Earlier this week, I was visited by the writer, Aatish Taseer, now based in New York, but who has his feet firmly implanted in the elites of both India and Pakistan. An incisive writer who has landed himself in controversies — some quite needless — he was making a television film on India as seen through the prism of its Muslim minority.

According to Aatish, the mood among India’s Muslims, at least in Uttar Pradesh, was very despondent. In his experience, the Muslim community feels that with the re-election of Narendra Modi, its irrelevance in the present political dispensation has become an established reality. As he saw it, the Muslims believe the worst of the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government and see their position being undermined steadily by the new nationalism that has gripped India.

I don’t believe that Aatish was exaggerating, although he didn’t factor in the divergent experiences of Muslims in other parts of India, notably West Bengal, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala — states where the BJP isn’t in a dominant position. However, since the Muslims of Uttar Pradesh have, for long, set the tone for the entire community nationally, it would be fair to say that the experience in the Hindi heartland is extra significant, at least as far as the media narrative is concerned. By this logic, India’s Muslims are looking ahead to darker days.

The first fear stems from a sense of political marginalization. Ever since Independence, Muslims have quite successfully leveraged their high voter turnout and community solidarity to carve out a special niche in politics. For the first five general elections, the Muslim voters sided with the Congress and in return demanded little apart from some representation in the ministries. However, beginning with the 1977 election after the Emergency, the Muslim vote could no longer be taken for granted by any of the ‘secular’ parties. The Muslim leadership proved adept at bargaining politically at a regional level and even in individual constituencies. Defeating the BJP was undeniably a foremost priority but there were other considerations as well. In Assam, for example, the Muslim community was inclined to support the regional United Minorities Front of Assam in constituencies where the community was dominant and vote for the Congress in seats where broader social alliances ensured victory.

The net outcome of tactical voting was that all the ‘secular’ parties vied with each other for the Muslim vote. This, in turn, fuelled the notion of vote-bank politics. In plain language, this came to mean the exercise of a Muslim veto over issues that were seen to affect the community directly. Thus, the entire issue of Muslim personal law reforms was shelved owing to steadfast opposition from bodies such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board. Likewise, any possible resolution of the contentious mandir-masjid dispute in Ayodhya was jeopardized by the ‘secular’ nudge in favour of judicial procrastination.

This delicate consensus began to show cracks after the BJP emerged as a big player in the 1991 general election. Hesitantly but defiantly, the BJP set about its task of achieving a large measure of Hindu consolidation to offset Muslim bloc voting. In 2014, Narendra Modi achieved what was thought to be near-impossible: winning an outright majority for the BJP without any worthwhile Muslim support. Although explicit Hindu mobilization was avoided, the Modi victory owed almost entirely to a Hindu consolidation effected on other issues. In 2019, Modi repeated this feat even more emphatically with Hindu consolidation being secured through the invocation of nationalism.

The dominant leadership of Muslim communities interpreted the outcomes of 2014 and 2019 as outright defeats. This was rightly so. The BJP not only demonstrated that it was possible to win an election minus any Muslim support but Muslim candidates from ‘secular’ parties found it increasingly difficult to win from constituencies where the community wasn’t numerically preponderant. Muslim representation in Parliament has hit new lows. Indeed, the wariness over fielding Muslim candidates — on the grounds of negative winnability — has now extended to the ‘secular’ parties. Even Mamata Banerjee, who was probably as belligerent as the Samajwadi Party in flaunting her pro-Muslim sympathies, has taken steps to soften her image so that she appears more acceptable to Hindu voters.

The second fear of the Muslim leadership has arisen as a consequence of the ease with which the Modi government secured the passage of the bill to criminalize instant triple talaq, particularly in the Rajya Sabha where the National Democratic Alliance is still short of a majority. The real objection to this move — a follow-up of a Supreme Court judgment declaring triple talaq illegal — lay in the belief that this was the thin end of the wedge. By passing this bill, the Modi government had done something no government had dared since 1939: effect changes in the Muslim personal law. The belief that this bill would herald other overdue changes such as banning polygamy and making the grounds for divorce more gender-sensitive was widespread. I don’t think that a Uniform Civil Code is yet on the anvil — not least because of the unaddressed issues of customary laws in North-eastern India. However, the bogey of a Uniform Civil Code is code for the Muslim orthodoxy’s fear of possible radical changes to the Shariat Act of 1937. Its concern is all the more pertinent because recent events demonstrate the complete breakdown of the consensus that deemed that changes in personal laws must follow demands from within the community.

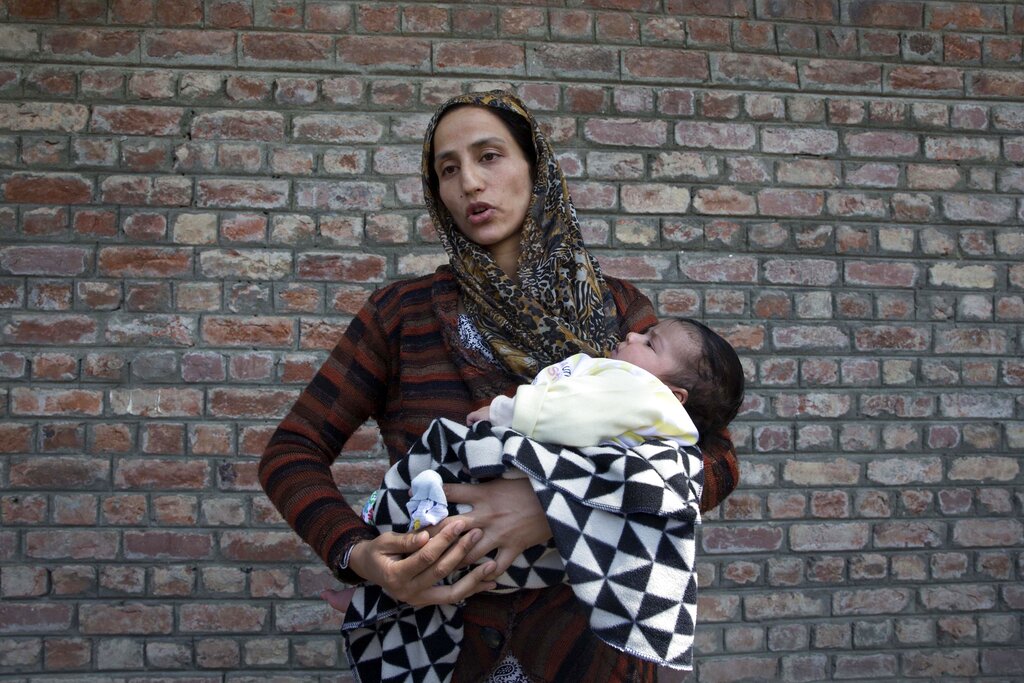

Finally, although the removal of Jammu and Kashmir’s special constitutional status had been a long-standing demand of the BJP, the swiftness of the government action left the Muslim community leadership convinced that its larger political status in India was being renegotiated. Kashmir had so far been projected as an issue of regional autonomy and kashmiriyat. In an abrupt shift, and thanks in no small measure to the posturing of the likes of Asaduddin Owaisi, it was presented as a Hindu drive to undermine the country’s only Muslim-majority province. The moves on J&K were sought to be linked to the larger narrative of the Modi government’s majoritarian impulses. The fears were bolstered by the sharp divisions on Article 370 in the Congress. To the alarmists, it appeared that the entire polity had undergone a profound change after the 2019 elections and had become irrevocably Hinduized.

Many of the fears in the Muslim community are undeniably overstated and tailored to the pre-existing belief that the Modi government is inherently fascist in nature. However, two factors stand out. First, the fears, however misplaced, are nevertheless real; and secondly, the Muslim stakes in the political power structure are more tenuous than ever before. It is the second issue that needs addressing.

In his first speech after re-election, Modi had added sabka vishwas to his sabka saath, sabka vikas approach. This was widely seen as an overture to the minorities that had shunned the BJP in the election. However, apart from a few stray reformists, the response from the Muslim community has been negligible. Nor for the matter has the BJP organized any outreach programmes. Hindus and Muslims may not be battling each other on the streets but neither are they talking to each other. This is not a healthy situation and can trigger an unhealthy move towards greater ghettoization.

Arguably, the traditional Muslim leadership has failed its own community by turning people into voting fodder, thereby engineering a backlash. However, there are as yet no signs of any alternative modern leadership emerging. The trends suggest that it is the Owaisi line of uncompromising but belligerent opposition to the Modi government that is evoking a response from within the community. That is unfortunate and ominous.