“The Child” (1930) is the only long poem Rabindranath Tagore wrote originally in English. The first draft composed, as legend has it, over the course of a single night, “The Child” was inspired by Rabindranath’s viewing of the Passion Play, first performed in 1634, and put on every ten years since 1680, in the village of Oberammergau, in Bavaria, Germany. The 1930 performance, held on the night of July 20, was watched by many notable figures, including Henry Ford, the British prime minister, James Ramsay MacDonald, Queen Elisabeth of Greece, and Rabindranath himself, not to mention a certain Adolf Hitler (whose name has been discreetly removed from the list of guests in the official website of the Oberammergau Passion Play). “The Child”, written as the shadows of fascism grew darker over Europe, begins with the words, “‘What of the night?’ they ask./ No answer comes./ For the blind Time gropes in a maze and knows not its path or purpose./ The darkness in the valley stares like the dead eye-sockets of a giant,/ the clouds like a nightmare oppress the sky... ” and then goes on to describe a tormented humanity’s journey (“pilgrimage” in Rabindranath’s rendering) to find succour and relief from a civilization that teeters on the verge of total collapse. Rabindranath would later translate “The Child” into Bengali as “Sishutirtha”, whose opening lines (“‘Raat koto holo?’/Uttor mele naa”) were immortalized on celluloid by Ritwik Ghatak in his Subarnarekha (1962, released 1965).

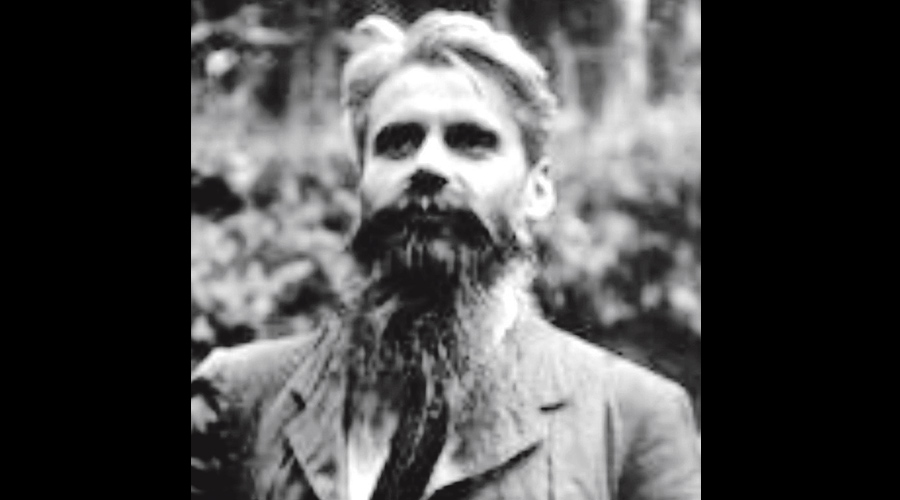

A few days after watching the performance, Rabindranath went to visit a new kind of school — the Odenwaldschule — run by a remarkable German couple, Edith and Paul Geheeb, not far from Oberammergau. In fact, the first draft of “The Child” was written on stationery provided by the Geheebs’ school. Paul Geheeb (1870-1961) and his wife, Edith (née Cassirer, 1885-1982), were part of the New Education Movement that grew out of the New Education Fellowship, founded in 1921 by the British Theosophist, Beatrice Ensor (1885-1974), a loose-knit organization that supported progressive new education initiatives in Europe and North America following the horrors of the First World War. It was the New Education Movement that first exposed the Geheebs to Indian philosophy and educational thinking, and it was probably here that they first came to learn of the educational experiments being carried out by the renowned Indian poet in a remote area of Bengal.

There were many similarities between the education philosophies of the Geheebs and Rabindranath, but the full extent of the mutual exchanges that took place between them have not been adequately recorded and analysed — until now. Fortunately for those interested in such matters, the noted scholar, Martin Kämpchen, puts this right in his 2020 book, Indo-German Exchanges in Education: Rabindranath Tagore Meets Paul and Edith Geheeb. Comprehensively and meticulously researched, making use of archival material from India, Germany, and Switzerland (where the Geheebs had to relocate in 1934, following the rise of Nazism in Germany), and providing many insights and interpretations into the work of the Geheebs and Rabindranath, Kämpchen’s work bears testimony to times and places far removed by geography and history but bound together in trying to seek a new vision of education that would lead to greater understanding among individuals, countries, and cultures. For both the Geheebs and Rabindranath, any education worth the name had to put the child — the pupil — at the centre, seeing each student as a unique human being, not straitjacketing every individual into the same rigorously constrictive mould. As Paul Geheeb put it after the fateful meeting of 1930, “Psychologically, it is certainly interesting that Shantiniketan [sic] and the Odenwaldschule developed totally independent from each other, not knowing of each other for many years, until gradually numerous students and friends of Tagore stayed with us in the Odenwald and praised our school as the Shantiniketan of the Occident.”

After being forced to relocate to Switzerland, the Geheebs set up the Ecole d’Humanité (‘School of Humanity’) in the highlands near Bern, where the experiments first begun in the Odenwaldschule continued to flourish. The similarities and continuities between the two schools were summed up by Martin Näf, in his 2006 book on the Geheebs, translated and quoted by Kämpchen thus: “The Odenwaldschule and Tagore’s foundation, which are so far away from each other, are in a way the expression of a deep communality (Gemeinsamkeit) of emotion and thought, stripped of all cultural differences. Tagore’s language was different from Geheeb’s, it was freer, more radical, more emotional. But Tagore’s yearning for a world beyond the constraints of civilization and for a liberated education… is possibly more akin to Geheeb than any other educator whom Geheeb met in the course of his life.”

There is a great deal that can be said about the experiments in progressive, humane, education carried out by these remarkable individuals, not just in terms of what they thought and said and wrote, but also in their actual praxis, which is beyond the scope of this brief discussion. However, there are aspects to the work carried out in the Geheebs’ schools and in Santiniketan-Sriniketan that bear thinking about as a new national policy is gradually imposed across the educational terrain of our country. The clear focus on the recipients (and not just the deliverers) of education; the emphasis on cooperation (and not just competition); the conviction that there is much to learn from nature and natural processes (and not just in order to score high marks in biology or zoology); the creation of pedagogic models that borrow freely from diverse cultures (without asserting the superiority of one over the other); the emphasis on simplicity and clarity (of both thought and practice) being just some of them.

Martin Kämpchen’s book, though it does not say so explicitly, reminds us that it is all very well to harp on rankings, scores, and grades for individuals (students, teachers) as well as for institutions, making grants and facilities dependent on models using standardized metrics and indices, but, as Rabindranath wrote in a letter to his friend, Paul Geheeb, “[t]he only hope of saving civilization is through ‘enlightened’ education.” Perhaps it is time for all of us to give some serious thought to the true worth of education in the real sense of the word.

Samantak Das is professor of Comparative Literature and pro-vice-chancellor, Jadavpur University.

Views expressed are personal