The most recent round of polls has established again that elections are not won by paying heed to issues that civil society and sections of the media like to rant about. Hate speech is not a strict no-no for political actors; members of minority communities and the media can be regularly attacked without their garnering huge public sympathy. Voters do not worry about the niceties of opaque electoral bond schemes, or the setting up of PM-Cares funds that are not subject to right-to-information scrutiny, or of controversial laws being pushed through Parliament without adequate discussion.

Not only is the media not the political player it was at some periods of our history but it is also a frequent victim. There are attacks every week in some part of the country. Earlier this month, journalists who were on assignment to cover the Hindu Mahapanchayat in New Delhi’s Burari ground were assaulted by Hindutva groups; three were arrested in UP for reporting the leak of a Class XII English paper; a reporter was allegedly tortured in custody in Agra; and a local journalist was among those stripped and humiliated in Madhya Pradesh

for their reporting on a BJP MP and his son.

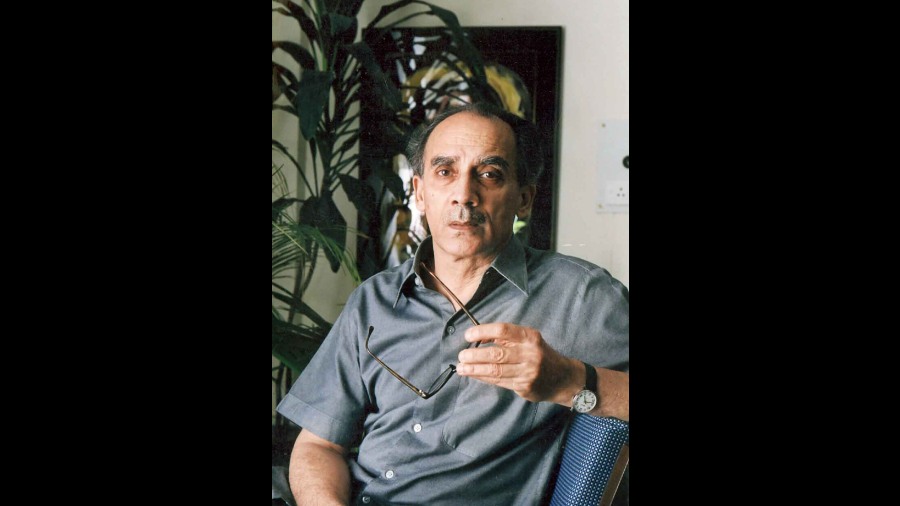

At a time when few have illusions about the might of the press today in India, along comes Arun Shourie’s tome on his years at The Indian Express in two separate stretches, ranging from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. The Commissioner for Lost Causes is a colourful account of the battles the newspaper waged not just on civil liberties issues but also as a political player. In Shourie’s recounting, he and his proprietor, Ramnath Goenka, were tireless interlocutors for actors ranging from the president of the country to Supreme Court judges to would-be prime ministers contending with rival aspirants. Goenka lent the services of his paper and editor to the political Opposition when the Congress was ruling.

Shourie as editor recalls allying with opponents to put the government of the day on the mat. When Ram Jethmalani began asking the Rajiv Gandhi government 10 questions a day, Shourie says the paper began to print these questions, a series which became hugely popular. It helped build Jethmalani’s prominence to a point where he began to think he might make a better prime minister than Gandhi. Shourie describes Goenka egging him on and then telling his editor behind Jethmalani’s back that he would throw him (Shourie) down from the 25th floor of the building if he put Goenka’s paper at the service of such vanities.

Shourie’s was a style of journalism that would raise anxious questions in today’s journalism schools about ‘activism’. It did not bother an editor who saw journalism as a means to an end. Shourie was happy to be an activist whether the reporting was on politics or on what he perceived as social evils. In 1987, when a young woman in Rajasthan called Roop Kanwar was reported to have committed sati on her husband’s funeral pyre, the social activist, Swami Agnivesh, led a march to the site and The Indian Express covered the march and his speeches along the way. Shourie says he addressed a public meeting at a traffic circle along with Swami Agnivesh. There were no bland notions of journalistic proprietary in that era.

(The sequel was Ramnath Goenka summoning him to tell him that the incident had other dimensions, and that a friend had invited him to make a pilgrimage with him to a site where such a great thing had happened.)

Shekhar Gupta, the editor of The Print, asked Shourie in an interview ‘you dealt with the Congress establishment, the VP Singh establishment and also your own establishment (meaning the paper’s owner). What is the difference today?’ Shourie replied, today it is one establishment unlike the days of the media versus politician versus Opposition.

Which brings one to the current relationship between press and politics. For that one needs to turn to another recent book, Aakar Patel’s Price of the Modi Years, which devotes a chapter to the ‘Godi Media’. It describes the shift towards majoritarianism in print media and on television, a process which he says accelerated after 2014. He describes the process as watching television news channels becoming steadily deranged. Historically, he says, the English press had been to the left of its reader.

His documentation bears out Shourie’s point about there being only one establishment today, which the media has increasingly opted to become a part of. With no Ramnath Goenka to lead the charge, today’s proprietors are not heard from even as their journalists are being harassed and attacked. You could argue that the current state of affairs in the country warrants many campaigns, but where are the proprietors to back these? Patel documents the fate of hate-speech trackers that began at the Hindustan Times and at India Spend.

Denial of advertising is being used to bring the press to heel. The Union government is the country’s largest advertiser. When Covid hit newspaper circulation, it only increased the print media’s dependence on government advertising. The Indian Newspaper Society wrote to the prime minister asking for a stimulus package, no less. In return you would naturally be expected to play ball. When the Chinese intrusion took place, the Prime Minister’s Office distributed talking points to journalists whose text one of them tweeted. It included such points as India stands solidly behind the prime minister, the Congress’s efforts to create wedges trashed by other parties, China hasn’t pulled back, China has been pushed back by a united nation led by a leader who led from the front and so on. Patel then goes on to document the television debates that followed such helpful hints.

Patel is described in the book as being chairman of Amnesty International. He describes what happened when the Enforcement Directorate decided to investigate this organization. He writes that he was not shown the charges against him and the organization but they were given to Arnab Goswami of Republic TV to read out on his news show. Television channels were also given talking points on Amnesty India, he says. (Last week, the Central Bureau of Investigation announced it would prosecute Amnesty International and Patel.)

Media activism then is alive and well under the current political dispensation. It has acquired a different colour. You only have to scan the topics of the television debates that he documents, featured by mainstream channels, to get the picture.

(Sevanti Ninan is a media commentator and was the founder-editor of TheHoot.org)