English naturalist Charles Robert Darwin’s seminal book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection went to press in 1859. That was 40 years before the “concept of viruses” was introduced to the world of science by Russian botanist Dmitri Ivanovsk. It took another century for viral researchers to decipher the genetic make-up of these “infectious agents”, to find out how they replicate and spread disease.

Darwin — shunned and ridiculed after the publication of his book — would probably be amazed to know that viruses such as the Covid-19 are considered living evidence of his theory of evolution.

“If Charles Darwin reappeared today, he might be surprised to learn that humans are descended from viruses as well as from apes,” British microbiologist Robin Weiss wrote in the journal Retrovirology. He was referring to fragments of retroviruses — close cousins of the coronavirus — found in the human genome.

These fragments are the fossils of a number of ‘‘killer viruses’’, including several novel reassortments of influenza or coronaviruses that ravaged humans on a large scale in the past. These so-called endogeneous retroviruses (ERVs) are actually trophies of ancient molecular battles between viruses and their human hosts — one which the humans eventually won. “Some 8 per cent of human DNA represents fossil retroviral genomes,” pointed out Weiss in his seminal research paper in 2010.

When competing groups of scientists in different parts of the world fully mapped the human genome in 2003, they found something they had never anticipated: bits that have no known function. Many scientists termed these seemingly inert shards “junk DNA” that littered our bodies. In the following decade, however, geneticists realised that some of those bits were actually endogenous retroviruses, fossils of defeated viruses that managed to invade our bodies but were disabled by our immune system. In Darwinian terms, in the “struggle for existence” our immune system got better of them and there was “survival of the fittest” through “natural selection”. Instead of getting buried as mineralised relics, these viruses reside within our DNA as bits of genetic code carrying records of millions of years but forever disabled, with no power to make us sick.

The discovery of the human genome as a living document of ancient and now extinct viruses prompted the emergence of a new field called palaeovirology. Two of its proponents, Michael Emerman and Harmit S. Malik, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, US, define palaeovirology as the study of extinct viruses (called palaeoviruses) and the effects these agents have had on the evolution of their hosts. In other words, indirect evidence of these viral fossils can help reconstruct the past and offer clues on how to fight emerging viral epidemics or pandemics.

Malik grew up in Bombay and studied chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology there. He studies evolving proteins and “the genetics of evolutionary conflict embedded in the molecules”, which has helped him uncover “previously unrecognised sources of conflict”.

As a pioneer palaeovirologist, Malik is fascinated by the constant battle being waged between humans and viruses for hundreds of thousands of years. In the course of his study, he found telltale imprints in our genome that narrate the story of how viruses infected our cells, how sometimes we have fought back by changing our protein and how sometimes viruses evaded them to get an upper hand. This evolutionary cat-and-mouse game has shaped our defence against viruses.

Palaeovirologists have also studied how similar viruses have attacked our close relatives, the primates — chimpanzees and gorillas — and compared how we have fared in these battles. For instance, the virus that leads to to the killer disease Aids in humans does not have much of an effect on chimps. What makes chimps relatively immune to this scary virus? Malik and Emerman found the clue to this mystery in an endogenous retrovirus called Pterv found in chimps (and other apes) but not in humans. They surmised that the retrovirus may have infected both humans and chimps about 4 million years ago. We learnt to stave off the virus while the chimps were hit by an epidemic. A gene called Trim 5 alpha is believed to have helped humans make a protein to purge the virus.

Malik and his colleagues reconstructed a part of the Pterv through computer modelling and found that while Trim 5 alpha helped us prevent the entry of the virus, it made us vulnerable to the HIV virus that causes Aids. However, the monkey version of the gene helps protect the apes from HIV and Aids. They concluded that if we can develop a therapy based on the Trim 5 alpha protein, it could defeat HIV. Research on drugs based on such evolutionary principles, however, is few and far between

Scientists have been studying several resurrected palaeoviruses like Pterv through evolution-guided reconstruction procedures. In 2005, researchers at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reconstructed the influenza virus that caused the 1918-19 flu pandemic, which killed as many as 50 million people worldwide. According to CDC, the research provides new information about the properties that contributed to its exceptional virulence. “The natural emergence of another pandemic virus is considered highly likely by many experts, and therefore insights into pathogenic mechanisms can and are contributing to the development of prophylactic and therapeutic interventions needed to prepare for future pandemic viruses,” says a CDC release.

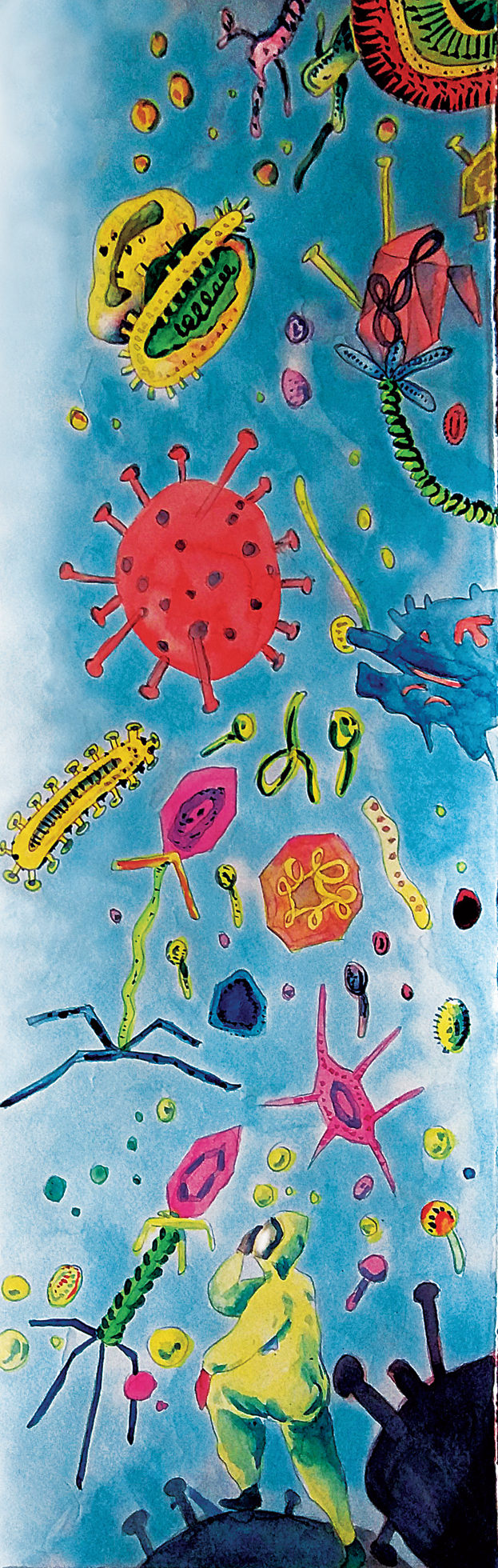

The rapid evolution of viruses and emergence of the new coronavirus Covid-19 has once again shown that viruses evolve by the same means as humans. Many of these viruses hop from animals to humans and evolve, swapping genetic material in and out of respective genomes. That’s why we can have immunity to a virus we’ve had in the past, but get seriously affected by one our body has never seen before.

Somewhere, Darwin must be feeling vindicated that his theory is so starkly exposed in a viral machinery.