Pushkar is a PhD in political science (McGill University) and currently director of The International Centre Goa, Dona Paula. The views expressed here are personal

Why is the government showing such keenness for India’s universities to recruit foreign faculty?

A large part of the answer to why the government has decided to liberalise the process of hiring foreign faculty is that it is promoting 20 universities – 10 public and 10 private institutions – as Institutions of Eminence (IoE). These eminent institutions are expected to compete with the best in the world and to break into the list of top 500 universities worldwide and if already there, to improve their rankings substantially. While only six institutions - the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) Bombay and Delhi among public institutions; and the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS) Pilani, Manipal Academy of Higher Education and Jio Institute among private institutions - were initially selected as eminent institutions, the government is likely to identify a few more such institutions in the coming months.

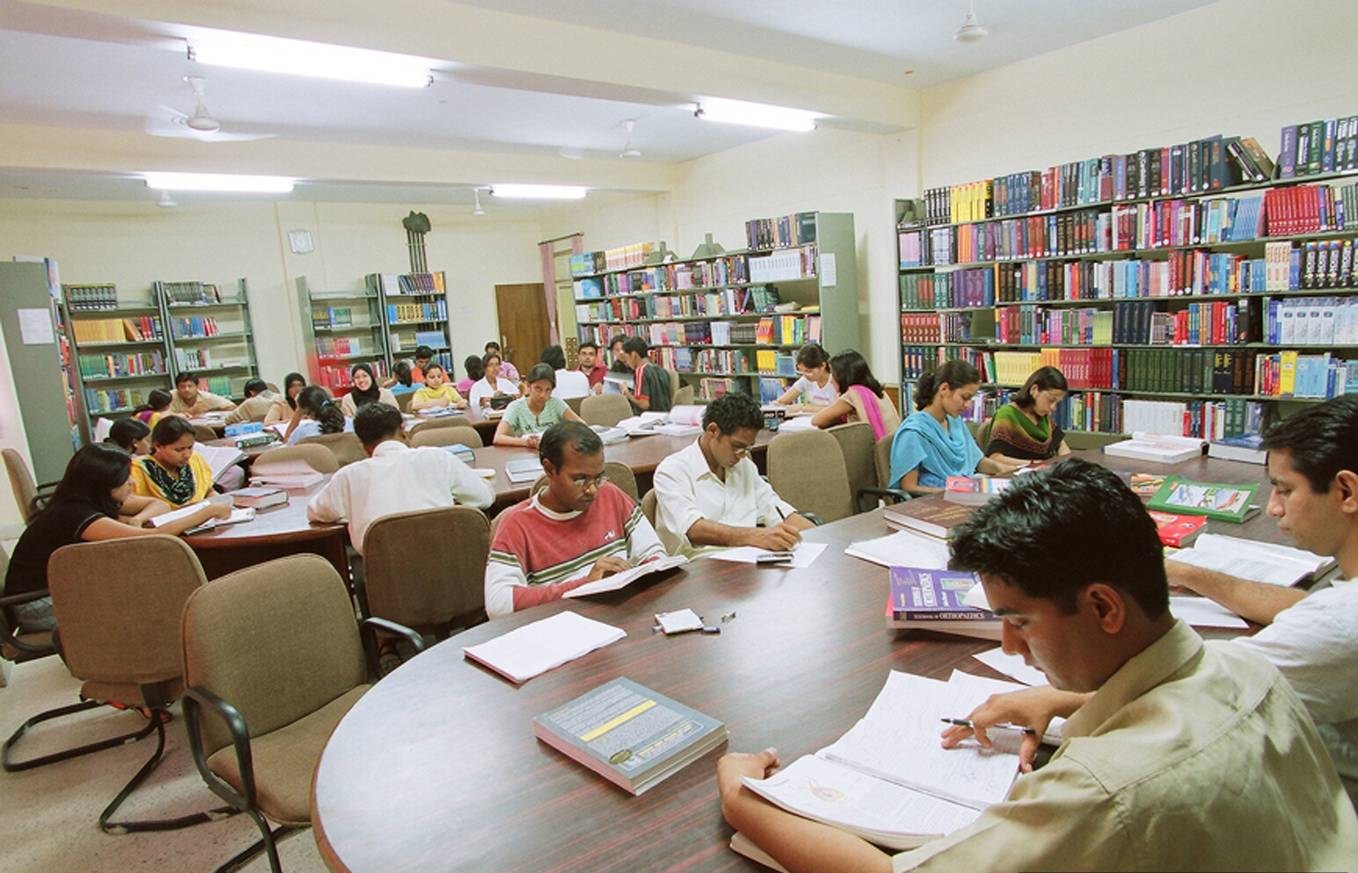

To compete effectively in world university rankings, other than improve their research output and the quality of research, both of which remain among the major weaknesses of India’s universities, the eminent institutions need to make advances on the internationalisation front as well. This requires them to hire larger numbers of foreign faculty, admit more foreign students, and for their faculty to do more and better collaborative research with faculty and researchers at foreign universities.

Foreign-trained faculty, whether foreigners or Indians, bring several advantages. It is usually (though not always) the case that those who earn their degrees from say the top 100-150 institutions in the world are better trained at the post-graduate level and, more importantly, tend to be more research-oriented. They typically publish more and in well-regarded journals and with reputed publishers, even if not everything they publish may be of high merit. Research output matters immensely in world university rankings and universities with larger numbers of faculty trained at the best institutions tend to outperform those with fewer such faculty. The advantage of foreign faculty is that institutions benefit both from their research output as well as from the extra points they score on the internationalisation dimension.

According to the guidelines for eminent institutions issued by the University Grants Commission (UGC), the selected institutions are permitted to hire up to 25% of its ‘faculty from outside India’. Curiously, however, while the guidelines recommend that institutions must recruit ‘a good proportion’ of foreign and foreign-qualified faculty, they also state that the definition of foreign/foreign-qualified faculty includes Indian nationals who have spent ‘considerable time in academics in a foreign country’. It is not clear why there is any merit in hiring larger numbers of Indians who may have spent ‘considerable time in academics in a foreign country’ unless that considerable time was spent in obtaining a PhD or for at least to gain international experience in the form of post-doctoral research. The UGC guidelines in their current form are rather vague. What will help Indian institutions improve in world rankings is not the considerable time that its faculty may have spent abroad, but whether more of its faculty earned PhDs from the best universities abroad, and whether good numbers of its faculty – up to 25% - are foreign passport holders.

Most Indian institutions are teaching focused and have no need for foreign faculty. However, the eminent institutions as well as those aspiring to compete on the world stage will benefit from hiring larger numbers of foreign-trained and foreign faculty. Doing so this will help them improve their research output as well as reward them on the internationalisation component in world university rankings.

In the early 2000s, the Indian School of Business (ISB), Hyderabad, which had just been set up, perhaps became the first Indian institution to actively recruit faculty trained at the best universities abroad, both foreigners and Indians. It did so in order to be able to, first of all, establish itself as a top-ranked Indian business school and second, to count among the best in the world. Today, ISB is often cited as an example of how world-class academic institutions can be built within a relatively short period of time, even in India.

The idea that foreign-trained faculty can play a significant role in ‘lifting’ an institution and improving the overall quality of education is well-accepted by Indian academics and government and university officials in private, even if grudgingly, but frowned upon and even rejected in public. Therefore, ISB’s success notwithstanding, it is only now that some of India’s academic institutions and more importantly the government has started to take greater interest in foreign-trained and foreign faculty.

Last month, the Indian government waived all prior security clearance requirements to hire foreign faculty. Universities can now hire foreigners directly without clearance from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). Mandatory clearance is now limited to foreigners from Prior Reference Category countries: Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, foreigners of Pakistani origin, stateless persons and those who wish to visit restricted areas. While some bureaucratic hurdles will remain, such as political clearance for foreign faculty, the intent behind the new rules is to reduce the process to three-four days so that universities and interested foreign faculty do not wait for long periods – often many months - before a decision is taken, by which time both sides lose interest. In addition, the government also decided that Overseas Citizens of India (who hold foreign passports) can be appointed as permanent faculty without the universities obtaining MHA or MEA clearance for them.