Seized, looted, bought unfairly, stolen, smuggled out. Countries once colonized in Asia and Africa have long sought to rediscover the histories carried by their own cultural objects displayed in museums in Western countries. Museums in the Netherlands have now decided to return thousands of objects taken away from Sri Lanka and Indonesia, while India, too, has a few items it would like the Dutch to return. Restitution of cultural assets is not a new demand. A French art historian said that calls for such repatriation had first gathered force at the end of the 1970s. At that time, Western museums had resisted strongly. Now, however, the Black Lives Matter movement has prompted a change in attitude. The widespread desire for a post-racist society required restitution of cultural riches as one of its steps.

The role of the Black Lives Matter movement in the fresh impetus to restitution is like a key that unlocks memories of all kinds of coercive power imbalances of the past — it functions like an image of colonialism. India has been asking for its objects back for years — especially from Britain. The United Kingdom, the United States of America and Australia have all been quick to return beautiful and valuable objects, antiques and images that they found to have been stolen and smuggled out of India in post-colonial times. But that is not the same as restoring objects looted by invaders or acquired by colonial rulers. In 2013, the British prime minister at the time, David Cameron, had said that he did not support “returnism” as that would empty British museums. He seemed unaware of the ironical light his comment threw on colonial practice.

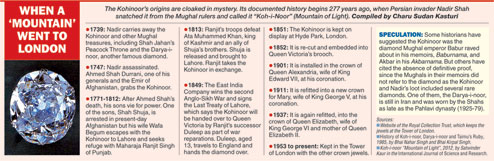

A former director of the Louvre, heading a French advisory commission on the return of cultural objects, said that the act would be one of solidarity and fairness. Certainly, repatriation would be a belated acknowledgement of the violence inhering in colonialism; it would also render hollow, by hindsight, the pretence of civilization’s ‘sweetness and light’ implied in the tranquil, labelled display of objects under glass in well-guarded museums. Satisfying the sense of rightness in, say, returning the Amaravati sculptures where they came from is indeed important, while it is also a further unravelling of the tangled skeins left behind by colonial rule, another step towards fathoming an experience that is both past yet never absent. That invasions, conquests, looting, colonial rule create restless histories of division and change that refuse to settle down — become absent — is best exemplified in the demand for restitution of the Kohinoor diamond addressed to Britain by not just India, but by Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan as well. Will the United Kingdom be able to decide between the two claimants for Tipu’s Wooden Tiger, India and Pakistan, should it be inclined to return it? The past never fails to haunt the human race; it only finds new ways of doing so.