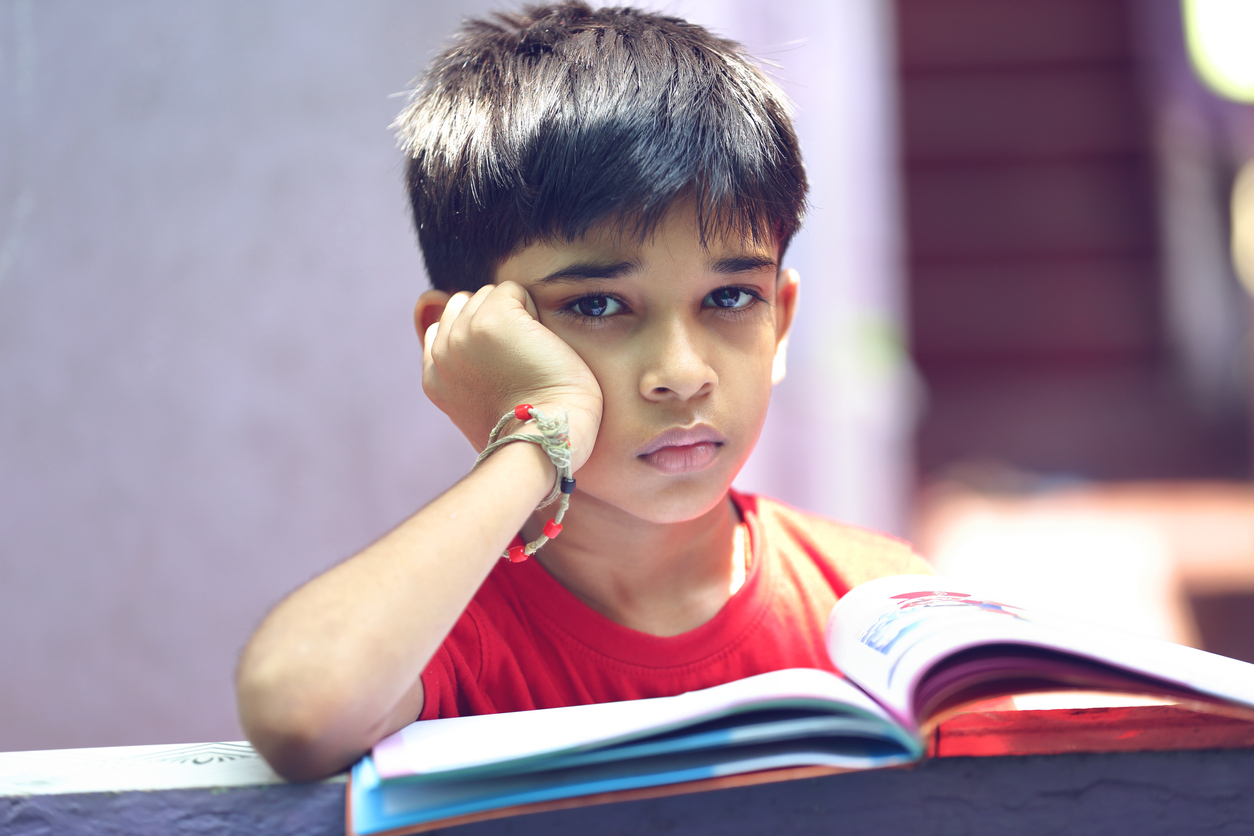

A distinctive marker of Indian culture is its barely-concealed ill-treatment of children. Their safety and well-being are so low on the list of priorities for State and society that the highest court of the land was recently compelled to put its foot down. The Supreme Court, livid over the institutional apathy towards the safety of children in government-run shelter homes in Bihar, ordered the transfer of the Muzaffarpur shelter home sexual assault case — in which over 30 girls, some as young as seven, were drugged and raped by the accused, including the politically-connected owner of the shelter and his staff, over a prolonged period of time — from Patna to a court in Delhi. It also admonished the Bihar government for providing incomplete details about the status of shelter homes in the state. The apex court’s disapproval is justified; this is not the first time that such institutionalized indifference has been revealed. The results of two surveys — one conducted in 2016-17, the other in March last year — showed a difference of two lakh in the number of children living in government-run shelters across India. The possible implications of these figures are worrying. Have two lakh children gone missing? Or are the shelter homes deliberately projecting hiked numbers in the hope of getting more money? The transfer of the case also shows that the apex court lacks confidence in the systems of care for children and the State machinery’s commitment to the investigative processes. Given the lack of transparency, it is no wonder that the court believed it was “in the interests of justice” to transfer the Muzaffarpur trial.

These developments reveal the fundamental problem that allows such criminal apathy to persist: the closed nature of institutions such as shelter homes, especially those for women and children. Their opacity encourages the absence of monitoring and ensures that they are rife with violence, sexual and otherwise. As such, the apex court’s unequivocal condemnation is welcome. The next logical step would be to widen the scope of the enquiry to include other closed spaces where different kinds of transgression, including corporal punishment, continue. A report found that inmates of childcare homes across India are regularly subjected to beatings and verbal abuse, and denied food and basic amenities. The court has clearly indicated the direction in which child protection and care in the country must go. But such change will not be possible without both State and society taking a long, hard look at their skewed values.