Last fall, a pair of historians revealed that yet another Soviet spy, code named Godsend, had infiltrated the Los Alamos laboratory in the US where the world’s first atomic bomb was built. But they were unable to discern the secrets he gave Moscow or the nature of his work.

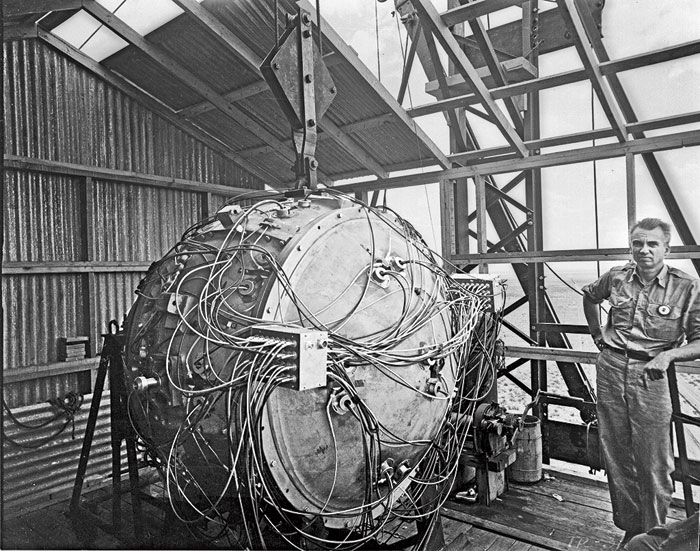

The world’s first atomic bomb, an implosion-type device nicknamed The Gadget, that had a similar firing circuit NYTNS

However, the lab recently declassified and released documents detailing the spy’s highly specialised employment and likely atomic thefts, potentially recasting a mundane espionage case as one of history’s most damaging.

It turns out that the spy, whose real name was Oscar Seborer, had an intimate understanding of the bomb’s inner workings. His knowledge most likely surpassed that of the three previously known Soviet spies at Los Alamos, and played a crucial role in Moscow’s ability to quickly replicate the complex device. In 1949, four years after the Americans tested the bomb, the Soviets detonated a knockoff, abruptly ending Washington’s monopoly on nuclear weapons.

“It’s fascinating,” Harvey Klehr, an author of the original paper, said in an interview. “We had no idea he was that important.”

The documents from Los Alamos show that Seborer helped devise the bomb’s explosive trigger — in particular, the firing circuits for its detonators. The successful development of the daunting technology let Los Alamos significantly reduce the amount of costly fuel needed for atomic bombs and began a long trend of weapon miniaturisation. The technology dominated the nuclear age, especially the design of small, lightweight missile warheads of enormous power.

Seborer’s inner knowledge stands in contrast to the known espionage. The first Los Alamos spy gave the Soviets a bomb overview. So did the second and third.

The new clues suggest that Seborer’s thievery “could have been unique,” Alex Wellerstein, a nuclear historian at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, US, said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean it was — just that it could have been.”

A furtive boast

Klehr, an emeritus professor of politics and history at Emory University, US, said the new information cast light on a furtive boast about the crime. Last fall, in the scholarly paper, the two historians noted that Seborer fled the US in 1951 and defected to the Soviet bloc with his older brother Stuart, his brother’s wife and his mother-in-law.

The paper also noted that an FBI informant learned that a communist acquaintance of the Seborers eventually visited them. The family lived in Moscow and had assumed the surname Smith. The visitor reported back that Oscar and Stuart had said they would be executed for “what they did” if the brothers ever returned to the US.

In a recent interview, Klehr said he originally thought the spies were exaggerating their importance. But, he added, the new information on Oscar’s technical knowledge suggested otherwise, although Stuart’s exact role in the spy case remains unclear. “Maybe it wasn’t hyperbole,” Klehr said.

I spy: Oscar Seborer NYTNS

Last fall, the historians described the Seborers as a Jewish family from Poland that, in New York, became “part of a network of people connected to Soviet intelligence.” Both Oscar and Stuart attended City College, “a hotbed of communist activism,” the historians wrote.

Stuart took a maths class there in 1934 with Julius Rosenberg, they reported. In a notorious Cold War spy case, Rosenberg and his wife, Ethel, were convicted of giving the Soviets atomic secrets. In 1953 they were executed at Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York, orphaning their two sons, ages 6 and 10.

The scholarly paper, written with John Earl Haynes, a former historian at the US Library of Congress, appeared in the September issue of Studies in Intelligence. The journal, a CIA quarterly, is published for the nation’s intelligence agencies as well as academic and independent scholars.

‘Unbelievably complicated’

All three previously known Los Alamos spies told the Soviets of a secret bomb-detonation method known as implosion. The technique produced a bomb far more sophisticated than the crude one dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. A prototype of the implosion device was tested successfully in the New Mexican desert in July 1945, and a bomb of similar design was dropped on Nagasaki weeks later, on August 9. Four years later, the Soviets successfully tested an implosion device.

The early bombs relied on two kinds of metallic fuel, uranium and plutonium. The bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima worked by firing one cylinder of uranium fuel into a second one, to form a critical mass. Atoms then split apart in furious chain reactions, releasing huge bursts of energy.

In contrast, the implosion bomb started with a ball of plutonium surrounded by a large sphere of conventional explosives. By design, their detonation produced waves of pressure that were highly focused and concentrated. The waves crushed inward with such gargantuan force that the dense ball of plutonium metal was compressed into a much denser state, triggering the atomic blast.

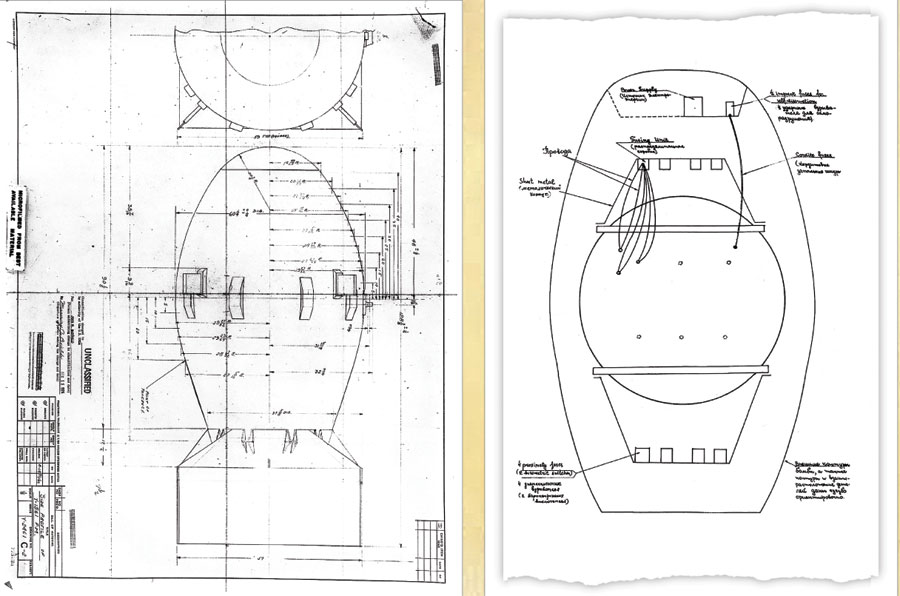

The new documents show that Seborer worked at the heart of the implosion effort. The unit that employed him, known as X-5, devised the firing circuits for the bomb’s 32 detonators, which ringed the device. To lessen the odds of electrical failures, each detonator was fitted with not just one but two firing cables, bringing the total to 64. Each conveyed a stiff jolt of electricity.

Glen McDuff, a Los Alamos scientist, once characterised the bomb’s firing circuits as “unbelievably complicated”. A major challenge for the wartime designers was that the 32 firings had to be nearly simultaneous. If not, the crushing wave of spherical compression would be uneven and the bomb a dud. According to an official Los Alamos history, the designers learned belatedly of the need for a high “degree of simultaneity”.

Possible clues of Seborer’s espionage lurk in declassified Russian archives, Wellerstein of the Stevens Institute of Technology said in an interview. The documents show that Soviet scientists “spent a lot of time looking into the detonator-circuitry issue,” he said, and include a firing-circuit diagramme that appears to have derived from spying.

Keeping it quiet

If the 1956 documents shed light on Seborer’s crime, they do little to explain why the US kept the nature of his job and likely espionage secret for 64 years.

One possibility was domestic politics. Several atomic spy scandals shook the nation in the early 1950s, starting with the arrest of the first Los Alamos spy. His testimony led to the capture of the second, and to the execution of the Rosenbergs. The anti-Communist hysteria of the McCarthy era reached a fever pitch between 1950 and 1954. President Dwight Eisenhower, who had put himself above the fray, began to fight back with information leaks and administrative fiats.

Klehr of Emory said it was late 1955 when the FBI first uncovered firm evidence that Seborer had been a Soviet spy, prompting the inquiry that led to the Los Alamos correspondence of September 1956. A presidential campaign was then underway, and the last thing Eisenhower needed was another spy scandal. The same held true in 1960, when Eisenhower’s vice-president, Richard Nixon, fought John F. Kennedy for the White House.

“It’s entirely possible — let sleeping dogs lie,” said Klehr. “But you can’t prove it.”

A more likely reason for the silence, he added, was the flimsy nature of the evidence against Seborer. Nothing in publicly released FBI files suggests that warrants had been obtained for wiretaps, a legal requirement. Nor did the bureau know the identity of the courier between Seborer and his Soviet controllers. Finally, the two prime suspects were in Russia, out of reach. It was doubtful that the lawmen “could even get an indictment,” Klehr said.

He noted, too, that much of the information the FBI had about the Seborers had come from a hugely successful undercover operation known as Solo, which had infiltrated the US Communist Party in the 1950s and continued the monitoring as late as 1977. Most likely, the bureau wanted to do nothing that might risk revealing the identities of its informants.