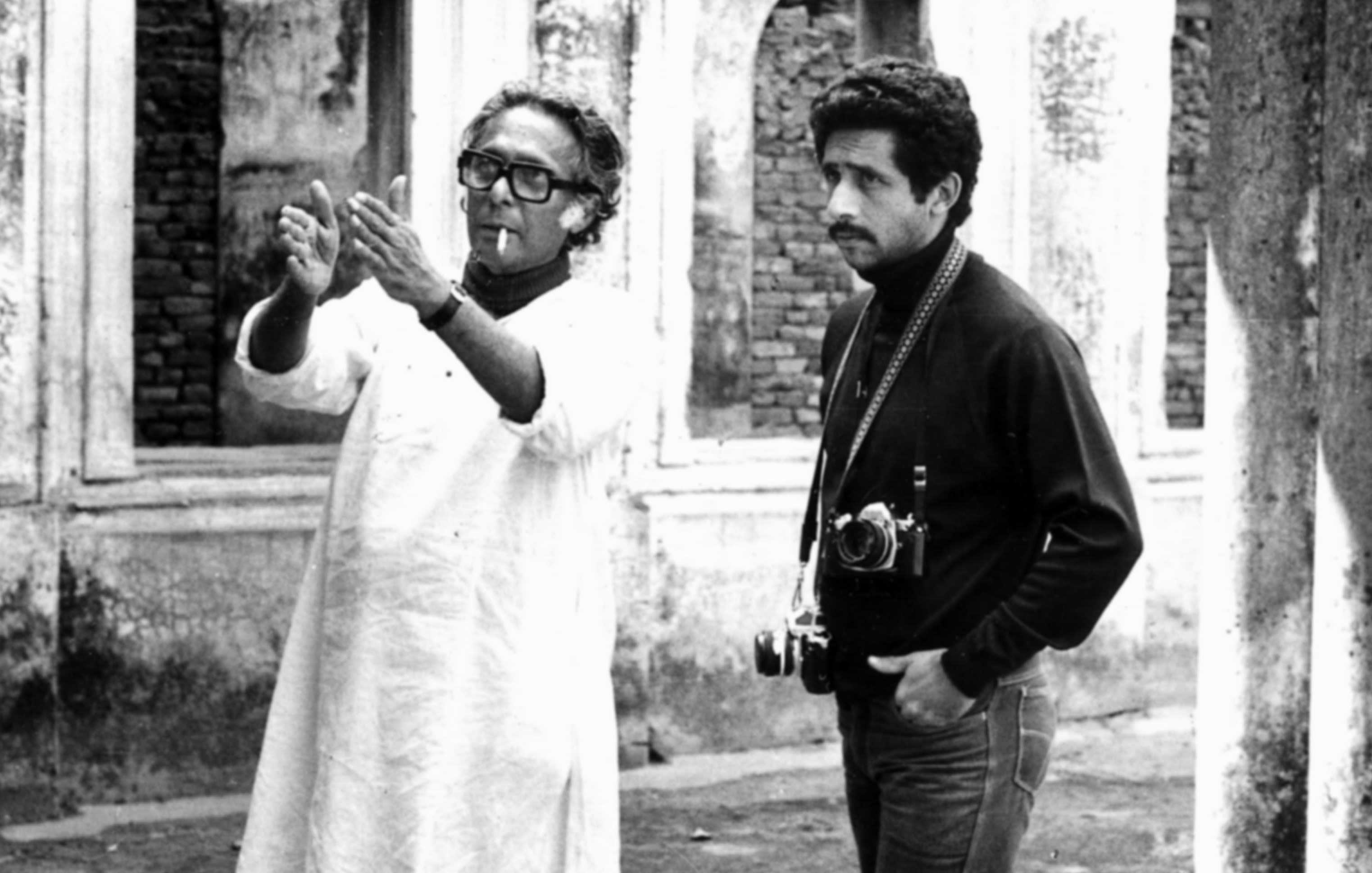

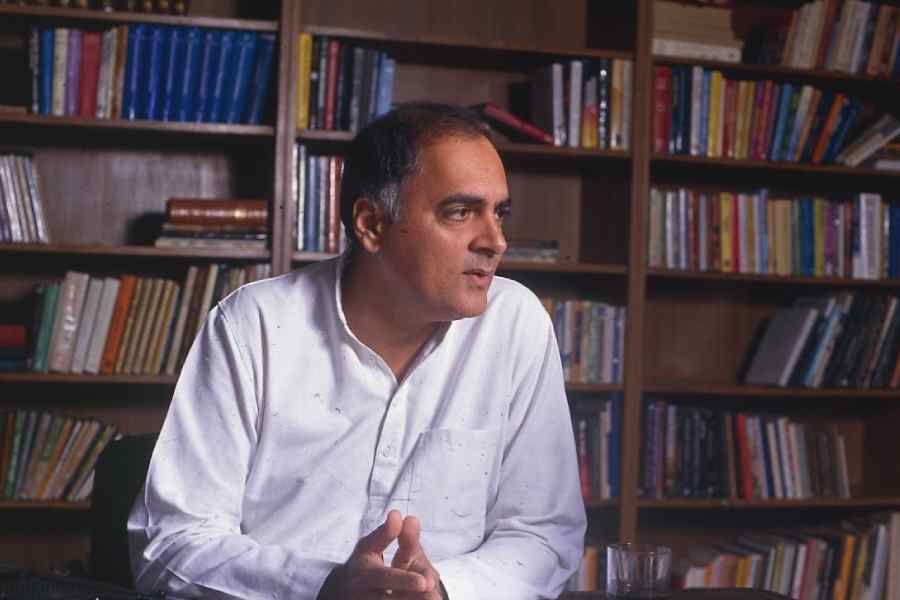

Has an age ended with Mrinal Sen’s passing? Dhritiman Chaterji in discussion with Raju Raman

Raju Raman: After Mrinal Sen’s passing, do you think this has been a kind of an end of an era as far as Bengali cinema, or even Indian cinema, is concerned, a marked era when a certain kind of films were being made?

Dhritiman Chaterji: Yes. Mrinalda had not been making films for a long time, but he belonged to a certain generation and a certain sensibility of film-making, which began with him, with Satyajit Ray, with Ritwik Ghatak, with some film-makers from Bombay and the south in the mid-1950s. Also one should mention names like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shyam Benegal. It is always difficult to label certain times as being absolutely distinctive. In cinema, as in all arts, one sort of sensibility, one way of doing things flows into another. There is a certain continuity. But yes, there are various signs, which are specific or unique to that generation of film-makers who began making films in the ‘neo-realist’ mode in the early mid-1950s. There were distinguishing features both in technique and, more important, in sensibility and aesthetics. Then cinema was informed by a distinct political consciousness, whether we speak of the cinema of Ray, Sen, Ghatak, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Benegal, they were distinguished by — call it political consciousness, call it social responsibility.

They were possibly triggered off by certain socio-political conditions existing in the country at that time...

Any art form is willy-nilly influenced by the context, by the sensibility of that time. The 1950s, post-Independence, the socialist kind of sensibility, Nehruvian dreams of nation-building, IPTA, people’s theatre movement, all of that inevitably had their influence. That was the only way to go. I mean, ideologically [laughs], being on the Left was the default position. I find it difficult to think of a prominent artist in any art form of that time who belonged to the Right.

Do you think that the global situation, the Vietnam War, the Students’ Movement of 1968 in France would have had any significant impact here because simultaneously we were having the Naxalite movement? Although they may not have had any direct connection one with the other. But would this kind of overall situation have prompted these Left-inclined creative people to project a certain kind of sensibility in their works?

As far as Mrinal Sen is concerned, let’s think of, say, Akash Kusum, 65-ish, I think... Now, just before that, through the film society movement in Calcutta and elsewhere, we were being exposed for the first time to the French package — Truffaut...

The French new wave...

I’m not talking about the politics here, but the techniques. The French new wave definitely had an influence on film-makers here at that time, who were part of what we now call parallel cinema. If we think of Akash Kusum, if we think of Pratidwandi, which is 1970. Because I never discussed this with Satyajit Ray, it would be presumptuous of me to say that there was a direct influence. But if we consider that Pratidwandi was in many ways a departure both stylistically and content-wise from the films he had been making earlier... One can’t help feeling that what was going on in the world, in Calcutta, and West Bengal, the ultra-Left movement — obviously, one of the characters belonged to that movement in the film — the sort of films Godard was making, the turmoil at the Sorbonne, all of that...

If one reflects on the film society movement, it really grew in the 1960s on films received from the East Bloc countries... Wonderful directors, Jirí Menzel and so on and so forth...

Yes. That is where we discovered Polanski, with Knife in the Water...

The exposure to film-makers from countries which were totally Left-inclined... that also could have had an impact on the sensibilities of film-makers here. Don’t you think so?

The short answer is yes, because the film-makers we are talking about were students of cinema in addition to being film-makers. So all of them kept up with what was going on in the world of cinema, whether in the Eastern Bloc or in Europe. Satyajit Ray was a great admirer of...

Hollywood films... And also Italian neo-realism. Bicycle Thieves...

Of course. De Sica. Pather Panchali. So it is very difficult to sequester one influence and say that this was the dominant one. If one compares Ray and Sen, all one can say is that Ray was more understated than Sen was, certainly during the Calcutta trilogy time, if you compare them to Ray’s Calcutta films — Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya — Sen is more explicit, more strident in expressing his politics. Ray more...

Restrained?

Restrained, sedate. But everybody coming from the same place. Everybody expressing their concern about contemporary society, contemporary reality, which is true a little later of Adoor, Shyam, of others.

Like even John Abraham.

Yes. There was... Aravindan.

Would you agree that in the films we are talking about, in that age, there was this streak of protest, an underlying thread in the films, anti-establishment, anti-societal norms...?

Yes, this has always been a matter of debate: how much can any creative artist, film-maker, writer, actually change what people do? I remember during the 1970s Shyam once saying that at most what we can do is bring about some kind of attitudinal change. I remember Mrinalda once having told me that he met Cesare Zavattini, one of the theorists of Neorealism, at a film festival. Zavattini said that [films] can’t change anything. Recently at a literary meet in Calcutta, Amitav Ghosh was talking about his latest book, and he said something I think is very interesting, that the most an artist can do is to tell people that I’m watching, I’m noticing, what is going on is not escaping my notice. Not only that, it is informing and shaping what I do. What effect it is going to have I do not know. But I am aware. This awareness of the artist. And expressing that awareness is the important thing.

What would you say about film-makers, like, say, Tapan Sinha.

Tapan Sinha, Asit Sen, Ajoy Kar, a number of them. When we were in school and college, films like Asit Sen’s Swaralipi, Saat Pake Bandha, Harano Sur, that whole genre, we used to absolutely love them... They were not political, not New Wave, not parallel cinema; they were solid middle-class cinema. But it was good cinema. They told stories, worthwhile stories, in what can only be called a cinematic kind of way. And the technicians, people like Ramananda Sengupta, whose disciples made the cinema of the triumvirate possible — I know ‘triumvirate’ sounds very lofty — I don’t think the triumvirate has at any time disavowed that debt... not to forget the fabulous work which was happening in Bombay and the south at that time technically... arrey, we just have to think of Guru Dutt. Technically solid work was happening elsewhere... It’s also been debated why Tapan Sinha did not get the same kind of artistic recognition as Ray, Sen, Ghatak did. The only reason I can think of is that he liked to be seen — and he was very good at it — primarily as a storyteller, not necessarily as a conveyor of ideas, if the ideas got through in his stories… As far as this business of political consciousness is concerned, Ray once told me two things: that ‘I always am conscious of the fact that I have a responsibility to the producer, I can’t be irresponsible with the producers’ money’. The other was that ‘my primary audience is the Bengali middle-class, simple as that...; I have to speak to them’... We were talking about the concept of rasika. Let us say classical music. Classical music is not for everybody, you need to be a rasika — aware of the grammar of music to really savour it. He said that applies to cinema too: ‘I have to keep in mind the general middle-class audience, for them I have to tell an engaging story; for the rasika, I provide ingredients, or clues, cues, to delve a little deeper into my narratives and to discover other things. I am intensely aware, conscious, I have to do both these things’. Can it be said that telling a story on the surface and doing other things below, at a subterranean level, are two devices... could you say that these two devices different film-makers used in different measures and in different ways? Ray used it in a certain way, Sen used it in a different way, Tapan Sinha in a third kind of way, I don’t know if that is one way to bring some clarity into this whole business of storytelling versus political consciousness.

The films of Ray or Sen, to a lesser extent, Ghatak, had a lot of exposure at the international level. Do you think that there are certain things at the subterranean level which may be culture-specific, and do you think an international audience would have seen these nuances in the same way as a local audience would have?

This may be a generalization, but I think this culture-specificity applies more to, say — let’s just take Ghatak — the trauma of Partition, that anguish which informs so much of his work. As a Bangali, or as an Indian, that resonates with you. Displacement as a concept resonates everywhere, but at an emotional level... does it resonate that much with a foreign audience? Or is it seen with a measure of detachment?