Ajinkya Rahane has become the first recipient of the Mullagh Medal. From 2020, every Player of the Match from a Boxing Day Test started receiving the Mullagh Medal, established in honour of Johnny Mullagh, a star from the 1868 Aboriginal tour of England. The Aboriginals of 1868 were Australia’s first sporting team to compete overseas. They have only recently been given their due in Australia’s cricketing consciousness.

India, however, is a very long way from celebrating its champions or paying formal tribute to their legacies.

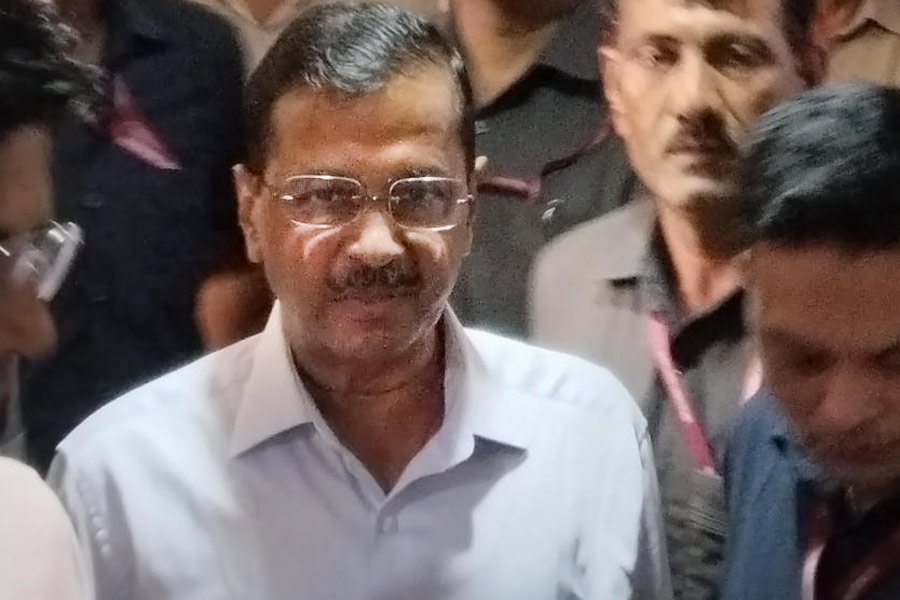

A day before Rahane received the Mullagh Medal, a statue of the late Arun Jaitley, the former finance minister and president of the Delhi & District Cricket Association, was unveiled at the Feroz Shah Kotla. The former India cricketer, Bishan Singh Bedi, had protested vehemently, saying Jaitley could be remembered in Parliament as a politician but “not [in] a cricket stadium”. Bedi had many run-ins with Jaitley’s presidency, terming it a “corrupt durbar of sycophants”, and wanted his name to be taken down from a Kotla stand. Bedi also surrendered his DDCA membership. The Kotla has already formally been named the Arun Jaitley Stadium but there appears to be no limit to servility, particularly now that Jaitley Jr, Rohan, has been elected the new DDCA president.

Public objection to the Jaitley statue was interpreted as a challenge to the ruling dispensation’s higher standards of stadium nomenclature. In defence of Jaitley’s statue in the stadium, whataboutery101 cited the obscene number of sports arenas — 28 — named after the Nehru-Gandhi clan. Sixteen for Jawaharlal Nehru, seven for Indira Gandhi, and five for Rajiv. Since most Indian stadia are government-owned, their political scorecard is long and distinguished: Rajendra Prasad (three), Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy (two). A rough count of other single-stadium politicians crosses 10.

Of the handful of grounds named after athletes, hockey used to be proactive: Dhyan Chand, K.D. Singh Babu and Roop Singh (Gwalior’s cricket stadium). There’s a Bhaichung stadium in Namchi, Sikkim, and Coimbatore’s Kari Motorway Speedway honours the motorsport pioneer, S. Karivardhan. The figure for cricket is zero because the more self-aggrandizing cricket administrators also chose to name grounds after themselves — M.A. Chidambaram, M. Chinnaswamy, S. Wankhede who, in turn, inspired tennis’s R.K. Khanna. Mohali’s PCA-I.S. Bindra stadium was anointed a year after Bindra retired from cricket administration, only to be elected chairman in 2015, which appears to be a ceremonial post.

How many statues does India have of its finest athletes? Not Madame Tussauds social media wax works but real ones. Some of the names that come to mind the quickest are those of Dhyan Chand, C.K. Nayudu, D.B. Deodhar and the footballing hero, Gostha Pal, opposite the Eden Gardens. Calcutta also acknowledges Leslie Claudius and Shute Banerjee. Plus there’s Vinoo Mankad in Jamnagar, Gujarat, Sachin Tendulkar in Atarwalia, Bihar, Yuvraj Singh in Ferozepur, Punjab, and Sourav Ganguly in Balurghat, Bengal. That’s only 10 in all and there are no women among them.

It is patently clear that our sport is not an engine of or for athletic excellence. In India, sport is a centrifugal force-generator for political power and its allied sycophancy industry. So here’s a thought. Let’s treat the stadia like the politicians treat sport — by cutting across party lines to exercise our love for sport in the most fitting manner.

Since renaming, demolishing and appropriation — cities, institutions, programmes — are the policy du jour, what stops the ruling dispensation and their cheerleaders from passing a bill in Parliament to rename every single politico-inspired ground after India’s greatest athletes? One nation, one sports policy: no politics in sport. It will free our sporting venues from their political names and rid us of a 70-year-old habit.

In an atmosphere of political disinvestment from sport, the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna also requires a sport-centric title. And while we’re at it, surely the most inappropriately-titled Indian sports award — the Dronacharya — must be renamed. How can an award for coaching be named after a coach who cut off the thumb of a student who secretly studied archery after he was first shooed away by the coach? What kind of coaches are we recognizing? Let’s name the award after a real Indian coaching legend — football’s Syed Abdul Rahim who took India to the 1956 Olympic semi-final and the 1962 Asian Games gold medal. No patriotic Indian sports fan should have any objections.