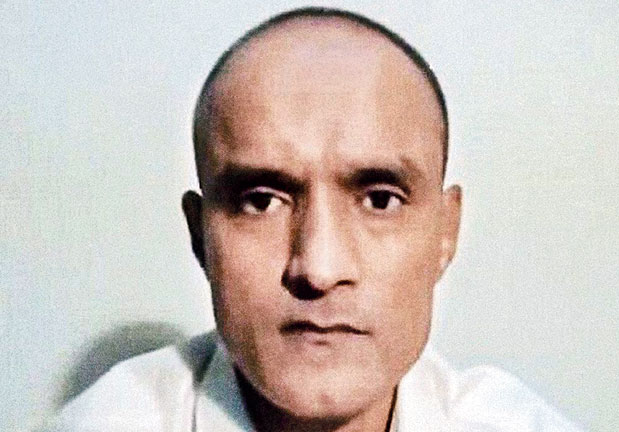

The Kulbhushan Jadhav case began with Pakistan’s arrest and detention in March 2016 of Jadhav, an Indian national. A Pakistani military court sentenced him to death for his alleged involvement in espionage and terrorism. India had requested consular access during Jadhav’s capture, detention and military trial. Pakistan had denied it although it allowed Jadhav’s mother and wife to visit him.

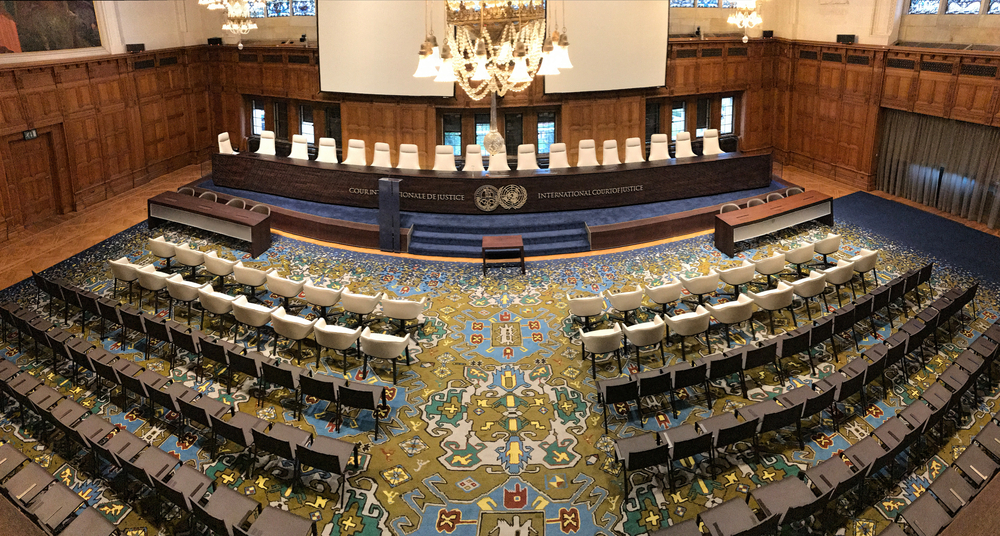

India’s only option to protect its citizen in a foreign country after the denial of consular access vests in the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 1963. Both India and Pakistan are parties to the VCCR and its optional protocol. On May 8, 2017, India decided to knock at the doors of the International Court of Justice. The ICJ obliged India with a provisional measure that said, “Pakistan shall take all measures at its disposal to ensure that Mr. Jadhav is not executed pending the final decision in these proceedings”. Finally, on July 17, the ICJ handed down a decision on the merits of the case.

The ICJ declared that it had jurisdiction in the matter under Article I of the optional protocol to VCCR. The protocol mandates the compulsory settlement of disputes between treaty parties where the VCCR is applicable. Pakistan, naturally, contested the admissibility of India’s application but the ICJ rejected Pakistan’s objection. The court then turned to substantive issues.

The VCCR is a treaty. The rules of treaty interpretations are codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. India is not a party to the VCLT; Pakistan has signed it, but not ratified it. The ICJ, therefore, decided to interpret the VCCR “according to the customary rules of treaty interpretation”. Pakistan argued that charges of espionage allow for an exception to consular access as mandated by Article 36 of the VCCR. The court disagreed. The Agreement on Consular Access between India and Pakistan of 2008 envisages no restrictions on rights guaranteed by VCCR’s Article 36.

The ICJ then broached the breach of VCCR by Pakistan. Pakistan had failed to inform Jadhav of his rights under Article 36, paragraph 1(b). Pakistan did not inform India of Jadhav’s arrest and detention. The court ruled that Indian consular officers be given access to Jadhav so that India could arrange for his legal representation. “Appropriate remedy” for Jadhav, the ICJ contended, would be an “effective review and reconsideration” of the conviction and sentencing by the military court. Respecting the principle of sovereignty, the ICJ has left the choice of means for correcting its breach of obligation to Pakistan. The continued stay of execution, the ICJ said, “constitutes condition for effective review and reconsideration of conviction and sentence of Mr. Jadhav.” Significantly, the ICJ made note of the Rashid vs Pakistan case, a Peshawar High Court ruling, affirming its “legal mandate positively to interfere with decisions of military courts” for bad evidence and “malice of fact and law”. This effectively leaves Jadhav’s fate in the hands of Pakistan’s Supreme Court.

The Jadhav case has brought to light disputed facts. India and Pakistan have disputed the circumstances of Jadhav’s apprehension. India has maintained that Jadhav was kidnapped from Iran; Pakistan argues that Jadhav was arrested in Balochistan, near the border with Iran, after entering Pakistani territory illegally.

The case also exposed the play of optics. An otherwise expensive advocate, Harish Salve, charged a nominal fee of one rupee for a national cause. As the president of the court, the Somalian judge, Abdulqawi Yusuf, pronounced the verdict, the media went berserk, trying to determine which side had claimed victory.

Winning or losing depends on what battles are being fought. The Jadhav case is an example of international arbitration on a dispute that concerns human life.