“Tere maathey ka ye aa’nchal bahut hi khoob hai lekin/ Tuu is aa’nchal se ek parcham bana leti to achcha tha (This veil of your forehead is very good but/ If you would have made a flag from this veil, it would be better).”

This couplet was written by Majaz Lakhnawi (1911-1955), who was very much active when India became independent following Partition on religious grounds. These lines were from his poem, “Naujawan Khatoon se Khitaab (Address to a Young Lady)”, which was composed in pre-divided India to instil the nationalistic spirit and fearlessness in women against a British rule that was increasingly becoming tyrannical. Majaz found in women a great potential of fighting spirit and fearlessness, which were necessary to deepen the impact of the freedom struggle.

As a poet of the Progressive Writers’ movement, he had a firm belief in the secular foundations of India that were laid down by the Constitution. He, like other poets figured in this article, rejected the idea of a new Muslim country and continued to instil in people love and faith for India through poetry.

These lines by Majaz seem to be coming alive 72 years after Independence as young women filled with love for India rise in protest, breaking the sartorial and behavioural stereotypes attached with their feminine and religious self.

Students of Jamia Millia Islamia defend a male student who was being beaten up by Delhi Police (Twitter)

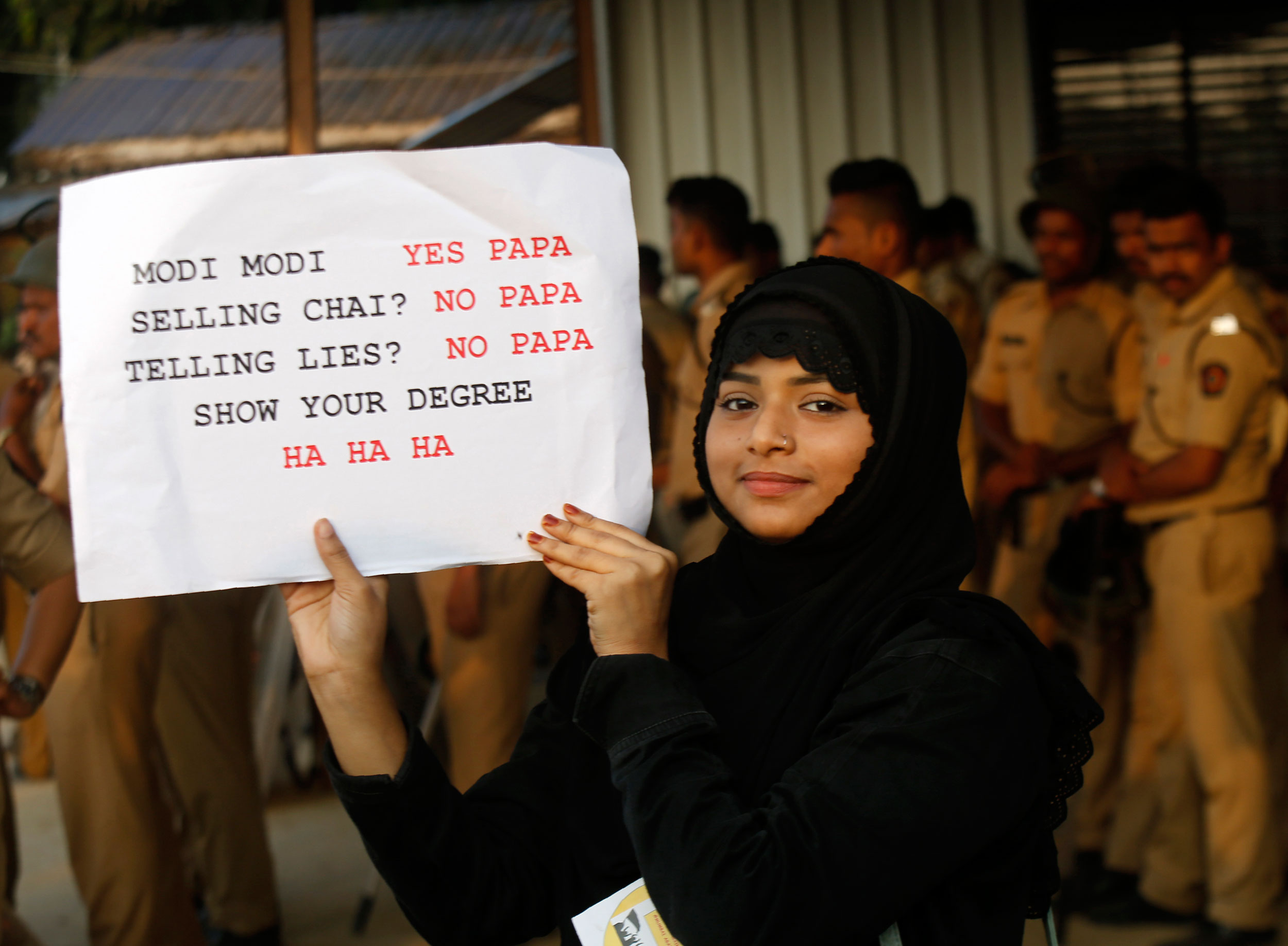

Images of female students — mostly hijab-clad — that emerged from Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, standing at the forefront of the protests and shouting slogans fearlessly against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the National Register of Citizens caught the attention of the media.

However, what shook the conscience of the people were the images of female students during the brutal attack by an armed police in Jamia on December 15, 2019. These photographs showed them facing police brutality fearlessly and rescuing their male friends from the lathis of the police.

The sight of hijab-clad students — they are usually misunderstood and their political consciousness underestimated — captured the popular imagination and spurred many in the student community to rise in protest against the present regime. Their struggle is to safeguard the secular character of the Constitution during a time when right-wing fundamentalism has been strategically transformed into various forms of populism that appeal more swiftly to the psyche of the common man.

Is this feminine outburst spontaneous or transient? It is a result of built-up dismay over the exclusionist and incongruent policies of the present regime. Though they bore other forms of social and political persecutions over this period of time, silently enduring the CAA and the NRC went beyond their cognitive capacities.

The resistance also comes from their sensibilities of the natural rights of a citizen of India that are being challenged. Their protests on the streets in biting cold are also their assertion that no regime should question their status as natural citizens of India.

It is an attempt to reclaim their space in the political and educational realms in India, which they thought belonged to them. Their anxieties also emerge from the experience of the psychological persecution of their community, with its loyalty towards India being questioned time and again.

In the past four to five decades, Muslim women in India have struggled to create a space for themselves in the public sphere by striving against the patriarchal normative of their own community. Their internal struggle proved to be impactful as they felt protected by the Constitution, which instilled in them fearlessness to fight against domestic oppression. Moreover, their mobility from smaller towns to cosmopolitan cities for education exposed them to a world of opportunities and possibilities to express their talent and skills. Over a period of time, they have also built intimate networks based on friendship, love and, above all, humanity — universal emotions defying the perimeters of religion, region and caste. The sight of their new world crumbling before the communalized agenda of Hindutva shook them and brought them out on to the streets.

Their anger is visible on the streets because the constitutional security that worked as a shield for them in their internal struggle for liberty is being snatched away through the CAA and the NRC. The very fact that they are on the streets does not show them to be ‘unpatriotic’. On the contrary, it testifies to the fact that they still feel protected by the Constitution that gives them the right to protest.

Apart from university students, women were seen in large numbers registering their resistance against the legislation in many parts of the country. In Aligarh itself, more than 1,000 women sat on the road on December 16 to pressurize the police to release detained students.

The change in the perception of men towards women is also visible throughout the movement. For them, women are no longer docile entities but active political actors to be kept at the forefront of the protests.

A similar need to include women in the political struggle was felt during the freedom movement when nationalist leaders and poets alike appealed to women to come out on to the streets against British imperialism.

While Gandhiji sought the active participation of women in the freedom struggle, poets of his time encouraged them to be significant actors in national politics.

The lines from Salam Machhli Shahri’s poem, “Dulhan (The Bride)”, tell us about the expectations of men from their prospective brides during politically turbulent times. They appeal to women to break the shackles of modesty associated with their existence and become active participants in the rebellion against the tyrant rulers: “Mujhe to hamdam o hamraz chahiye aisi/ Jo dast e naaz mein khanjar bhi ho chupaaye huye/ Nikal parey sar e maidaan udaa ke aanchal ko/ Baghaawaton ka muqaddas nishaan banaye huye/ Utha ke haath kahe inquilaab zindabaad! (I need a partner and a confidante/ Who does hide a dagger in her delicate hands,/ And goes out at the frontier, shedding her veil/ Leaving a sign of devout rebellion,/ She raises her hands and hails for revolution!)”

A Muslim woman participates in a rally against the Citizenship Amendment Act in Mumbai on Friday. (AP)

Although written in a different temporal and political context, these lines still hold significance and show that the role of Muslim women in shaping the political consciousness should not be underestimated.

University students pose a graver challenge as they are intellectually equipped to understand the political strategy of the right-wing ideologues where basket categories such as ‘nationalism’ and ‘mythical history’ are used to create national ‘heroes’ by invoking a glorious past wherein only Hindus were the legitimate citizens of India.

These heroes also require villains to be counterpoised against them so that they could garner some chivalrous validity. The most convenient thing in this already vulnerable situation is to pick villains from the ‘Other’ communities and present them as illegal immigrants and foreigners in order to further their politics of structural exclusion.

The trajectory of their actions and armed attacks on students highlight an organized effort to silence any form of dissenting voices that can be a threat to them.

AMU and Jamia were pointed targets for them as they could also garner communal mileage by presenting the students as betrayers of the nation and, ultimately, betrayers of the majority population, which, according to Hindutva, can only have a primordial connection with the ‘nation’.

Their obscurantist methods, however, did not appeal to a large mass of rational minds that universities produce. The youths of the country — not governed by the normative of religious divisions — stood up in solidarity, not merely to reclaim their constitutional rights but also to reclaim India where they can co-exist fearlessly.

Ali Sardar Jafri’s poem, “Jawaani”, echoes the spirit of the youth that surrounds us today: “Haqiqat se meri kyuu’n bekhabar duniya e faani hai/ Baghawat mera maslak, mera mazhab naujawaani hai (Why is this transitory world ignorant of my reality?/ Rebellion is my aim, Youth is my religion).”

The author is an assistant professor in the department of history, Aligarh Muslim University