A family puja that was once upon a time graced by the presence, and active hand of one of Bengal’s most renowned writers, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, continues at Panitar village in North 24 Parganas’ Basirhat, in the devoted, but understated, fashion in which the author intended.

The story of how the 1894-born Bandyopadhyay — who toiled for years as a teacher and a secretary before his 1928 breakthrough work Pather Panchali — nurtured his sensibility as a portrayer of the Bengali working class is reflected in the story of the family puja at his in-laws’ ancestral home in Panitar.

“Bandyopadhyay got married to Gouri Devi in 1917 but before that, he had known her father Kaliprasanna Mukherjee, who was a lawyer at Basirhat court, for long,” said Bankim Mukherjee, a nephew of Gouri Devi who runs a diagnostic centre in Basirhat.

“The family puja at the Mukherjees’ home played a vital role in Bandyopadhyay’s personal life as well as in his view of rural Bengal. He was the first person outside the family who Kaliprasanna invited to organise the annual Puja,” added Mukherjee.

Elderly residents of Panitar, as well as descendants of the Mukherjee family, recall ancestral pujas of the early 20th century as being shrouded in orthodoxy. In that milieu, following his marriage to Gouri Devi and after years of acquaintance with her father, Bandyopadhyay threw open the Mukherjee puja to the poor and downtrodden from the surrounding village areas.

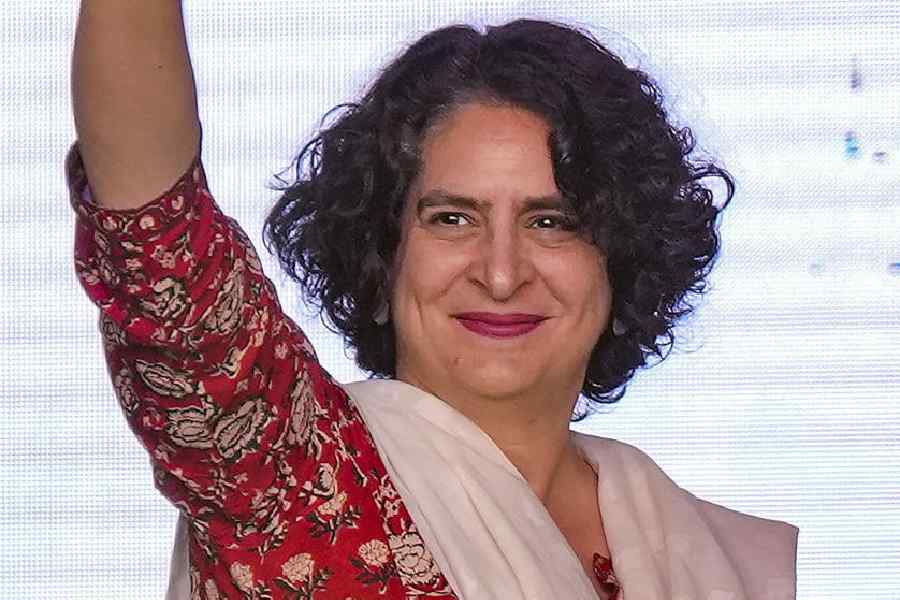

A bust of Bandyopadhyay Picture by Pashupati Das

“Pujas were a rich person’s affair in those days, so not everyone was invited. But Bandyopadhyay made an exception to the Mukherjee family’s puja because he could not separate his compassion for the downtrodden from his desire to share this annual celebration with others,” said an elderly resident of Panitar.

“Kaliprasanna allowed Bandyopadhyay this active hand in his own home because he saw the author’s budding talent. His ability to write and his ability to mingle with the world were not separate. He would get his hands into the most minute details of the puja, including distributing prasad himself to every visitor,” added Mukherjee.

Though Gouri Devi died an untimely death in 1919, Bandyopadhyay continued his association with the puja for a few more years before he moved away to Ghatshila in present-day Jharkhand.

Academics agree that while the next two decades were marked by deep grief for him associated with the death of his wife, they also ushered in his seminal literary oeuvre including Pather Panchali (1929).

Bandhopadhyay’s second marriage was nearly two decades later, in 1946, four years before his own untimely death from a heart attack in 1950.

Although the venue of the Mukherjee family puja has changed — following their decision to donate their ancestor Kaliprasanna’s home to the state government for preservation a few years ago — residents of Panitar, and visitors from far and wide, recall and respect the event for Bandyopadhyay’s famous benevolence.

“The second part of Bandyopadhyay’s life still remains largely untold. But it is quite natural for a person who penned pieces like Pather Panchali, Aranyank, Aparajito and Ichamati, depicting the life of the common people, to make such an open-hearted gesture.

He perhaps realised the isolation that the poor felt, and still feel, during festivals. And that is why he is still respected as the ‘people’s author’,” said Sukhen Biswas, head of the Bengali department at Kalyani University.