Like alchemy, which was an obsessive concern for the medieval world, modern democracies are forever preoccupied with unearthing the secrets of winning elections. In the not-so-distant past, striking the right note with the electorate was left to the political instincts of leaders. With the gradual transformation of politics into a ‘science’— an invention of American universities seeking to harmonize different experiences — there is a growing temptation to outsource the election business to professional strategists. Whereas political parties earlier sought professional help from pollsters — to track shifting moods — and advertising agencies — to effectively communicate messages and build a public profile — there is an emerging tendency to outsource the entire campaign to political consultants whose levels of competence and understanding are uneven at best.

The debate over the right strategy to win elections is both unending and inconclusive. Burrowing into multiple studies by journalists, academics, and participants of an election — the Nuffield College studies on every British general election since 1945 is an example — is always rewarding. However, at the end of the day, it is generally recognized that no two elections are alike and that a successful past strategy is no guarantee of future success. There is a large measure of uniqueness to every election, and, in India, matters are further complicated by the sheer diversity of the states and the different political traditions at play. Often, things move beyond the anticipated variables. The victory of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016 was one of the most spectacular electoral upsets in recent times. The dramatic outcome, however, can barely be explained by merely extrapolating past trends. A critical difference was made by white Americans in the lower end of the economic ladder who had not bothered to either register or vote in earlier elections.

Nearer home, the rich history of Lok Sabha and state assembly elections — particularly after they ceased to be simultaneous after 1969 — has established a rich fund of data on electoral behaviour. Based on these, some broad conclusions are in order.

First, there is an increasing mismatch between how people vote in the Lok Sabha elections and who they prefer for the Vidhan Sabha. National parties tend to add to their votes in Lok Sabha polls. This was most apparent in Odisha in 2019 where, on the same day, the Bharatiya Janata Party registered a spike in its parliamentary vote compared to its Vidhan Sabha vote. This was also apparent when the BJP failed to equal its 2019 general election vote in Bengal’s assembly election of 2021.

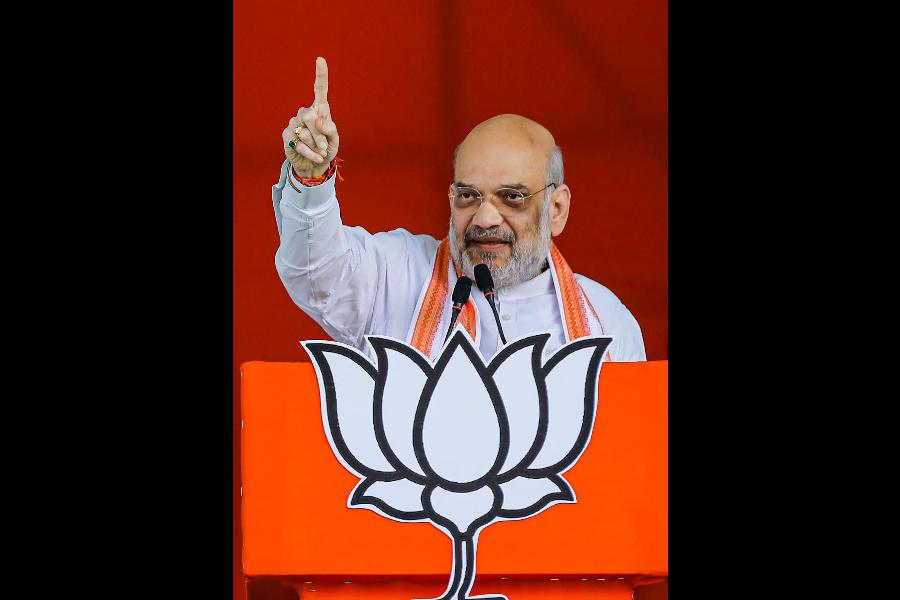

Secondly, Lok Sabha elections from 1952 to 1984 were in many ways votes of confidence or no-confidence in one towering leader. This pattern was broken from 1989 to 2009 when parliamentary elections increasingly became a series of regional elections, resulting in nearly 25 years of (sometimes unstable) coalition governments. Even otherwise tall leaders, such as Vishwanath Pratap Singh and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, weren’t entirely successful in transforming Lok Sabha polls into presidential elections. It was Narendra Modi in 2014 who resumed the pattern established by Jawaharlal Nehru and, more so, Indira Gandhi — even the 1984 election that was nominally dominated by Rajiv Gandhi was centred on her martyrdom. Despite the scepticism of the punditry that believed there were natural limitations on the growth of the BJP, particularly in the non-Hindi belt, Modi has led the BJP to an absolute majority in two successive elections. In the process, he has also made politics more presidential at the national and the state levels. The regional parties were the unintended beneficiaries of this process at the state level since their existence is based on a single leader or one family. Even otherwise institutionalized parties, such as the Shiromani Akali Dal and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, have succumbed to the lure of dynastic control. Mamata Banerjee, too, has injected the dynastic principle in a state where the pretence of democratic enlightenment runs strong.

Finally, while the presence of a strong leader is undeniably appealing to Indian voters, it is a necessary but not sufficient precondition of success. Firm, no-nonsense leadership must be backed up by a clever cocktail of State-sponsored welfarism and identity politics. In the pre-liberalization era, welfare schemes that benefited the poor directly were a rarity. Governments lacked both the means and the mechanism to put money in individual pockets. Consequently, the thrust was on development works, the expansion of government jobs, establishment of public sector units, and a culture of cronyism based on the belief that some of the benefits would invariably trickle down. Following the post-1992 swelling of State revenues — the goods and services tax has speeded up the process — and the introduction of Aadhaar, targeted distribution of sops has become feasible. From the Delhi government’s subsidy of water and electricity, Odisha’s subsidized rice scheme to Mamata Banerjee’s Lakshmir Bhandar, state governments are competing with targeted schemes, such as the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana and the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi, of the Modi government.

However, this isn’t enough. Motivating voters also necessitates an emotional appeal, often based on identity — be it language, community, or faith. It was N.T. Rama Rao who set the ball rolling by invoking Telugu pride against a supine Congress that allowed itself to be kicked around by Delhi. On his part, Lalu Prasad used subaltern assertiveness to offset legitimate charges of whimsical governance. In West Bengal, where there is an overlayer of ‘progressive’ thought, the Left Front coupled its cultivation of angst and anger with a subtle Bengali sub-nationalism. The latter was successfully picked up and utilized by the Trinamul Congress in 2021 to paint the BJP’s Hindu nationalism as culturally alien to Bengali society. In Gujarat, Modi used Gujarati pride with devastating effect in his management of the post-Godhra riots fallout. These examples certainly indicate the importance of identity politics, but they also suggest that it works on a sustained basis when complemented by wholesome governance.

The logic of the past isn’t always a guide to the future. But in view of the forthcoming assembly election in Uttar Pradesh, it may indicate why Yogi Adityanath starts as the favourite.