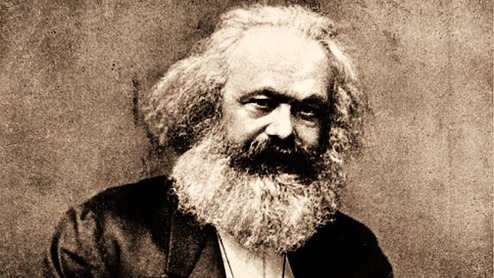

Karl Marx continues to be debated for his critique of capitalism. One of his important critiques, alongside that of growing inequalities under capitalism, was of the growing sense of alienation. His early writings referred to alienation of a spiritual kind where the “species-being” that had inner morality and compassion remains disengaged and suppressed under capitalism. However, the ‘later Marx’ began to emphasize a more structural and technical aspect of alienation, wherein the workers are divested of the process as well as a sense of satisfaction, pride and identification with their product; instead, the division of labour pushes them into mechanical and repetitive work in order to improve efficiency at the cost of human sensibilities and the urge for recognition.

The anthropologist, David Graeber, pointed to the phenomenon of what he termed as “Bullshit Jobs” under capitalism. ‘Bullshit Jobs’, he argues, are “a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.” Such jobs do not add to the self-worth of the employee and are, on the contrary, meaningless. They are more about the perceived need to manage the workforce. But one could extend this to argue that this malaise of meaninglessness and worthlessness has become all-pervasive, and that it is only set to grow further with the rise of automated work and the introduction of Artificial Intelligence in the years to come.

The sense of satisfaction in what we do is depleted because we become a tiny, unremarkable part of the process, often referred to as the ‘cog-in-the-wheel’, where the work is repetitive, boring, and does not generate curiosity and creativity. The sense of something being spontaneous is being replaced by algorithmic, arithmetic and financial considerations. The historian, Yuval Noah Harari, says that ‘algorithm’ is the single- most important word of the 21st century. This is further compounded by what the development economist, Guy Standing, refers to as the new precariat working conditions of being on time-bound contracts with the declining number of permanent jobs that offer such benefits as pension and medical care. Work, thus, becomes a source of both insecurity and meaninglessness.

Many scholars, including Standing and Graeber, have identified universal basic income as one possible alternative to the phenomena of ‘Bullshit Jobs’ and precarious working conditions. However, as Amartya Sen has argued, employment is not merely about income; it is also about self-fulfillment and satisfaction. Under modern capitalist conditions, the sense of self and recognition are being replaced with or compensated by what the Marxist geographer, David Harvey, refers to as “compensatory consumerism” wherein the market is flooded with products that give us temporary, but instantaneous, gratification. Consumption has become the new leitmotif of life, and it continues to drive our instincts and appeals to our sensory and visceral needs. The question of satisfaction and meaning keep getting back at us, while we tend to ward them off through newer gadgets, technological innovations, and modes of communication. Spiritual questions are being displaced rather than being answered. Newer modes of consumption — Harvey refers to these as non-exclusionary modes and cites the example of Netflix — have emerged where the product can be consumed simultaneously by many and also instantaneously. New kinds of shopping experiences in malls create newer spatial experiences — Frederik Jameson refers to these as being neither public nor private — that leave behind a sense of depravity, transforming consumption into a repetitive, boring, banal act.

Marx had predicted this loss of control over sense and sensibility, a time when we will come to see, mediate and replace human relations with commodities. It is a condition where exchange-value dictates the use-value of goods: he referred to it as ‘commodity fetishism’, which, in turn, adds to the sense of alienation propelled by the working conditions and the nature of the jobs.

The modern condition of alienation, however, is not limited to market, jobs and consumption. It extends to social, personal and political life as well. The State and its notions of sovereignty and territoriality are markers of their own versions of alienation on the populations they govern. Contemporary democratic means of representation have pushed forth centralization of power, exceptionalism and exclusion. Representation has become more a condition of alienating the collective rather than of mediating collective interests. Recent global protests, from ‘Arab Spring’ to ‘Occupy Wall Street’, are reminders of alienated collectives struggling to identify with the political life of the nation. This has led to varying demands — from electoral reforms to direct democracy to blatant forms of authoritarianism. The underlying sense of alienation from the collective is, today, articulated as the ‘crisis of representation’ and anger against corruption.

There is a need to explore the relationship between ‘compensatory consumption’ and the ‘politics of presence’ characterized by sectarian identity politics. The underlying condition for both seems to be a lasting and gnawing sense of alienation from self and collective. The new modes of imagining durable solidarity that is secure and meaningful has become a pressing need to fight capitalism and preserve democracy.