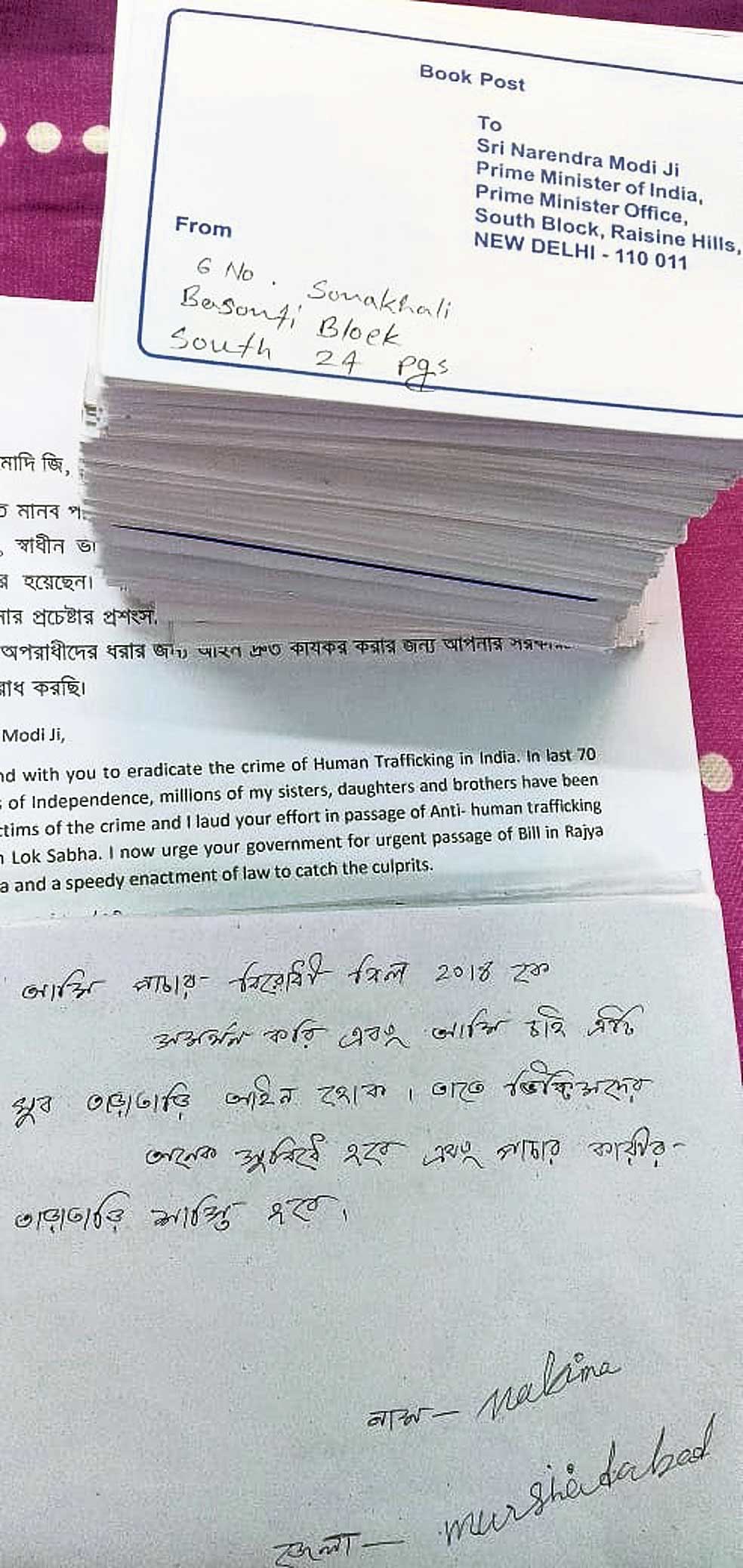

Indian politicians are particularly adept at making ordinary citizens wait indefinitely for legislation protecting their rights. Perhaps that is why the prime minister, Narendra Modi, received around 2,000 postcards from survivors of trafficking and acid attacks asking him to ensure that the anti-human trafficking bill is passed by the Rajya Sabha in the winter session of Parliament. The political inertia that prompted such a deluge of requests is not surprising. It is, after all, on Mr Modi’s watch that India was found by a global survey to be the most dangerous country in the world for women, a section of the population overwhelmingly vulnerable to trafficking. This inertia has, for years, cut across ideological and party lines, thereby allowing serious lacunae to persist in India’s laws on trafficking. If the bill is passed, India will have its first purportedly comprehensive legislation against human trafficking. While this should have happened a long time ago, is there still a case for further scrutiny?

There are a number of reasons to be cautious. Earlier this year, India was found by the global slavery index to have close to eight million victims of modern slavery — to which human trafficking contributes significantly — a number that is set to rise each year given the abysmal rates of conviction. (West Bengal, with the highest number of human trafficking cases in 2016, had a conviction rate of a mere 9.8 per cent.) This is not only because trafficking is a low-risk crime in India — perpetrators fear neither capture nor penal action — but also because existing laws do not focus on protecting and rehabilitating survivors. The new bill is said to be more ‘survivor-centric’, for one of its main provisions is a rehabilitation fund. This rehabilitation, however, must go beyond compensation in the form of monetary assistance and employment. For example, the spaces that survivors will inhabit must be rendered safer, whether these are shelter homes or their own homes. Not only have shelters been shown up as spaces of exploitation — earlier this year, young girls in shelter homes in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh were found to have been subjected to prolonged sexual abuse, mostly at the hands of powerful men — but survivors are also often trafficked, and re-trafficked, by trusted family members. An anti-trafficking law will not succeed in reducing the numbers of women, men and children being exploited for profit, sexually and otherwise, unless it acknowledges all the complexities of deceit, coercion and violence upon which trafficking thrives.