Economic growth in the recently-ended fiscal year has outstripped all expectations and forecasts. The 7.2% increase in GDP in 2022-23 (FY23), upon 9.1% recorded the previous year, has generated extreme optimism. This is reflected in the near-universal chorus about the economy’s resilience, the resurgence of animal spirits and private investments, a new growth trajectory fired by public spending, reforms, digitalisation and more. It is bolstered further by India’s placement as the fastest-growing major economy in the world by the International Monetary Fund’s projections. The euphoria inspires deeper thinking, an examination of longer trends in the macroeconomy, if only because the antecedents of this strength are unusual — a series of negative macroeconomic shocks over a three-year slowdown, leading up to the pandemic in 2020-21. A look back illuminates the economy’s evolution and provides a perspective as to where it stands at present.

Commentators have flagged that absenting the -5.8% contraction in GDP inflicted by the pandemic in 2020-21 and retaining a steady growth rate of 4-5% in the last three years would imply a 2%-5% higher GDP level (the range reflects different counterfactual rates). This is a crude measure of the slack or the gap that remains to be recouped; alternatively, it represents the permanent loss of output after the pandemic.

Further clues are offered by simple comparisons of three-year averages of key macroeconomic aggregates in FY21-FY23 with the matching pre-pandemic period (2017-18 to 2019-20 or FY18-FY20), a time of continuous deceleration in growth (this had slowed from 8.2% in 2016-17 to 6.8%, 6.5%, and 3.9%, respectively, over FY18-FY20, or up to the pandemic).

Using this gauge, overall GDP growth averages 3.5% in the last three years against 5.7% in the pre-pandemic reference period. Final consumption expenditure, adjusted for inflation, is slower, at 4.5% on average compared to a corresponding pre-pandemic 6.2%, which itself had been a sharp fall from the successive annual growth of 8% before. Fixed assets’ creation has been more stable across the two time periods, with the average growth and share in aggregate output both improving a bit by the public capex support growth in the last three years. What is surprising is that government consumption grew slower on average in the last three years at 1.9%, contrasting poorly with the robust 7.5% three-year average growth recorded before the pandemic.

The biggest difference is made by exports’ growth, an average 11.2% in the last three years and 2.6 times more than before the pandemic. The export stimulation added an average 3 percentage points annually to GDP growth after the pandemic, a significant increase from the single-point contribution before.

A similar appraisal of production or supply-side trends is equally instructive. Features that stand out here are the following: one, manufacturing has grown faster after the pandemic, at an average 5% compared to 3.3% in the reference interval of comparison. This is no doubt closely linked to the robust export growth observed above. Two, the construction segment also increased pace by a similar magnitude (2 percentage points higher), upheld by public investments in the post-pandemic period. Three, the segment of trade, hotels, transport, communication, and broadcasting services displays a steep slowdown. Growth in this segment has averaged a third of that recorded in the pre-pandemic period, a reflection of the harsh incidence of Covid-19 upon services in general. The share of this segment, which is marked by significant informality, has reduced on an average 2 percentage points in the gross value added after the pandemic. In FY23, while GDP accelerated to 7.2%, the share of this category in aggregate output was still one point lower than that in 2019-20. This broadly states the extent of the persisting deficit in the informal economy. A clear offset of this gap is mirrored in the agriculture sector, the fluid counterpart of the informal economy. Agriculture’s share in overall value-added stands enlarged after the pandemic, with a corresponding increase in workers’ engagement in agriculture captured elsewhere by official employment reports.

Altogether, these trends reveal that the pandemic’s economic scars still linger despite the brisk growth recovery. Bear in mind that our reference period of comparison here was itself a time when economic performance was below potential or full capacity. At one level, this enables us to see the distance from those lowered levels. On another plane, our understanding must also factor in the growth support from catch-up demand due to normalisation and the economy’s full reopening last year (FY23). The robust consumer spending of 7.5% annual growth may not be sustained as it was boosted by unspent incomes. Then too, much of this consumption strength is likely to be explained by inequality and asymmetry that have been systematically observed in the recovery period.

The quarterly GDP data display signs of fading demand, the lower tiers pulled down by inflation. In the January-March 2023 quarter, private consumption contracted -3.2% over the previous quarter, slowing down to almost half its rate of growth one year ago. The consumption slowdown is part of a longer trend highlighted above. Joining these dots, including the enduring gap in the major services segments, there’s enough ground for concern about the largest component of India’s domestic demand. It is reinforced by the eventual slowing of the global economy that will undoubtedly impact exports that have dominantly upheld economic growth after the pandemic.

Does the optimism resonate with these macroeconomic trends or appear to be a paradox? How do we make sense of the observed deficits with brightened growth prospects following acutely negative shocks that include a full-blown pandemic and oil price spikes? Other than conclude that catch-up is still some way to go, do future uncertainties induce more caution than confidence? It is easy to get excited at data points but what matters is the trend, which shows us where economic well-being was, and is, at present.

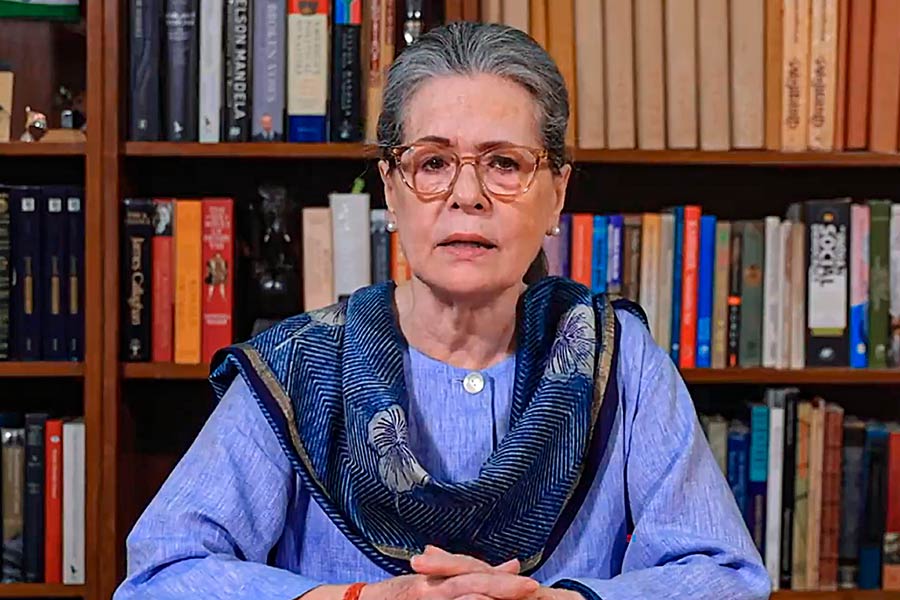

Renu Kohli is an economist with the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, New Delhi