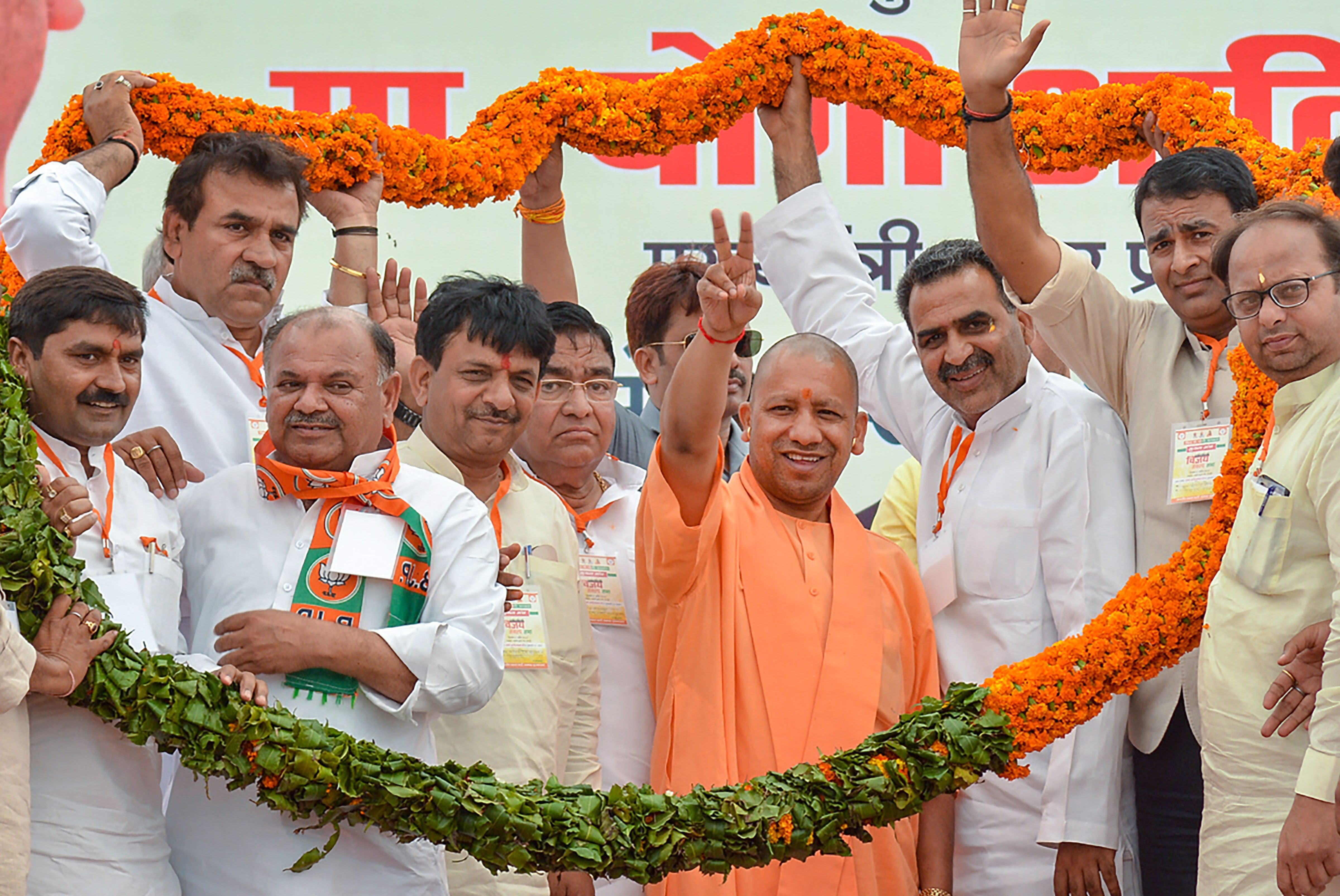

The Indian political arena in 2019 is hardly the space for a league of gentlemen. Yet it must have been some vague image of fair play that underlay the conception of the Election Commission’s model code of conduct. For although the EC has full powers to conduct the elections, it cannot penalize political leaders who violate the MCC beyond asking them to explain and then censuring them, sending letters of complaint to the president, or, at most, lodging a first information report in case a law, such as that against incitement of hatred, has been violated. Presented with a set of leaders who cannot care less about institutional propriety — rather, they revel in turning rules inside out with cunningly applied technicalities — the EC appears to have lost its bearings. It forbade the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh to use the army for the purpose of winning votes after he called it “Modiji ki sena”; Yogi Adityanath has now said that voting for the Telangana Rashtra Samithi is encouraging Nizam Shahi rule, since its ally is an ‘anti-national’ party, the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, and, again, as in the “Modiji ki sena” speech, that the Congress feeds terrorists biryani. The Indian Union Muslim League has sought to file an FIR against Mr Adityanath for telling voters, mistakenly or deliberately, that the IUML was responsible for Partition. The EC complained to the president against the partisan remarks of Kalyan Singh, who, as governor of Rajasthan, should not have been campaigning for Narendra Modi: the president has sent the letter to the home ministry as is routine.

The EC obviously cannot penalize MCC violators in a way that they would be disadvantaged in the elections. But is that really the end of the story? The perception of a relentlessly vigilant and strong EC could be expected to have an effect on campaigners’ behaviour. Even public and repeated censure and instant responses would have had an effect, if just on the voters. Instead, the EC’s delays and ditherings suggest a willingness to let strong, coercive forces have their way; the EC’s decisions, such as that regarding Mr Modi’s Mission Shakti speech, are clouded by convoluted reasoning, its double-takes regarding the Modi biopic embarrassing, and its indecisive response, so far, to Namo TV suggests that the MCC is unnecessary for the ruling dispensation. Limited powers may be a problem, but the disappearance of a spine is a different issue altogether.