Tomorrow, India will celebrate its 76th Independence Day. India is also leaping forward as a fast-growing economy. This is not a small achievement. While celebrating these achievements and looking towards the future, it may not be out of place to turn to the immediate past and revisit the complexity embedded in the early stages of India’s struggle for independence.

The British colonisers brought modernity to India and, along with it, a dilemma. Accepting modernity would be tantamount to accepting colonialism for Indians. At the same time, rejecting modernity would leave India premodern, both economically and politically. This galvanised the Indian thinkers into exploring alternatives and creating radical solutions to make a case for independence.

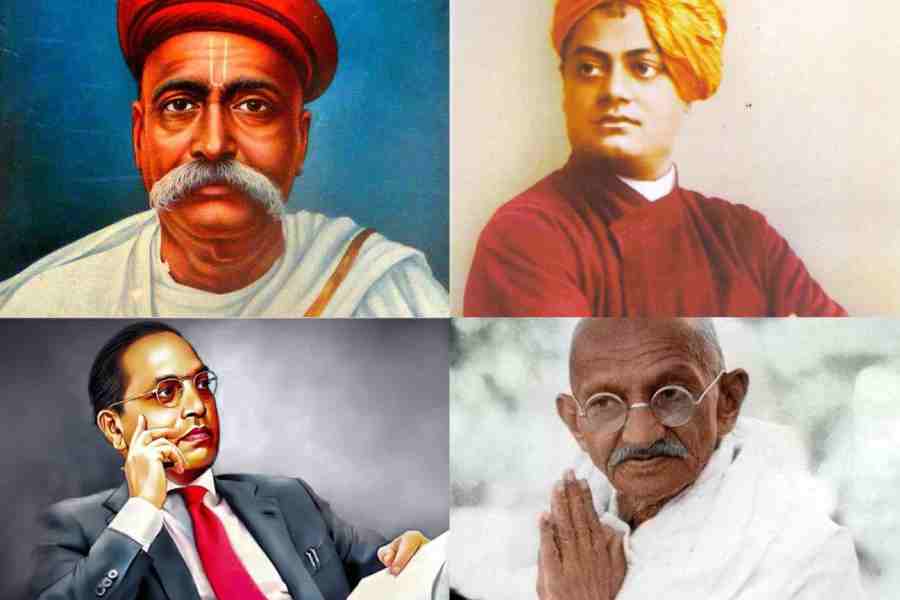

They decided to delve into the past for insight and inspiration. This was, of course, prompted by necessity rather than choice. But while the Indian leaders followed a similar path of revisiting the past, their varied viewpoints and innovative approaches kept them from becoming orthodox and stagnant. Reviewing Sankhya, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay concluded that the impact of this school of philosophy on “Indian civilization as a whole is unparalleled.” On the other hand, Bal Gangadhar Tilak turned towards the Bhagavad Gita and wrote Gita Rahasya, perhaps the first systematic modern work on the Gita. Swami Vivekananda claimed that Advaita can “stand the test of modern reasoning” similar to that of modern physical research. Sri Aurobindo followed the Upanisads and Advaita, while Mahatma Gandhi praised the Gita and Jainism for advocating ahimsa. B.R. Ambedkar admired Buddhism and felt that “Buddhist Bhikshu Sanghas disclose[d] that not only there were Parliaments [in India] — for the Sanghas were nothing but Parliaments — but the Sanghas knew and observed all the rules of Parliamentary Procedure known to modern times.”

So while there was convergence amongst the modern Indian thinkers on how they chose to revisit the past, there was also enough plurality and diversity in their approaches and conclusions to avoid complacency. For instance, a “spirit of renunciation or detachment [bairagya],” a predominant aspect in Sankhya responsible for the “lack of an activist spirit, so commonly identified with the Indian character …,” led Chattopadhyay to conclude that Sankhya’s theory of renunciation and the associated ‘fatalism’ are responsible for Hindus losing freedom. It is another matter that Chattopadhyay treats the period preceding it as positive while rejecting the immediate past following Sankhya. Therefore, he revisits Sankhya not to endorse it but to denounce detachment and renunciation.

Tilak, on the other hand, held the Gita in high esteem but rejected the long legacy of the interpretation of the Gita — the bhasyas of all acharyas, including Shankaracharya, Ramanujacharya, Madhavacharya, Vallabhacharya and others. He wanted to save the Gita from “the clutches of the commentators” and alleged that these bhasyas, using Mimamsa, are Gunanuvadas. Bhakti was overemphasised at the cost of karma, which, he claims, is contrary to the original message of the Gita, which is “Energism (Karma Yoga).” For Tilak, the “original Gita did not preach the Philosophy of Renunciation (nivrtti).” He alleged that the undermining of karma in bhasyas was responsible for Indians neglecting the material world, culminating in India losing her freedom.

Other modern Indian thinkers followed the formula of recalling aspects from the past, accepting the ones that could be beneficial and rejecting the parts that would not be helpful. Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo rejected classical philosophy’s neglect of the material world. They rejected hierarchy, inactivity, and superstitions in Indian society and stressed the urgent need to remove poverty. On the other hand, Gandhi accepted the Gita and other texts from the past but denounced the evil practice of untouchability. He rejected the story of a shudra being punished by Ramachandra for daring to learn the Vedas as an interpolation. He disagreed with interpreting the Gita as a text promoting war and violence. Ambedkar denounced Hinduism for promoting caste and the practice of untouchability. In his essay, “Annihilation of Caste”, he maintains the removal of Hinduism as the precondition for the removal of untouchability.

While there is convergence among the nationalist leaders in choosing to remember the past, their differing, dynamic approaches keep them from being bogged down in history. They rejected aspects of the past that they felt were responsible for the colonisation of India. It is this very complexity that highlights the uniqueness and the vulnerabilities in modern India. The underlying critical thinking and the plurality of recalling formed the foundation of an independent nation. It is imperative to both recognise this foundation and inculcate this enduring value.

On closer scrutiny, we can see a formula in the writings of modern Indian thinkers: their understanding of complex and critical problems created by the British to rule India, namely, their use of modernity to justify their rule of India; their perseverance in pursuing solutions by exploring alternatives, such as remembering the past, to make a case for India’s independence; their diligence in rejecting what is not good from the past and accepting what is useful.

Reflecting on our immediate past can better illuminate our understanding of the nature of India’s independence. An independent India can consider this underlying formula to think about 76 years of Independence and assess both the good and the bad. This revisiting can throw better light on setting the agenda for the coming 25 years when India completes 100 years of Independence. This can also save India from becoming obsessed with unreflected unity.

A. Raghuramaraju teaches Philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology, Tirupati