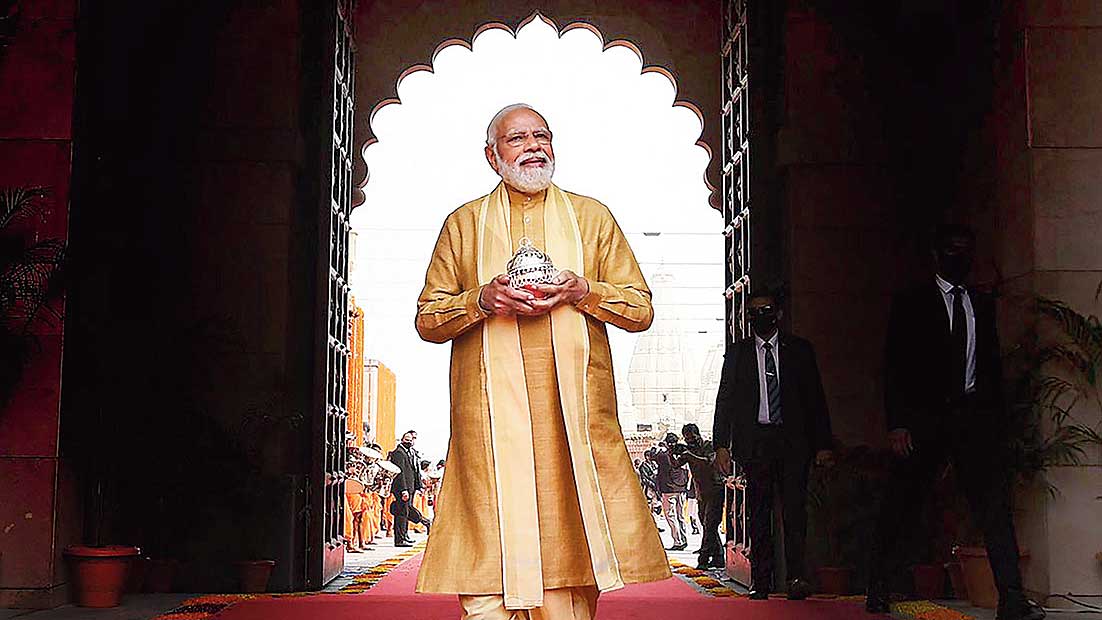

On December 13, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Kashi Vishwanath corridor that created an uncluttered path from the 241-year-old temple at the heart of Varanasi to the river Ganga. It was a project many had considered fanciful since it involved remodelling a part of Varanasi dotted with a warren of narrow lanes and by-lanes. Its sheer audacity was breathtaking, and its national impact huge.

At the inauguration, Modi spoke of the coming together of virasat (heritage) and vikas (progress), a theme that had a special resonance in a city that people have regarded as both eternal and unchanging. He linked the exercise to national self-confidence: “The long period of slavery broke our self-confidence in such a way that we lost faith in our own creation. Today, from this 1,000-year-old Kashi. I call upon every countryman — create with full confidence, innovate…”

Restoring national self-confidence and building a New India that will involve linking a grand Ram temple in Ayodhya and a renovated shrine in Badrinath to universal healthcare and space missions have been themes Modi has touched upon earlier. These, however, have special meanings in the context of Varanasi.

Varanasi or, more precisely, Kashi, has, since antiquity, had a remarkable hold on the imagination of Hindus. Historians may differ over exactly when Kashikshetra — the sacred space on the banks of the river Ganga — became so important in the ritual life of Hindus or whether it is right to include the Buddhist centre at nearby Sarnath as an integral part of the traditional Kashi panchkroshi, considering that it was re-discovered by the British archaeologist, Alexander Cunningham, as late as 1837. There may also be legitimate grounds to quibble over the pre-eminence attached to the lingam at the Vishweshwur (Vishwanath) temple when pre-Islamic texts indicated the centrality of the Manikarnika ghat — now used as a cremation ground. However, regardless of the shifting contours of the sacred space and the rejigging of the wider pilgrimage route, the exceptional importance of Kashi in the Hindu ecosystem is undeniable. It has always been the ‘eternal city’, a place that — in the words of Bholanauth Chunder, the Bengali author of a two-volume travelogue published in 1869 — is “thoroughly Hindoo — from its Hindoo muts and mundeers, its Hindoo idols and emblems of worship... a bona fide Hindoo town, distinguished by its peculiarities from all other towns upon the earth.”

Apart from faith and devotion, the story of Kashi is also inextricably linked with India’s troubled history. Despite contemporary attempts that suggest the Indo-Islamic encounter led to a happy syncretic blend, the Varanasi experience indicates a more contested reality. Nor is this a recent phenomenon. Referring to the Dharhara Masjid — built by Aurangzeb after demolishing the Vaishnavite Beni Madhab temple — whose imposing minarets once dominated the view from the waterfront, Chunder was outraged. He described it as “a blot upon the snow-white purity of Hindooism. It cannot fail to be regarded by the Hindoos as a grim ogre which obtrudes its mitred head high above everything else and looks down with scorn — gloating in a triumphant exultation.” In a similar vein, Enugula Veeraswamy from Madras, who visited the city in 1831, tempered his admiration for the architecture of the Dharhara mosque with the acknowledgment that, in the context of Varanasi, it was a symbol of crude Islamic iconoclasm.

The misgivings over apparently incongruous minarets in a place dominated by shikhara forms were, however, minor, compared to the gaping wound in the Hindu psyche left by Aurangzeb’s demolition of the Vishwanath temple and its substitution by the Gyanvapi mosque. To rub home the humiliation, the Moghuls left a small section of the temple ruins intact as a permanent reminder to the Hindus of their subordination. However, despite the demolition, the precinct around the Gyanvapi — and particularly the old well — remained an important part of the Kashi pilgrimage, and this often led to communal friction. At present, ugly iron barricades and heavy police presence ensures peace.

Aurangzeb’s hurtful demolitions were the second wave of vandalism that Kashi was subjected to. Local legend suggests that the first Vishweshwur temple — said to have been located at the site of the present Razia Sultan Mosque — was demolished in the early years of the Delhi Sultanate.

Avenging the Hindu hurt over the demolition of temples has formed an important part of the Hindu nationalist agenda since the time of Shivaji. For nearly 111 years after the demolition by Aurangzeb in 1669, Kashi was without its most sacred shrine, although in 1700 Sawai Jai Singh II had built an Adi Vishweshwur temple close to the Razia Sultan Mosque and the Peshwas had sponsored an Annapurna temple close to Gyanvapi. It was only in 1780 that the pious Ahilyabai Holkar succeeded in building an alternative Vishwanath temple at a site very near the demolished temple.

This was more than an individual Maratha widow’s initiative. It became the new centre of worship in Kashi thanks to the patronage it received from devotees and notables. In 1841, the Bhonsale Raja of Nagpur donated silver to the temple and, earlier, in 1835, Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab sponsored the gilding of the dome with a tonne of gold. In 1828, the dowager, Baiza Bai Scindia, of Gwalior undertook an elaborate construction of a colonnade over the old well adjoining the Gyanvapi, suggesting that in Varanasi at least, collective memory and faith intersect.

Finally, Varanasi was also confronted with questions of urban governance. In Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City (2017), Madhuri Desai noted that the post-19th-century surge in Hindu pride was also accompanied by deep disquiet: “Indian elites continued to confront the reality of a decaying city that they felt lacked suitable institutions, spaces and buildings. An ideal Banaras would be both ancient and modern, a suitable emblem of the past and an impressive city that would showcase a vibrant and contemporary identity. In its current state... it failed to satisfy either desire.”

With a blend of religious pride, a sense of history and public works, Modi has attempted to address the long-felt impulses of Varanasi. The symbolism of the Kashi Vishwanath corridor is colossal.