June in Guwahati can be oppressively sultry. This is especially so for those who descend upon and halt in this rapidly growing and congested city from other hilly states of the Northeast. It was a particularly hot day in the city when I took an Uber cab to a newly sprung-up exclusive outlet of a well-known international brand of outdoor sports equipment and accessories some distance from my hotel. The cab driver, a caste Hindu Assamese from Mangaldoi, about 70 km from Guwahati, was friendly, frank and talkative.

My driver’s openness emboldened me to ask who he had voted for in the parliamentary elections. Prompt came the reply, “BJP”, in a tone that suggested that it could not have been otherwise. Curious but conscious that it can get sensitive, I was careful not to sound interrogative: “Why?” He did not have a ready answer and fumbled a little before coming out with his best — “They are better than the Congress”. I decide to press on. “What about CAB?” I did not have to expand the acronym of the citizenship amendment bill. Everybody in the Northeast knows what the CAB is. Perhaps my driver would have been confused if I had used the expanded term. “It won’t happen.” His answer now sounded more like a wish. “But the BJP promised to bring it back,” I reminded him. He was silent for a few seconds before answering: “Everything will go up in flames if it does,” unaware of the inherent contradiction in his statements.

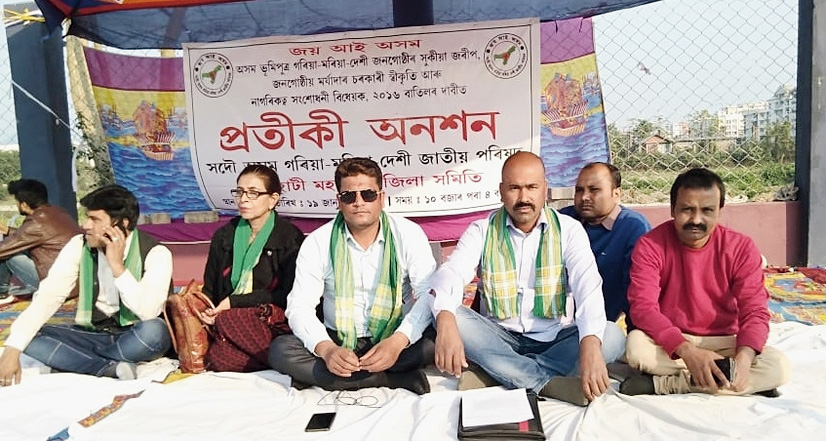

This ambivalence has become a character of politics in the Northeast, more so in Assam. What is evident is a confounding dichotomy between two political undercurrents. On the one hand is the formal, multiparty electoral politics of the Indian system and, on the other, the gut politics that exists at the grass roots, periodically throwing up a combative leadership that thrives on anti-establishment rhetoric.

The first is akin to a carnival and the people are prone to be swept along by the dominant political trends in the country.

The Bharatiya Janata Party is in power at the Centre today, so the direction of the wind in much of the Northeast tilts towards the BJP. But if it is the Congress that is at the Centre tomorrow, the tilt can shift back towards that party. The second political undercurrent is more fundamental, subterranean and constant. It is a more faithful reflection of the vulnerabilities and insecurities of the region. The people’s intuitive defensive responses are conditioned by these weaknesses. These have remained unwavering regardless of which political formation assumes State power.

The two coexist within the same chronological time frame but on different psychological planes. Much like the Guwahati cab driver who voted for the BJP but is opposed to the party’s core agenda, the Northeast electorate seems to embrace this contradiction without any sense of unease. This has been demonstrated many times before, including the manner in which the iconic campaigner against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, Irom Sharmila, was rejected by Manipur’s voters who revile this draconian legislation. This dichotomy is a continuing failure of the larger constitutional politics that is unable or unwilling to sublimate and harness the latter strain into its fold so as to be a truer representative of the soul of the region.

In its last avatar, the BJP-led Central government had pushed the CAB, which seeks to provide non-Muslim illegal immigrants an easier route to Indian citizenship. But Parliament lapsed before the bill had been passed. Back in power now, it is likely to introduce the bill again. A great section of the Northeast is vehemently opposed to the bill but the reason is often misunderstood. It is not against discrimination against Muslim immigrants alone, but against any move to legalize any immigrant group regardless of religious affiliation. This has often been described as inherent xenophobia or reverse racism, but are these labels justified? The response could very well be an expression of self-preservation of marginalized indigenous communities whose languages and cultures are already vulnerable, or even critically endangered, on account of demographic changes brought about by an unregulated inflow of settlers. The legitimacy of the policy response to immigration in the Northeast hence depends on who is answering this question.

Another interesting question follows. The BJP won 14 of the 25 Lok Sabha seats in the Northeast. Does this mean that it has won the Northeast? Given the nature of Northeast politics, the answer is ‘yes’ in form but ‘no’ in substance.