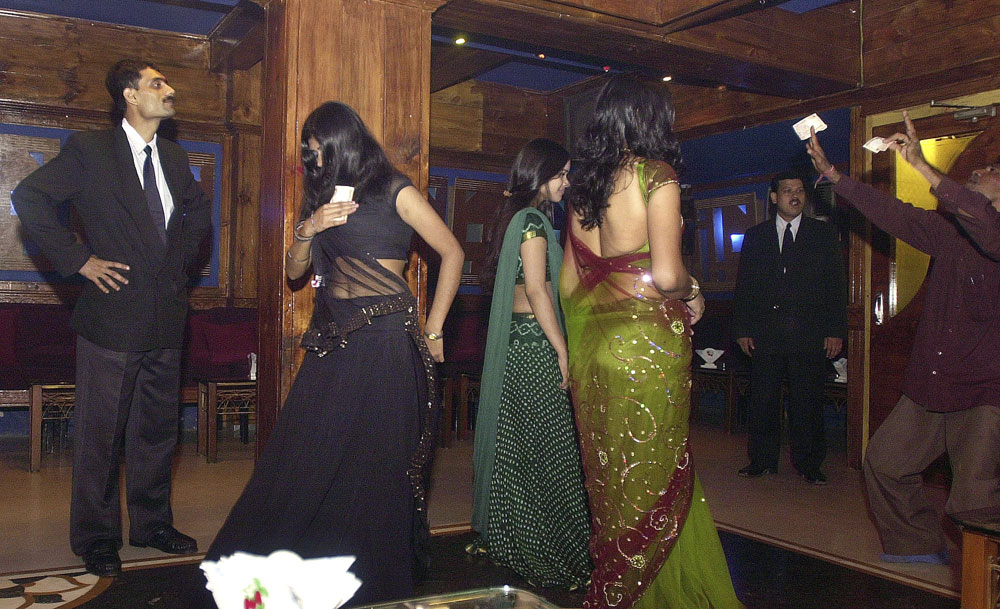

A step out of time — this is how the Supreme Court described the ban on dance bars in Maharashtra. Yet, the state is mulling a review petition of the judgment, which set aside most of the provisions of the ban, noting that standards of morality in a society change with time. What does not change, evidently, are the double standards of society and its institutions. Successive governments have portrayed the bar dancer as ‘immoral’, a woman who shirks honest labour and seduces hapless men. From prostitution to wrecking marriage — that hallowed institution — countless charges have been laid at her door. A majority of these are unsubstantiated, and the courts have pointed this out many times. Conversely, the patrons — usually men — consumers of the performance and, in many cases, exploiters of the dancers, have conveniently been depicted as those in need of the State’s protection in the public discourse. The palpable anxiety is not fuelled by a misplaced sense of morality only. Having lost their traditional sources of support, bar dancers — many of them hail from dancing communities and belong to lower castes — relied on emerging spaces of employment within a liberalized economy to sustain themselves. Their economic rehabilitation, it is believed, threatened entrenched caste and gender equations. Does this potential realignment lie at the heart of the moral indignation? Is the sanitization of the devadasi tradition informed by a similar urgency on the part of the influential castes? Strangely, the practice of offering women to temples — reported to be still prevalent — has been spared such scrutiny.

The ban on dance bars, struck down by the court, robbed willing performers of livelihood and forced many of them into prostitution. Further, like other kinds of prohibition, the ban only managed to push the business underground, its clandestine nature leaving women — whose “dignity” the State is claiming to defend — more vulnerable to abuse. The State’s puritanism regarding the alleged commodification of women has been roundly criticized by activists. The matter is not that simple; several women take up the profession on their own accord, pitting the question of individual choice against the morality of the collective. Dance bars, when allowed to function in an unregulated manner, can impair both law and women’s safety. But a ban is not the solution. Framing better regulations in consultation with all stakeholders can be remunerative for the women and the State. Maharashtra earned Rs 3,000 crore annually from dance bars before the ban in 2005.