Historians think that the ‘Spanish ulcer’ ruined the prospects of Napoleon in Europe, while the ‘Deccan ulcer’ ultimately ruined the Mughal empire under Aurangzeb. Consistent disturbances and unpredictable political turns in these regions were categorized as ulcer wounds that remained open for long, ultimately destroying two powerful rulers in a span of one hundred years in two different continents. Similarly, going by the latest political developments in Kerala, one can observe that a range of recent administrative and political issues, emanating from what Lenin called ‘the bureaucratic ulcer’, have now begun to weaken the prospects of a second term for the Left government in the state. Despite its strong performances in social, medical and educational sectors, unpopular developments in the realm of law and order and police administration have created a deep detachment and suspicion among people and left activists.

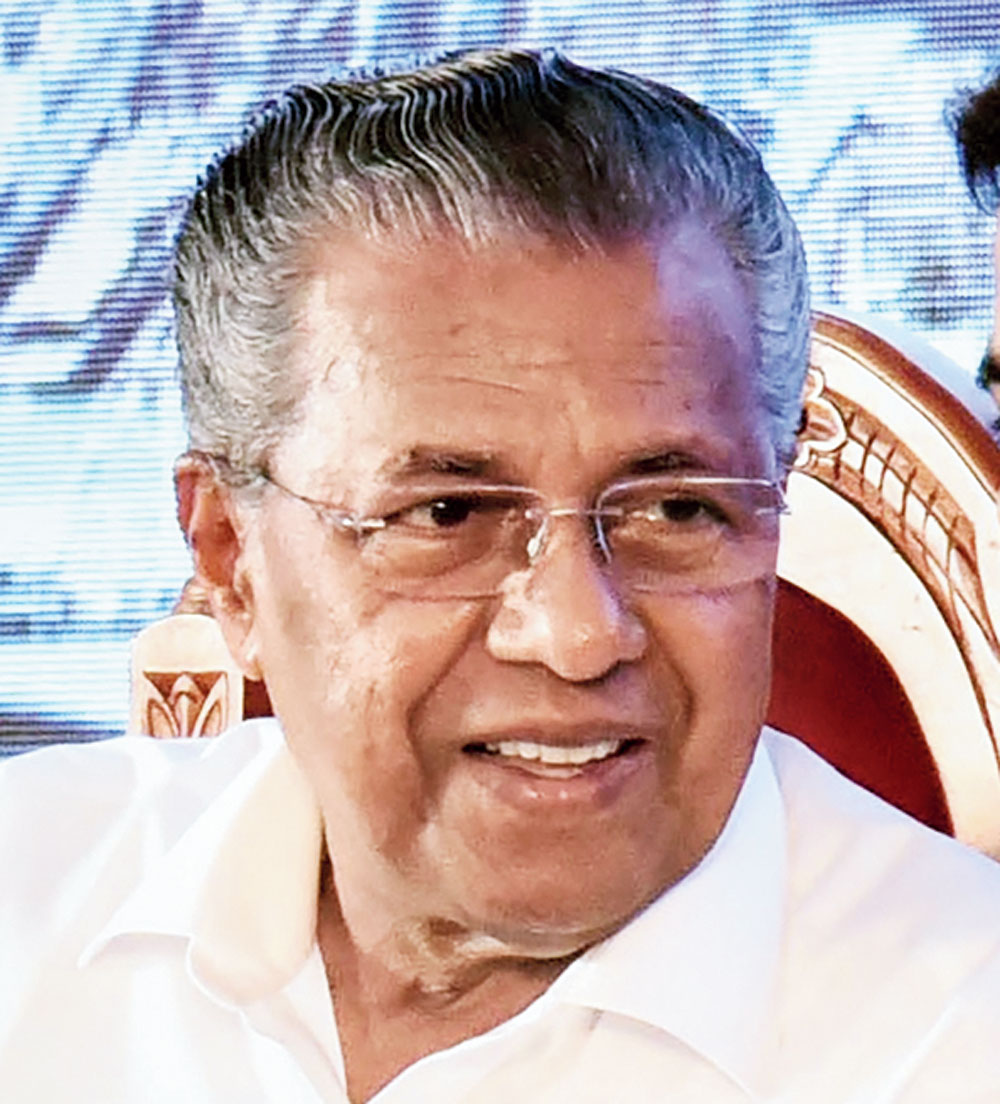

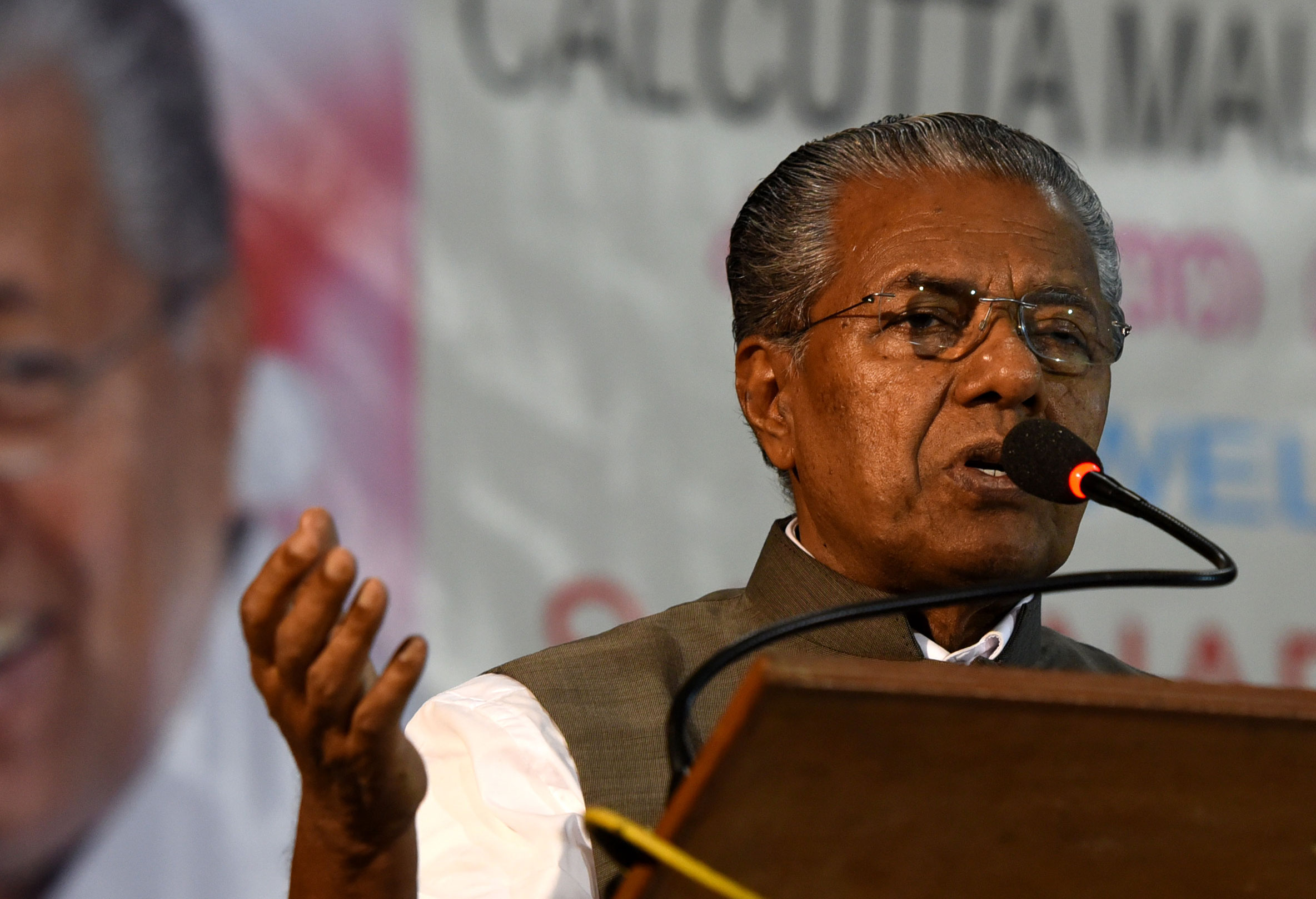

The ‘encounter’ killing of four alleged Maoists (October 29) and the invocation of the provisions of the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act against two members of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) itself (November 2) have unleashed unprecedented anger against the government and its police administration. As the fear of a ‘Deep State’ emerges slowly, the illusions around the Left’s slogan, “Ellam shariyakum (everything will be alright)”, are being eroded gradually, at least in certain significant electoral constituencies. The government under Pinarayi Vijayan has been under fire for its handling of the police administration and the apparent lack of control over the home department.

Civil society collectives and public intellectuals have raised concerns about the police for violating the due process of law and contradicting government policies. The discussions that ensue from the latest political issues are loaded with the opinion that a powerful section in the state police desists from sharing the administrative concerns of the government, apart from consistently embarrassing the ideological framework of the Left in the state. The CPI(M)’s national leaders, including Prakash Karat and Sitaram Yechury, have been very critical of such tendencies and raised questions about the invocation of the UAPA provisions against two young activists of the party. Many state leaders of the party see the whole situation as being symptomatic of ‘unsettling developments’, while other parties like the Congress look at them as a cleverly manufactured situation for obviating discussions on such issues as the ‘PSC scam’.

The encounter killings and the UAPA cases against two party workers have created multiple popular narratives and two of them now shape social media discussions and social imaginations. The more accepted narrative brings up a number of diverse issues over a period of three years since 2016 with a common thread — the state police. These issues include six custodial deaths, seven police encounters, more than 50 UAPA cases from the Malabar region, mob lynching of an adivasi youth and the recent acquittal of the four accused in the ‘Walayar rape’- and-death case. In this case, the police had been accused of diluting the Pocso charges against the accused who allegedly raped two minor sisters from a Dalit family in 2017.

The dominant narrative tries to show an interesting pattern and identifies most of the affected persons in these cases to be from socially underprivileged communities that have been traditional supporters of the Left. Similarly, by pointing out the tangible shift of Muslims towards the Left in the previous assembly elections, the protagonists of this narrative also ask why the Left has been clueless about a large number of UAPA cases filed in the state after 2016. Even though the internal enquiries conducted by the state police declared the majority of these cases to be unsubstantiable, the increasing fear of being minority has become an untold, but palpable, reality in Kerala.

Extensively circulated through social media platforms, this narrative also indicates the existence of a politically motivated section among law enforcement agencies in Kerala, a fact admitted by the chief minister himself during the Sabarimala issue. In this narrative, this section of the administration seems eager to bust the sense of safety among the religious and ethnic minorities and their confidence in the Left. It opines that the minority identities of the alleged Maoist sympathizers might serve such purposes irrespective of the factual record of the matter. Buyers of this argument also think that this indifferent section has become a bureaucratic ulcer and an instrument of alienation which damages the relations between socially marginalized communities and the Left in Kerala.

The second narrative — it spreads slowly — discusses a generation of youngsters who are unhappy with the ‘failure’ of the Left which, according to this view, offers nothing at the moment to counter Hindutva or neo-liberal economic violence. Considering that the ideological commitment of the Left has been compromised significantly, this generation refutes the ability of the Left parties to represent marginalized voices. According to this narrative, this generation finds the electoral Left as an unfulfilling dystopia that refuses to rejuvenate its ideological premises that got trapped in neo-liberal requirements. Since this generation cannot associate with right-wing politics or hyper-identitarian religious collectives, the radical Left emerges as a viable neo-utopia in the state.

This narrative got strengthened after a couple of mid-level leaders resigned from the CPI(M) in the light of the latest encounter killings and criticisms they generated from disgruntled party activists in the state. “If the long standing activists from loyal ‘party families’ can fall from the grace of senior leadership, what guarantees can the party assure to young activists who do not have such genealogical capital?”, ask the protagonists of this narrative. Although this narrative essentializes the caveat of disgruntlement and presents an imagined community of insidious anti-Christs within the party, the likelihood of such transgressions from a dystopian Left to a neo-utopian Maoism cannot be overlooked.

These two narratives have opened up fertile opportunities for other players in Kerala politics. For Hindutva organizations, the presence of alleged Maoists, who are spotted with identifiable cultural markers like names, gives a momentum to their anti-government protests immediately after the controversy around the Sabarimala temple. Their earlier accusation of Vijayan as a ‘Hindu antagonist’ has now advanced and the new rhetoric locates the CPI(M) as a repository of ‘closet Maoists’ who threaten the peace and the security of the State. Similarly, Islamist fringe groups have begun strengthening their position, which places the Left outside the socially marginalized communities. These groups have unfurled a new front of attack on the CPI(M) so as to reiterate their earlier argument that the Left has been inattentive towards the cause of vulnerable sections — in their words, the ‘victims of permanent denial’.

In all these narratives, the state police force looks like a bureaucratic ulcer. With continuous indifference to the political mandate that the party received in the last assembly elections, this ‘ulcer’ has now evolved sharply into the ‘Achilles heel’, damaging the benefits that the party received from flood management and educational policies. If the Left alliance continues to refuse a considerate retrospection of such issues, the CPI(M)’s new Achilles heel has the potential to affect its chances of returning as the ruling party second time in a row after the next assembly elections.