“We see an extraordinary success story. And we see the remarkable achievements under Prime Minister Modi’s watch that have materially benefitted so many Indian lives,” said the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, at Davos to the journalist, Thomas Friedman, a self-declared “raging Indiaphile”.

Was starry-eyed Blinken referencing India’s rising contribution to illegal immigration in the United States of America? Indian illegal immigrants fleeing joblessness could soon exceed the receding numbers from Mexico. Perhaps Blinken was referring to reports of 7% GDP growth rates. He should know better.

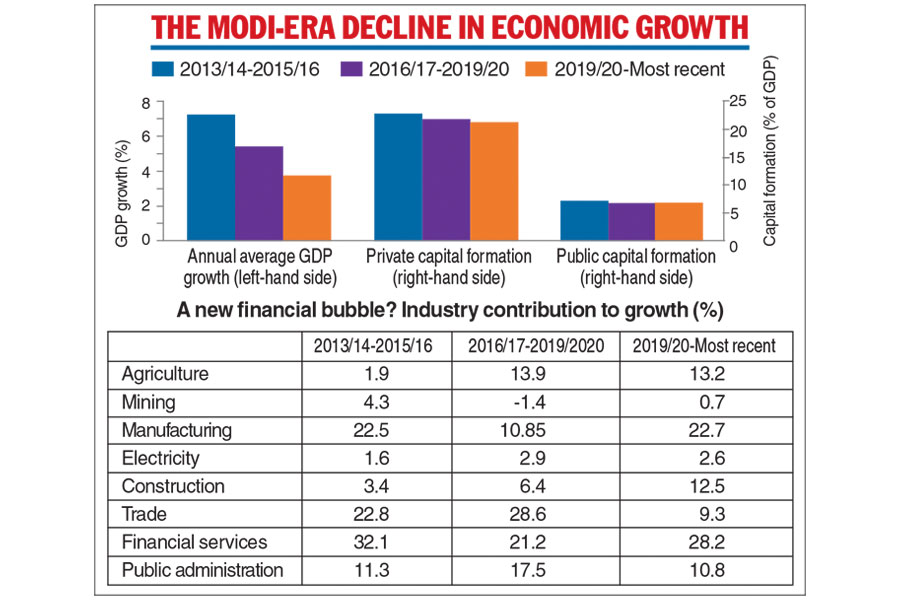

India’s recent growth spurt is a ‘dead-cat bounce’ post its devastating Covid phase. In the entire post-2019 period since the onset of Covid, combining the initial, steep decline with the subsequent recovery, India’s GDP growth averages a modest annual 3.5% rate. Using such multi-year averages is crucial to avoid cherry-picking selective data. India’s celebrated exceptionalism disappears in the clearer vision of averaged numbers. Its post-Covid growth has been lower than that in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and even China amid its extensive economic correction.

The Telegraph graphics

Over the entire Modi era, GDP growth fell from just over 7% a year pre-demonetisation to about 5% following demonetisation and the bursting of an unsustainable credit bubble. And the further fall since then to the 3.5% post-Covid rate is despite being propped up by another credit bubble. The new bubble is corrosive. The government tops up the capital of public sector banks suffering from defaults by big business and banks and ‘fintechs’ push loans on consumers. Fintech loans are often at usurious rates and quickly become unrepayable, causing great stress. Pursuit of mobile loan app defaults by recovery agents have triggered dismissal from jobs, even suicides. Meanwhile, manufacturing growth — the only mass source of dignified jobs — was anaemic even at its high of 1.6% a year; it is now down to 0.8% a year.

Nor are matters improving. Indian business elites talk Modi up but fail to match their words with action. Private investment in machinery and structures (as a share of GDP) continues to decline, a sure sign that Indian investors see the future darkly. Investors have reasons to worry. Their investment has become steadily less productive: a rupee of investment generates ever-smaller increases in GDP.

Two-faced foreign investors singing of India’s brilliant future have pulled back their investment. In the financial year, 2022-2023, the Reserve Bank of India estimates that foreign investment was about $42 billion, which, through ups and downs, is about the same as in 2008-2009, fifteen years ago. Over those fifteen years, foreign investment has come down from about 3.6% to just above 1% of GDP. Foreign direct investment to Vietnam is close to 4.5% of its GDP.

Quite simply, key metrics that the government and its acolytes brandish — GDP growth, manufacturing resurgence, domestic and foreign investment — are, in fact, consistently disheartening. Why is the performance so woeful? The clue lies in the lived reality of the people, especially the jobs and purchasing power they can secure. As Ajit Kumar Ghose, India’s pre-eminent labour-macro economist, documented, the Indian economy employed fewer people in 2018 than in 2012, the two dates with data for assessing the early Modi years. Agriculture and manufacturing jobs fell, while financially precarious construction work and low-end service roles grew. Over this time, about 100 million working-age people, fifteen years or older, left the labour force, joining 400 million others who did not bother looking for a job.

After 2018, the numbers have remained unkind to the assertions of “extraordinary success”. For the 135 million added workers — drawn from the larger working-age population and re-entry of those previously waiting outside the labour market — the economy created just five million formal jobs, those that pay a regular salary and at least one social security benefit.

Instead, given too few urban or industrial jobs, a potentially cataclysmic regression occurred to the agricultural sector. Over half the added workers — many college-educated — piled into agriculture’s most unproductive segments. Having earlier fled that grim living, their post-Covid, non-agricultural options were limited to the small number of jobs in construction and low-end services. Manufacturing continued generating few — mainly informal — jobs.

Is this the measure of success? Today, about 450 million working-age Indians do not work or look for a job. Of the rest, 280 million, 46% of the workforce, struggle in agriculture plagued by declining groundwater and climate crisis-induced stresses that cause heart-breaking crop losses. Unsustainable debt and suicides are common in the vast drylands of western and central India and even in Punjab, India’s breadbasket. In China, 24% and in Vietnam 29% rely on agriculture.

The Indian story gets worse. The entire addition to the agricultural workforce since 2018 comprised the ‘self-employed’, a term that helpless jobseekers use to seek dignity despite their reality of huge unemployed time. Of the self-employed, ‘unpaid household helpers’ accounted for the more than half the increase, mainly women who earlier said they were not in the labour force. Even outside agriculture, most new workers deemed themselves ‘self-employed’.

For Blinken, hyped economic accolades might be good foreign policy, but they deflect attention from urgent Indian priorities. Dignified jobs remain scarce despite the much-touted digital and physical infrastructure. About 85% of Indian school students are functionally illiterate for the international economy, according to Stanford University’s Eric Hanushek. (In China, 14% are functionally illiterate.) The rupee is severely overvalued. Job-generating exports, always weak, are declining. Is it surprising that household consumption — especially of necessities — is increasing so slowly? Is it surprising that the government provides free food grains to 800 million people and pacifies them with more handouts? The hype though must go on, reality be damned.

Ashoka Mody teaches at Princeton University. He is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today