Sometime in 1959, when I was still in kindergarten, I recollect that my school was closed for an unscheduled period of time. There was violence in the city. My parents would become very agitated after reading newspapers and listening to the radio. I learnt that many poor people were protesting against inadequate food availability, and that the police had killed some of these demonstrators with guns. I still could not imagine how one might have to die a violent death just for asking the government for food. It left an indelible mark on my mind. I also remember a vivid newspaper picture of a public bus burning, having been set on fire. When I asked my parents about who were responsible for setting the fire, I was told that the demonstrators did it out of despair and helplessness. A few years later, somewhere in school I learnt that there was a difference between an ordinary murderer, and a martyr who killed an oppressor, like some of our freedom fighters. In certain circumstances it might be even good to kill a violent person, to prevent him from killing many others. I learnt, too, that the nation state was authorized to kill foreign (enemy) nationals in an arena of war.

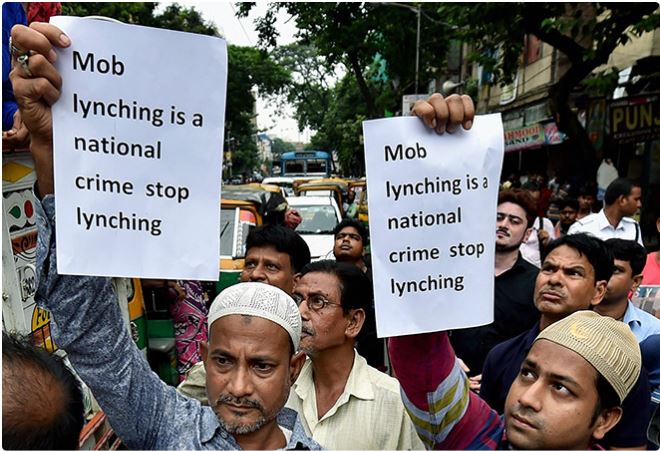

Like most us, I also learned to live with violence all around me. In school I have been beaten up and caned for the flimsiest of reasons: I was taught repeatedly to accept my punishment like a man. The headmaster was authority personified and it was my duty to accept authority without question, although the reason behind this duty was never ever clear to me. In college I saw fellow students talking about a revolution — killing big landlords and policemen. They were fighting for the poorest of the poor. Then I saw the reverse too: police killing students and young people. Sometimes young revolutionaries would be arrested, then released in a vacant place, and then shot dead from behind. The age of encounters had arrived. The adults indulged in a lot of anger and concern about how misguided youths, instead of building careers, chose the path of violence. Now, as a senior citizen, I hear and see continuous news about rapes, assaults, encounters, lynching of members of a particular community — and special murders. These murders were committed not for monetary gains or revenge. They were to shut out voices of people whom someone did not like or agree with.

There are quite a few complicated questions here. I do not have convincing answers to any of them. Is there a difference between killing one or a handful of people, and killing many or even an entire race? The second question is whether there is a difference between killing people and letting them die? Is there a difference between violence by the poor and oppressed, and violence perpetrated by the State? Is there any difference between socialist or communist movements that indulge in violence, and violence conducted by ultra-nationalist groups or fascist movements? In brief, is there a moral code that helps us decide which type of violence to condone, and which to condemn? Or is it that any form of violence is tantamount to coercion, and hence morally unacceptable?

Moral judgments about violence are obviously relative to one’s position in society and one’s belief system or ideology. However, there are some common beliefs about different acts of violence, which are widely held. One, for instance, is the belief that violence by the oppressed has legitimacy since it represents moral outrage about the inequities in the distribution of resources and access to privileges. The State on the other hand, being more privileged and powerful, is expected to find a non-violent negotiating space to try and resolve social problems. The State’s use of violence against its own citizens is seldom condoned, except by those holding political power at that moment. Left-wing violence is often regarded as representing the oppressed, and its end objective is never violence in itself. Fascist violence, on the other hand, is regarded as unacceptable as it is found to be unreasonable: built upon emotional and mythical premises, usually relating to a grand past or an imagined enemy. The killing of one individual usually leads to a situation where the circumstance is investigated, and some motive assigned to the perpetrator of the violence, which might even include self-defence. Communal killings or genocide are never even debated. Such incidents are always treated as unacceptable. They are probed only to fix blame on individuals, as in the case of war crimes. The moral authority behind an act of violence is usually segregated into rational authority and predatory authority, with the latter seldom being condoned on a wide scale. Rational authority might be condoned in some cases when, for instance, a person or persons can be forcibly controlled or even eliminated if they were themselves engaged in predatory violence like killing innocent people in a shopping mall or in a place of worship.

Where does the State come in to all of this? Most of us wish that the State be strict with predators but lenient with the oppressed. However, if the State is found to indulge in, or condone, predatory violence like genocide, communal riots and lynching, then it loses all moral authority to govern. It need not be direct in its condoning; keeping silent about such acts would imply exactly the same thing. The second, more nuanced, case in which the State loses its moral authority is where, instead of killing, the State lets people die. Keeping silent, for instance, on a large number of farmers’ suicides would be a good example from India.

India is not a land of non-violence. The State machinery that maintains internal law and order has increased manifold since Independence, such as the police and various forms of paramilitary forces. All governments of all political parties have contributed to this expansion and used it to their advantage, precisely because they could not control the sporadic challenges thrown against the State by the deprived, as well as by different kinds of vested interests. Poverty, social violence based on caste and class, religious intolerance, and identity politics have all forced the hands of the State. In the last couple of decades, as economic growth has risen alongside shocking inequalities, the biggest source of unskilled employment has come from the growth in the demand for private security services. Finally, political and social violence is very often defended in the public sphere by citing similar acts by the political Opposition. If accused of violence, a political party typically claims that its opposing parties indulge in even greater violence. Hence violence becomes an act of revenge in a never-ending loop. No party is likely to say that in spite of our supporters being hurt, we will not do the same to others. No one is willing to acknowledge the futility of violence. Instead, we have a leader of a national political party heading its West Bengal unit, claiming that if his party came to power they would introduce the Uttar Pradesh government’s ‘model’ of police encounters. What is of deep concern is the growing tendency of the State to indulge in predatory violence, while also tacitly supporting non-State actors indulging in the same.

The Mahatma of non-violence, meanwhile, has been kept confined — as a picture on currency notes. This, too, as is well known by now, can be withdrawn from circulation at a moment’s whim.

The author is former professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta