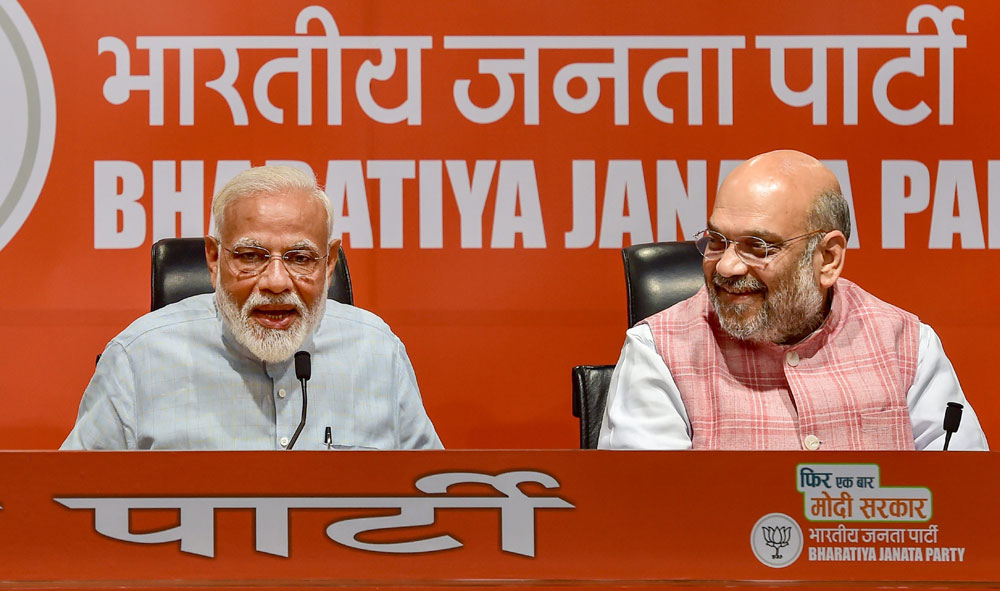

Watching Narendra Modi’s television ‘interviews’ confirmed my suspicion that this is not a medium for our part of the world. Perhaps it isn’t Modi’s fault that the organizers handed him the platform on a platter, but, obviously, he was delighted. Whether or not the Election Commission chooses to take note, each interview meant a blaze of publicity; each question provided a peg on which to hang a long speech while the silent interviewer smiled ingratiatingly and nodded acquiescence.

In the absence of meaningful follow-up questions, Modi set the agenda. There was little pretence of the cut and thrust of interrogation. It’s impossible to imagine any Asian country tolerating something like the historic encounter in 1969 between David Frost and the British Conservative politician, Enoch Powell, who had notoriously warned that unchecked Afro-Asian immigration would mean “rivers of blood” in Britain’s streets. It was a sizzling session with the two men standing up face-to-face at one point, straining at the leash. In an unprecedented move, the channel extended the programme to double its length. Television rating points here can only go up if the fare is similarly packed with exciting action. But would either subject or questioner allow such irreverent candour?

Since the former is by definition a public personality of consequence, it goes without saying that he/she is also arrogant. The latter’s diffidence (his livelihood depends on the media institution that employs him) is compounded by the self-interest that recognizes in the stellar subject a means of rising to greater heights. Unpalatable questions might blight that prospect. People are probably right about the private sector’s corrupting influence but government institutions have much more patronage at their disposal and are better placed to strike a deal with a complaisant media. The journalist who seems bravely to fly the independent media’s colours but is really an influential politician’s fifth column is common enough in our catch-as-catch-can society.

My first experience of a senior politician’s refusal to hold himself publicly answerable for his actions was with the legendary K. Kamaraj who was also the first Indian politician of consequence I met. Kamaraj had just resigned as chief minister of what was still Madras. The famous Kamaraj Plan had yet to be unveiled. Sitting immobile like the Buddha in an armchair in his austere room, Kamaraj received me cordially enough and indicated a chair next to his. Why had he resigned, I asked. To do village work, he said, and revitalize the Congress party’s grassroots support. Quoting from memory after 56 years, I then asked with the brashness of youth if this regeneration was necessary because the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam — not yet quite a household word — was boasting of taking over. “All bluff!” was his curt dismissal. When I persisted with the question, Kamaraj refused to continue the interview. Instead of the famous “Parkalam ... Let’s see,” there was a blunt “I no talk” before I was shown the door.

As it happened, the rumours I had picked up weren’t far-fetched. Kamaraj’s successor, M. Bhaktavatsalam, was the last Congressman. The charismatic C.N. Annadurai, already waiting in the wings, replaced him in 1967. Lee Kuan Yew once heard Annadurai at a public rally in Singapore, and not understanding a word of the DMK leader’s chaste Tamil, was nevertheless entranced by the crowd’s delirium and the knowledge that 40 million people in India (and more in Ceylon) were similarly captivated. Annadurai had cast his spell over both Sparta and Athens, Lee exclaimed in wonder. Tamil Nadu hasn’t looked back since then. As the DMK and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam played Cox and Box, with the Congress nowhere in sight, I wondered if it ever occurred to Kamaraj before he died in his sleep on the 12th anniversary of his resignation that my question which he spurned wasn’t so remote after all.

My more spectacular failure was with Zia-ur Rahman, president of Bangladesh, whom I had met briefly at the 1976 non-aligned nations summit in Colombo, when he was still technically No 2. The formal interview several years later got off to a bad start from the moment Daud Khan Majlis, his affable press adviser, took me into his chamber in Dhaka’s Banga Bhaban. Back from a busy round of canal-digging — his current fetish — Zia was gazing with narcissistic delight at a video of himself as the centrepiece of the day’s doings. Absorbed in the film, he didn’t even realize I was watching him watch himself until he suddenly noticed me, barked an order to Majlis to shut off the video, and turned to me. Barely had I opened my mouth than he snapped a question that had no bearing on India-Bangladesh relations but revealed the cultural complex that might impede them. “Have you been only to convent schools?” he demanded. In Colombo, he had referred enigmatically to “Calcutta Bengalis”. Expanding on the theme, Zia turned to Majlis to mock visiting Indian Bengali diplomats who — so he said — couldn’t speak Bengali.

Irritated, I tried to steer the conversation from the personal to the political, and mentioned infiltrators in Assam. That enraged him even more. Delivering a stern oration about Bangladesh’s booming economy, Zia told me there could be no question of migration to any neighbouring country with a lower standard of living. But he was concerned about occurrences like the Assam disturbances because they imperilled his prosperous nation’s social and political stability. No sooner had he finished lecturing than the door burst open to reveal a young man in military uniform who shot off a stiff memorized spiel in execrable English. I barely followed what he said but realized Zia was being summoned. I am convinced he had pressed a hidden bell to signal the end of that fiasco of an interview. As I scrambled out, Zia loudly ordered Majlis in Bengali to treat me to “a very good cup of coffee”.

Those meetings failed because neither Kamaraj nor Zia would suffer examination. In their culture, politicians ordain and journalists broadcast their wisdom. Tom Wicker, a New York Times reporter, noted that whatever the American president says is news and must be reported. It’s the same with South Asia’s leaders. But if Modi comes across as monarchical, his interlocutors are at least as much to blame. No one told him when he thundered about the heresy of “two prime ministers in Hindustan” that he may not know but every province had a prime minister until 1950. No one forced him to confront his 2014 promises regarding job creation, farmers’ incomes and black money repatriation. Or asked why demonetization hadn’t snuffed out terrorism. Nor was any interviewer courageous enough to mention his bizarre theories regarding genetics and human transplants.

Any political leader who seeks public office in a democracy must face uncomfortable questions. If an adversarial role is not mandatory for the media, neither is the role of courtier. There’s a respectable third position where events and not emotions determine a responsible response. When a veteran Communist Party of India parliamentarian accused me of “inconsistency”, I tried to explain that barring considerations like national security or communal harmony, my consistency lay in trying to deal fairly with the situation in hand, not in serving some person or interest that the situation might affect. That is probably what makes me an uncomfortable participant in discussions with committed panelists and subservient anchors.

Journalists who mobbed the prime minister for a selfie didn’t care about compromising their integrity since they knew they were courting power. It would be more useful if, instead, we could watch people who matter being grilled by incisive interlocutors on matters of public concern. Precise and informed interrogation can bring unsuspected facts to light. Meanwhile, passing off command performances as interviews blurs the distinction between editorial and “advertorial” and should count as campaigning. Many interviewers deserve to be bracketed with election agents.