A famous Bengali restaurant in the city serves excellent food. The staff greet you warmly. The portions are generous. The menu is diverse. Only one problem persists: the music is Tagore on guitar. Always.

A dear friend and I find it a little disconcerting during every meal. The guitar versions, usually of the most popular of Tagore’s songs, produce a curious effect on those familiar with them. The guitar is not strictly faithful to the original tunes. What we get usually are thick spurts of sound floating on a thin soup of music that seems vaguely familiar. As we recognize the tune, the words begin to surface in our minds, and then we realize to our horror that the song being played is “Je raate mor duarguli bhanglo jhode... (The night my doors were broken open by the storm...)”. The rest of the original is a celebration of the dark, fierce storm as a herald of the great spirit that animates Life itself — and so much of Tagore’s work. A touch of Shelley there, too.

It is hardly something that you can digest as you are digging into prawns cooked inside a large, green, tender coconut. One evening, my friend, an upholder of impeccable standards, both by maintaining and demanding them, decided to take matters into his own hands.

My friend insists that we do not get the highest standards because we do not want them. What are we afraid of?

I am afraid. Of causing disruption. My friend is not. So I was slightly panicking as he went up to speak to the manager, who is a friendly, well-mannered young man with an open, smiling face. “Why,” my friend demanded straightaway, “do we have to listen to this music always?”

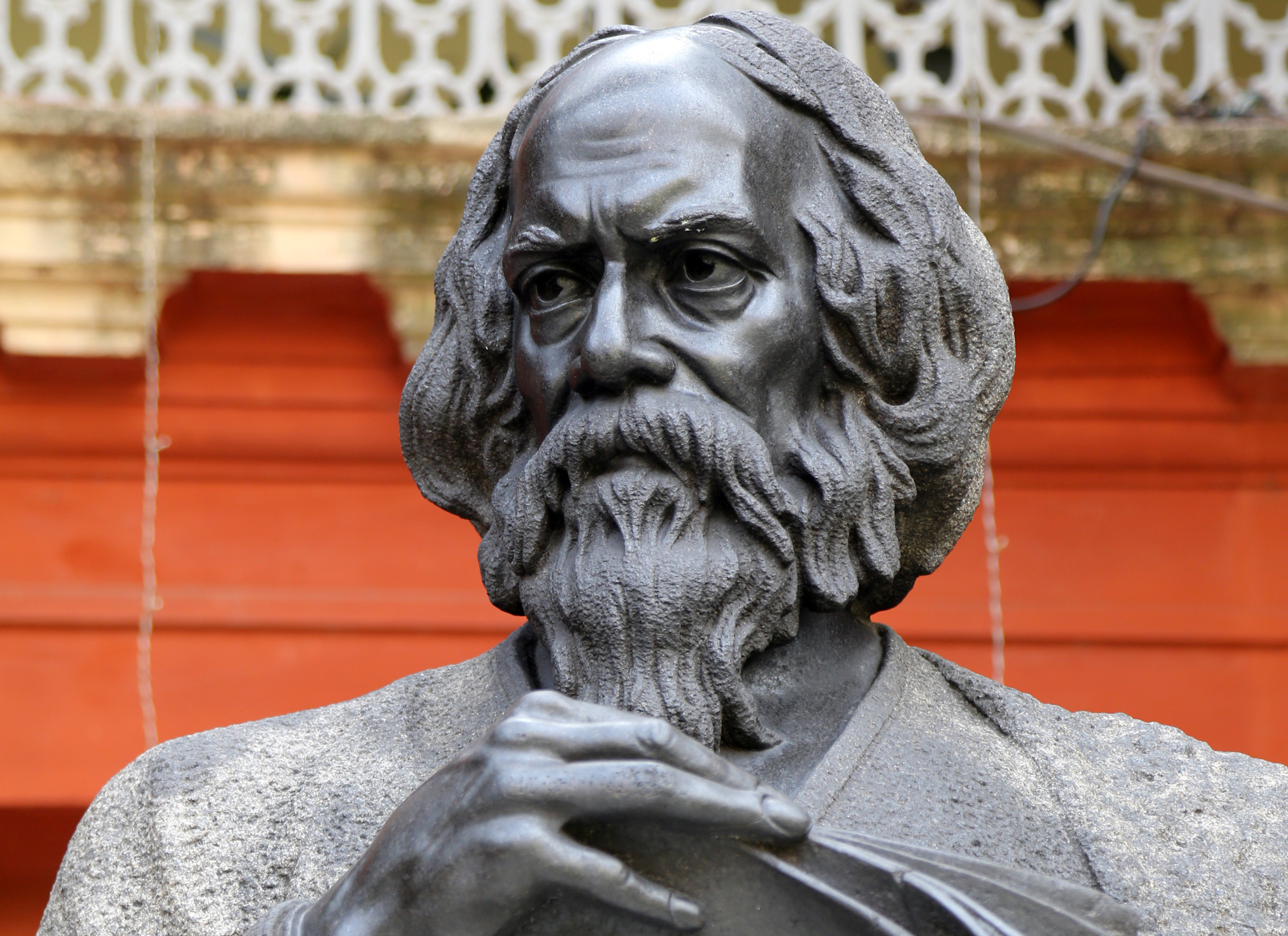

The manager was stunned. “What’s wrong with it, sir?” he asked. “Well, it is Rabindrasangeet on guitar. The guitar is very bad. And is it right to play ‘Je raate mor duarguli...’ at a restaurant?”

The manager had never heard such a complaint before. He said that the Rabindrasangeet was meant to blend in with the flavours of the restaurant.

This incensed my friend. “Why do we have to play Bengali music in a Bengali food restaurant always? Do south Indian restaurants only play south Indian music? Is Rabindrasangeet meant to blend in with food flavours?” he asked.

“You are right, sir,” said the manager, with no hint of irony.

“You can try light classical. You can play thumris. Bengal was once cosmopolitan, you know. Playing different kinds of music is also being Bengali, you know. Only playing Bengali music is actually provincial,” my friend continued.

“And sometimes you can play chamber music. Schubert. Mozart. Or jazz. Miles Davis,” he concluded.

I hated to look at my friend and the manager together. Between them a great gulf had opened up. Although both were speaking mostly English, it was a huge cultural divide, created not so much by anything else as by the 25 years or so that separated my friend from the manager. They were looking at each other with utter incomprehension across a changed world. At my friend’s end such a conversation was possible; at the manager’s end, not.

The manager was also at an obvious disadvantage. Used to looking at Rabindrasangeet as a part of the ambience, which he had assumed all his clients enjoyed, he could not process the cultural load of high art that had been dropped on him suddenly. Was he feeling slightly bullied?

At the same time, my friend looked so vulnerable. He was completely un-understood. Perched at his lofty height, he looked forlorn and his choices freakish. Why should a person who wants good music have to feel so alienated?

“Your tastes are very classical, sir,” said the manager, with genuine respect. “I will try and see what changes can be made immediately.”

We have been to the restaurant two or three times since the conversation. The guitar flowed unabated in the run-up to Noboborsho. The last time, our anxiety about the outcome of the impending elections made it worse.