbuilt public open spaces, spaces that tend to remain invisible till a highrise or a mall comes up there. But with Krishna, and his colleague, the environmentalist Nityanand Jayaraman, the word has become a metaphor for almost everything that is marginalised and neglected: spaces, peoples, music.

Krishna and Jayaraman participate in an art festival hosted by a fishing village in Chennai where classical music is performed with other kinds of music, on the same platform.

But there we go again! Language and culture conspire in such a way to maintain social hierarchies that to talk about this experiment is to talk about “other” forms of music against the “classical”, though Krishna at the very moment is questioning definitions such as “classical”, or “folk”.

But can music be equal?

Krishna himself admits problem areas. Answering a question at JU, speaks of his experience of performing with the Jogappas, a transgender community. But he remained the centre of attraction. He had to perform with them to get them the visibility. The exchange was not equal. It is not easy to reform a music.

Besides, is it right to look at Carnatic classical as only discriminatory?

In a newspaper article G. Pramod Menon says the problem about Carnatic music is not so much that it is Brahminical, but that it is so demanding that it has remained within a community, like many other skills such as carpentry. But if Carnatic music is “demolished and reconstructed according to (Krishna’s) vision, will it still remain Carnatic music?” Menon asks.

The audience at the Kala Mandir concert, Krishna’s last performance in the city, however, blissfully forgot all the charges the musician has levelled against his music. Listening to him was “magical”, said an overwhelmed member of the audience.