The installation of Netaji’s statue under the imperial canopy near India Gate nudged me into visiting the Central Vista for the first time in many years. I grew up in one of the sarkari colonies near the hexagonal park that encloses the canopy. Many hours of my childhood had been spent cycling past the canopy and down Rajpath, either to borrow books from the British Council library on Rafi Marg or to cycle up the great slope that led up to the Secretariat buildings for the extreme excitement of freewheeling down it again.

I had been reluctant to revisit this childhood place ever since the prime minister had announced its makeover because I didn’t trust his aesthetic judgment and didn’t want my earliest memories tampered with. Most parts of a modern city are transformed over half a century but the Central Vista hadn’t been and there was a certain comfort in that. But in the end,it’s absurd trying to unsee the heart of a city, so on Friday, I drove down to see Netaji newly installed.

Getting there wasn’t easy. The hexagon is, in effect, a giant roundabout surrounded by a massively wide road where the cars never stop. I found a red light near Shahjahan Road that stopped traffic for just long enough to let me jog across. The nearest radial road that led to the canopy was blocked by police barriers; the only way in was via metal detector gates near Rajpath.

There were hundreds of men in fatigues sitting on the lawns and nearly as many civilians who, like me, had come to look at the statue and reclaim the lawns that had been cordoned off for so long. I can report that at this stage of Narendra Modi’s pharaonic project, the vista looks relatively unchanged.The office buildings on either side of Rajpath aren’t visible yet and the underground subways that connect pedestrians to the lawns beyond the hexagon use red sandstone that's consistent with the architecture of the concourse. The fountains work and the shallow rectangular pools that flank Rajpath are blue with clear water.

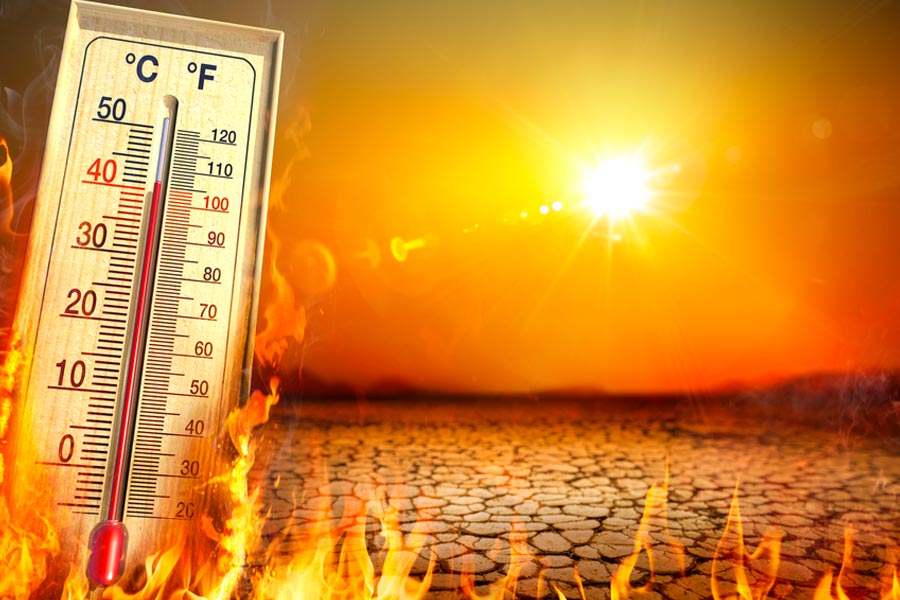

Squinting down Rajpath (it was just past noon and the sun was scorching),the India Gate lawns seemed renovated rather than transformed. It was as if a superior Residents Welfare Association had been given a free hand in fixing the place up and it had done what RWAs do: cordoned it off, expelled the vendors, stopped the maidan cricket and beautified the place by filtering the pools, filtering out the people, and tending the lawns.

The great jamun trees look sick —sparsely leafed and scraggy — which isn’t surprising given that they’ve breathed in construction dust for years now but perhaps they’ll recover once the building is done.

What mightn’t recover is the sense of public ownership that’s always been a special feature of the India Gate lawns. The loafing, ice-cream-eating crowds that filled Rajpath late into the night were unusual for Delhi which, for the most part, is hostile to pedestrian traffic. The India Gate lawns were different; it was almost as if the crowds that filled them up each evening had assimilated this imperial avenue into the republic by making themselves at home.

Till two or three years ago, you could see half-a-dozen cricket matches being played on the C Hexagon’slawns till well into the summer. It was the nearest thing Delhi had to maidan cricket but those greens are now occupied by the Param VirMemorial, the Param Yodha Sthaland the National War Memorial. This is, of course, in addition to the original War Memorial arch that we call India Gate. An imperial vista remade by republican recreation into a public park has now been manicured into a memorial zone that honours military sacrifice. One-sixth of this hexagon used to be a vast children’s park, in keeping with the early republican idea that this colonial vista was now a free resource for its citizens, young and old. This is, I was told, temporarily closed. We shall see if it opens again, or whether it will be repurposed to commemorate martyrdom.

To rename Kingsway and Queensway, Rajpath and Janpath, was a metaphorical masterstroke. Rajpath,the State’s Avenue, met Janpath, the People’s Avenue, and their confluence created the republic. Kartavya Path stands for nothing except the majoritarian’s killjoy need to suppress play— ice-cream eating, picnicking, loafing, cricket — with po-faced invocations of duty.

The first thing to be said about Netaji’s statue is that it is Netaji’s statue. Modi is still constrained by the playbook of anti-colonial nationalism.Given that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s top brass chose quiescence during the freedom struggle, the Bharatiya Janata Party has to spend its time poaching militantly secular patriots like Netaji in a vain bid to repurpose them. Small mercies in Modi’s India are few and far between. Netaji’s statue is one of them; if the sangh parivar weren’t so anxious about its anti-colonial credentials, we might have had a 28-foot Golwalkar or Savarkar in that canopy. We should count our blessings.

The second thing to be said about Netaji’s statue is that it was designed by a committee and you can tell that it was. It’s made of granite of such stygian blackness that all sculptural detail is obscured. For all the 280 metric tonnes of stone that went into its making, it looks like a looming silhouette rather than a three-dimensional sculpture. If you stare really hard at it, you can make out the details of the jodhpurs, the boots, the belted tunic, the cap and the spectacles but they exist as props, unintegrated into a plausible image of this extraordinary man. It’s as if someone made a maquette of a Netaji stereotype and then mechanically scaled it up to 28 feet, making no attempt to achieve that sense of arrested movement that makes portrait sculpture worth looking at.

If Netaji in INA uniform is meant to strengthen our sense of military commemoration, it isn’t clear why he is shown saluting India Gate, a colonial war memorial, with his back to the national war memorial. Why have him saluting, anyway? Shouldn’t this militant leader of the Indian National Army be pictured pointing at Lutyens’ Viceregal palace, now Rashtrapati Bhavan, to remind us that he coined that resounding slogan,“Dilli Chalo”?

And why is he 28 feet tall? We know from the Sardar Patel statue that literal-minded majoritarians believe that bigger is better, but in this case a canopy limits the proportions of the sculpture. The statue of George V that originally occupied that space was set up on a pedestal: the figure itself was much smaller and fitted the space available.Its replacement is so disproportionately large and darkly opaque that Netaji seems trapped in a colonial kiosk.

After George V was removed and exiled to Coronation Park, there was a campaign to instal Gandhiji in the vacated canopy. After many years, a sculpture was commissioned and completed: a sitting Gandhi. It was never used because people saw the problem with installing the Mahatma under an imperial canopy. Some people thought that the vacant space was a good way of signifying the end of the raj. The BJP, which sets little store by subtlety, abhors a vacuum. Luckily for us, it filled that vacant space up with Netaji. It mistook, perhaps, Netaji’s instrumental use of the Axis powers for Golwalkar’s ideological affinity with fascism. Now it’s stuck with a secular colossus overseeing Modi’s Kartavya Path.

(mukulkesavan@hotmail.com)