With the publication of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific last month the elucidations of the concept have expanded. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations statement follows that of Australia, the United States of America, Japan, France and Indonesia. For each, the conceptual rebalancing the term implies is directly related to the new factor in this region — Chinese maritime assertion. India’s position, too, on the Indo-Pacific is related to this new factor in its geopolitical environment but it has also older antecedents that are equally significant.

There was more than the usual interest when the prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, rose to address a joint sitting of the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha in August 2007. He had then been in office for less than a year but came from a well-known political family. His grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, was the first Japanese prime minister to have visited India when he did so half a century earlier. Abe in his speech invoked the Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh, and, in particular, the title of a Sufi text he authored in 1655, Majma-ul-Bahrain. This translates as ‘Mingling of the Two Oceans’. Dara Shikoh’s purpose was finding common ground between the two universes of Islam and Hinduism. For Abe, Dara Shikoh’s title was, however, the perfect metaphor for a “broader Asia”, one in which the “Pacific and the Indian Oceans are now bringing about a dynamic coupling as seas of... prosperity”. India and Japan, Abe’s point was, had the ability and the responsibility to broaden Asia even further and “to nurture and enrich these seas to become seas of clearest transparence”.

This statement, in sketching out a new geopolitical category comprising the Indian and Pacific Oceans, did not use the term “Indo-Pacific” itself but certainly anticipated it. The concept gained traction slowly. To a great extent, the ongoing global war on terror and the global financial crisis acted as dampeners. In any event, its time would come in the next decade as growing Chinese maritime assertion focused minds on this common space. The ‘Indo-Pacific’ has since firmly entered the political and diplomatic lexicon.

In spite of the borrowed metaphor from Dara Shikoh, Abe’s idea was primarily a geopolitical construct. He spoke of India and Japan as Asian democracies, of the strategic global partnership that bound the two governments and how this was going to be a pivot for the “outer rim of the Eurasian continent”.

Perhaps Abe’s reflections that day struck a chord in India for other reasons apart from the compelling geopolitical logic that faces India as its foreign trade expands and this rapidly increases its dependency on the maritime domain. These reasons derive from other constructs of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ which past scholars, activists and intellectuals in India had attempted to formulate as equally important to India’s lived experience and memories of its history.

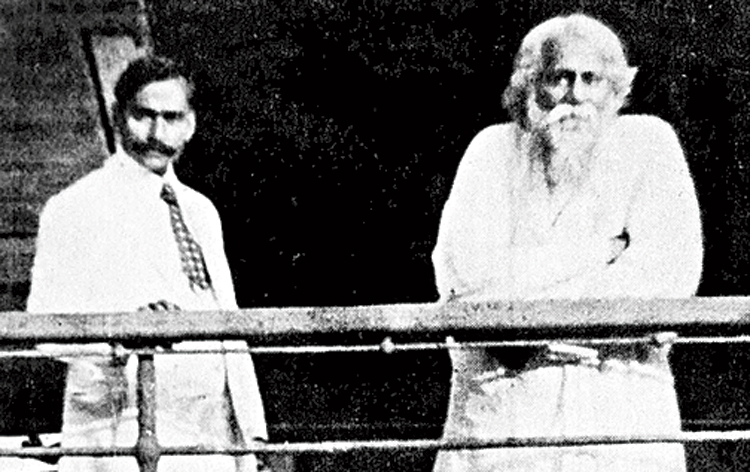

In modern India, perhaps the first conscious use of the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ was by the noted scholar, Kalidas Nag, and it is found in his 1941 book, India and the Pacific World. For him the term referred to largely a cultural and civilizational entity. The impulse to trace India’s links with this maritime universe had much to do with his association with Rabindranath Tagore. Kalidas Nag wrote, “Sailing in 1924 with Dr. Rabindranath Tagore into the Western Pacific, I was blessed by the Master Poet in my endeavour to trace the cultural and artistic relations of India with the nations of the Far East: China and Japan, Java and Bali, Champa and Cambodge, Malaya and Burma”. Kalidas Nag thereafter sought to give an institutional form to these “thousand points of historical contact and cultural relations” and this took the form of the establishment of the “The Greater India Society” in 1926 and its journal, The Journal of the Greater India Society, which appeared from 1934 to 1959. Scattered through its issues are the efforts of historians, linguists, anthropologists and other scholars exploring the points of contact between India and its vast maritime neighbourhood through history. Works such as K.N. Nilakanta Sastri’s South Indian Influences in the Far East (1949) or R.C. Majumdar’s Hindu Colonies in the Far East (1944) and earlier similar works were part of this scholarly tradition.

If Rabindranath Tagore has been the impetus for this largely scholarly endeavour, Mahatma Gandhi was responsible for another dimension of India’s Indo-Pacific perspectives — diasporic relations. Charles Freer Andrews thus wrote a book titled India and the Pacific (1937) that detailed his experience of working with Indian workers in faraway places beginning with his visits to Fiji in 1915. The emigration of Indian labour showed to Andrews an even broader canvas than the Pacific. He noted there had been “strangely little realization as yet, even in India itself, how far the emigration of Indian indentured labour had spread”. Thus, apart from Fiji and the Caribbean, there was Mauritius and, as Andrews noted, “Natal owes most of its development as the ‘Garden of South Africa’ to Indian labour”.

It has been estimated that in the century from the 1830s some 30 million Indians travelled overseas from India. Along with this vast movement of labour were entrepreneurs in capital. In the early 1870s, Bartle Frere, a former governor of the Bombay Presidency touring in the East African coast had noted that “all trade passes through Indian hands... and without the intervention of an Indian either as capitalist or as petty trader, very little business is done”. This presence extended beyond East Africa and Frere had also noted, “Along nearly 6000 miles of sea coast, in Africa and its islands, and nearly the same extent in Asia, the Indian trader is, if not the monopolist, the most influential, permanent, and all-pervading element of the commercial community.”

This pervasive spread of Indian labour and capital owed much to the phase of globalization under the aegis of the British empire and the fact that the vast space of the Indian Ocean was a “British Lake”. This imperial system had as its base Indian labour, Indian business and, not to forget, the Indian policeman and the Indian army. All this was dramatically illustrated by the building of the Ugandan railway at the end of the 19th century, described then as the “driving of a wedge of India... across East Africa”. This Indian expansion under the imperial aegis is as much an antecedent of the Indo-Pacific as any other.

From an Indian perspective, then, the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ can be seen as the convergence of a number of constructs — the geopolitical and the strategic is only the most recent. None of these constructs is or should, however, be seen as static.

The Greater India Society approach had evident limitations. The Indian imprint in Southeast Asia was not a direct transference of influence but it was rather a fusion of ideas and cultures. The indigenous societies of Southeast Asia retained far greater agency over the ideas they imported than happens in colonial conditions — a point R.C. Majumdar and other historians may not have conceded in the 1930s and 1940s. Indian labour and capital expanding all across the Indian Ocean littoral was deeply resented by many as part of an exploitative colonial intrusion and the pushback against this in the 1950s and 1960s was inevitable. In spite of this the Indian connection had durability and has endured.

The current interest in the concept obviously is political and directly linked to the expansion of Chinese influence and presence across the littorals of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Notions of the Indo-Pacific may thus further evolve depending on the quality of China’s future interface with others.