Sitting in his limousine, the Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, rolled out a 32-second-long video message on Twitter on June 10. He said in Bahasa, “Let’s join hands, unite, and put our mind and energy to build a developed Indonesia.”

Ever since Widodo got re-elected for a second term last month, his focus has been on development. But soon after his re-election, he faced disruptions. As the final election results were declared, riots broke out in the capital city of Jakarta for over two days, killing eight people and injuring seven hundred others. Early reports suggest that apart from a group of paid thugs, members of the militant Islamist group, Front Pemuda Islam, attacked the police with rocks and petrol bombs.

Interestingly, these hardline Islamists supported Jokowi’s opponent, the former army commander, Prabowo Subianto. The grand imam of FPI, Habib Rizieq Shihab, addressed his election rally from Saudi Arabia via video call. Analysts call Prabowo and Shihab ‘bedfellows’, united by a common enemy — Widodo.

Widodo’s win could create trouble for the FPI. Its status as a legally registered social organization expires today, and there are chances that its appeal for re-registration would be rejected. Public pressure is mounting on authorities to do so. A petition called ‘Stop the Permit of FPI’, filed by Ira Bisyir at Change.org, has received over 4,81,665 signatures so far.

In this last term, analysts say that Widodo would give a fresh push to his liberal and progressive image, which was largely compromised earlier. In his previous term, the “hard-metal-loving secularist” failed to protect free speech, the rights of religious and ethnic minorities and those of LGBTs. But Indonesians still pinned their hopes on him. They preferred to choose a ‘moderate’ Widodo, representative of ‘pluralist’ Indonesia, over a ‘conservative’ Subianto, representative of a ‘hardline Islamist’ Indonesia. Clearly, this is a positive shift from the faith-based politics, which is thriving elsewhere.

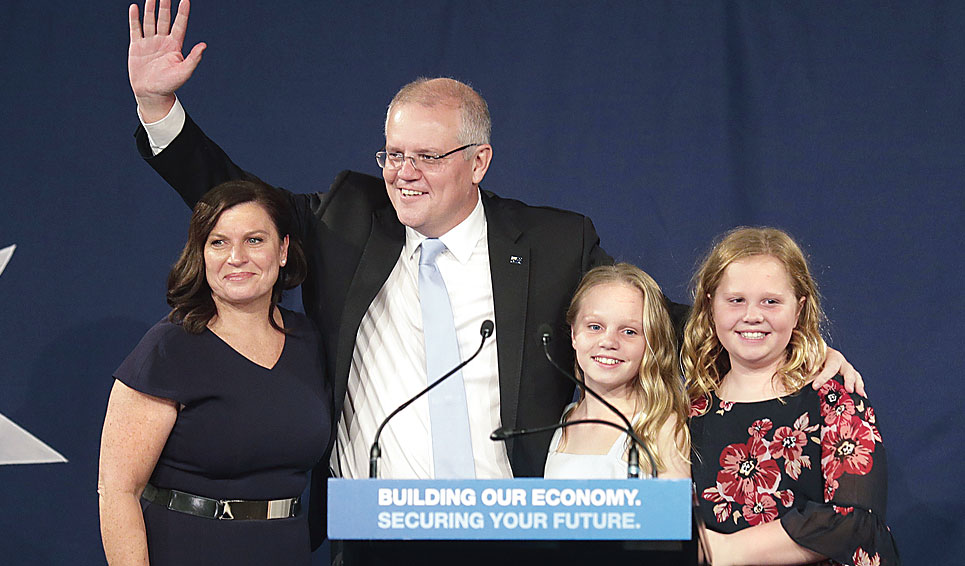

For example, across the Indian Ocean, Australia, a country whose politics has long been secular, recently re-elected the 51-year-old conservative, Scott Morrison, as prime minister. In 2008, while he was delivering his maiden speech in Parliament, he said that he derived the values of loving-kindness, justice and righteousness from his ‘faith’. While quoting the American senator, Joe Lieberman, who had said, “the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, not from religion,” Morrison asserted at the same event, “I believe the same is true in this country.” In April this year, Morrison, who holds regressive views on immigration and same-sex marriage, invited television cameras to film his Easter Sunday service at a church.

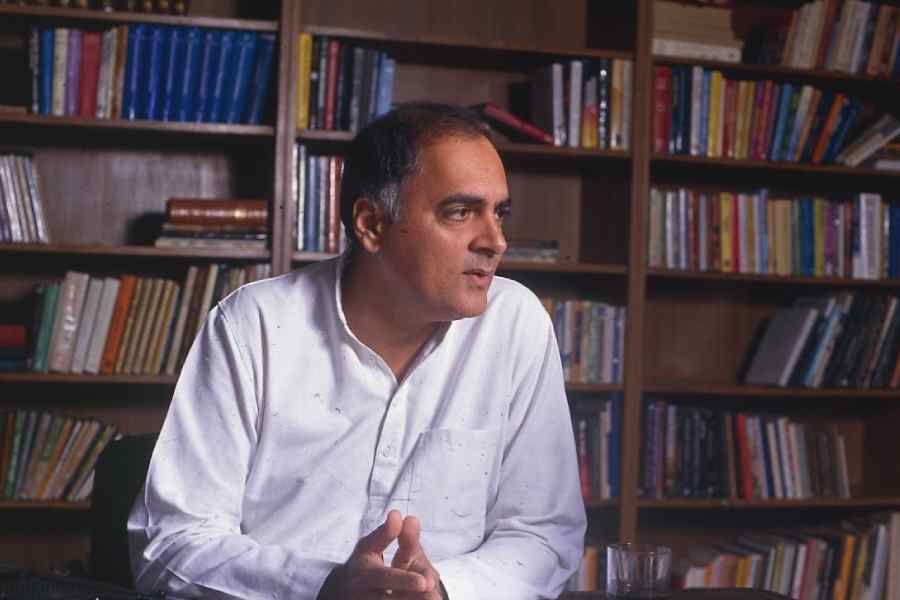

A similar trend is visible in India, which has re-elected the 68-year-old Hindu nationalist, Narendra Modi. Like Morrison, Modi loves to wear his religion on his sleeve. A day before the last phase of the general election, Modi invited television cameras to film him meditating inside a cave near the Kedarnath shrine. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, which rose to power by playing divisive faith-based politics, won 303 seats in Parliament. On the day of his victory, Modi had tweeted, “India wins yet again.” Perhaps he was referring to the India that has lapped up his politics of religious identity and Hindu majoritarianism.

Faith-based politics has played a leading role in the politics of neighbouring Bangladesh too. Bangladesh re-elected Sheikh Hasina Wajed last year. Wajed, a ‘secular’ leader, has been wooing the radical Islamist group, Hefazat-e-Islam, for many years. She introduced religious education in government schools, edited out poems and stories that conservative Islamists deemed atheistic and also recognized the Qawmi Madrasa degrees. In return, the Islamist group’s head, Shah Ahmed Shafi, bestowed the honorific, ‘Qawmi Janani (mother of the qaum)’, upon Wajed. Like Wajed, who hobnobbed with the Islamists to garner the support of the large Qawmi Madrasa populace, Widodo chose the conservative cleric, Ma’ruf Amin, as his running mate to strengthen his candidacy’s Islamic credentials.

Now that Widodo has been re-elected, questions have been raised regarding his present term by his constituents who gave him a second chance. He has stressed upon development and democracy, but will he abjure faith-based politics? Will he revive the vanishing, tolerant Indonesian Islam? How is he going to do all this with Amin — he issued a fatwa opposing religious pluralism, liberalism and secularism — as vice-president?

But what if Widodo adopts the political strategy of the leaders in his neighbourhood? What if he becomes like Morrison, someone who doesn’t like being labelled a ‘fundamentalist’ but has reservations about gay rights? Or like Wajed, who calls herself ‘secular’ but appeases religious extremists? Or, perhaps, like Modi, who talks of ‘inclusive’ India but doesn’t bat an eyelid when minorities get lynched on the streets?