Two provincial assemblies, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, were dissolved by Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf in January. Caretaker set-ups are in place, but no election date has been given by the governors of both provinces. According to the Constitution of Pakistan, elections have to be held within 90 days of the dissolution of assemblies. The Election Commission of Pakistan had suggested polls in Punjab between April 9 and 13 and elections in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa between April 15 and 17. There were reports that the Pakistan Democratic Movement government wanted elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to be held at the same time as the general elections later this year. However, the Constitution does not say that elections cannot be held separately; which is why observers say the PTI went ahead and dissolved the two assemblies where it was in power so that either elections take place there before the general elections in the country or early general elections take place on the same day. But the way in which the governors of both provinces have delayed announcing a date for the elections has led to a constitutional crisis.

Last month, the president, Arif Alvi, announced April 9 as the date for holding elections in both Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa by exercising his power under Section 57 (1) of the Elections Act, 2017. Legal experts say that Section 57 states that the president has to consult the ECP and cannot announce dates of elections unilaterally. The ECP had excused itself from holding consultations with the president because the matter was ‘sub judice at various judicial fora’.

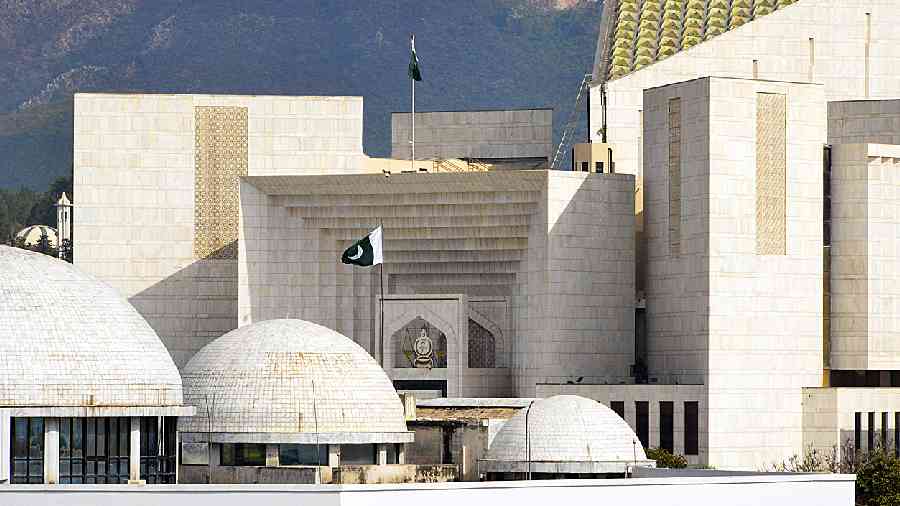

Led by Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial, a larger bench of the Supreme Court is now hearing suo moto proceedings regarding the delay in the announcement of a date for elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. When the nine-member bench was initially formed, a joint note by the Pakistan Peoples Party, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) and the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) had demanded the recusal of the two judges, Justice Ijazul Ahsan and Justice Sayyed Muhammad Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi. The letter said that “it is apparent from the Feb 16, 2023 [order] passed by a two-member bench, comprising Justice Ijazul Ahsan [and] Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi, that they have already disclosed their mind.” Apart from this, legal observers had pointed out that there were alleged audio leaks between Justice Naqvi and the former chief minister of Punjab, Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi, and propriety demands that he should not be part of this bench hearing a political case. The resized or reconstituted bench now has five members sans these two justices and two others who raised questions regarding the dissolution of assemblies and the suo moto notice. The Supreme Court is expected to announce its verdict soon. Legal and political observers say that there is no doubt that elections should take place within 90 days in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, but for the Supreme Court to take suo moto notice in this regard raises questions about institutional boundaries. There is conjecture that this matter should be resolved by the political stakeholders and not by the judiciary. In the last few days, we have seen the PML(N)’s Maryam Nawaz Sharif raise questions about the judiciary’s alleged bias and its past judgments, especially those against her father, Nawaz Sharif.

Recently, some comments made by the Chief Justice sparked a debate in the Upper House — the Senate. While hearing a petition by the PTI chairman, Imran Khan, on February 9, Chief Justice Bandial made comments regarding one honest prime minister in Pakistan’s history, something that was not taken well by parliamentarians. In the Senate, the PML(N) senator, Irfan Siddiqui, wondered who had given the Chief Justice the privilege to call everyone, from Liaquat Ali Khan to Imran Khan, dishonest. He pointed out that parliamentarians never singled out judges and asked if it would be acceptable if someone in Parliament says that only one judge is honest. Pakistan’s judiciary has courted controversy in recent times. For the last few years, Pakistan’s politics has suffered due to various judgments. Now there are ‘admissions’ through journalists from a former chief of how political management took place that helped pave the way for the PTI and Imran Khan to come to power. While the involvement of the Establishment has now been admitted by the institution itself, it would be prudent for the judiciary to also admit its mistakes and undo them, be it its judgment in the Panama case, the lifetime disqualification of politicians or other such decrees. Pakistan and its people have suffered the most in the last few years because of such political management, leading to political chaos and economic crisis.

At the heart of it all is the not-sosmall matter of who gets to rule the country and whether the people’s right to vote matters to anyone in the higher levels of power. If, indeed, Pakistan has had only one honest prime minister, that is a sad state of affairs. It also brings up the much-debated issue of institutional boundaries. The current debate generated by the judiciary’s remarks is, therefore, of significance. The courts have given out their verdicts as per the law of the land and their interpretation of the law. What is necessary is to ensure that the constitutional tenet of the separation of powers is guarded zealously by all institutions. Without this, Pakistan will continue to go through a see-saw of power games. If Parliament is the representative of the will of the people of Pakistan, and its job is to legislate, then the job of the judiciary is to determine whether such legislation is consistent with the norms of the Constitution. For the good of the State, jurisdictional parameters need to be upheld because in an age of perception, each remark and statement runs the risk of being politicised, manipulated, and used by all stakeholders to their advantage. In the case of the judiciary, this becomes even more risky since any perception of bias can only lead to a dilution of the concept of justice, the rule of law, and judicial integrity.

Mehmal Sarfraz is a journalist based in Lahore; mehmal.s@gmail.com