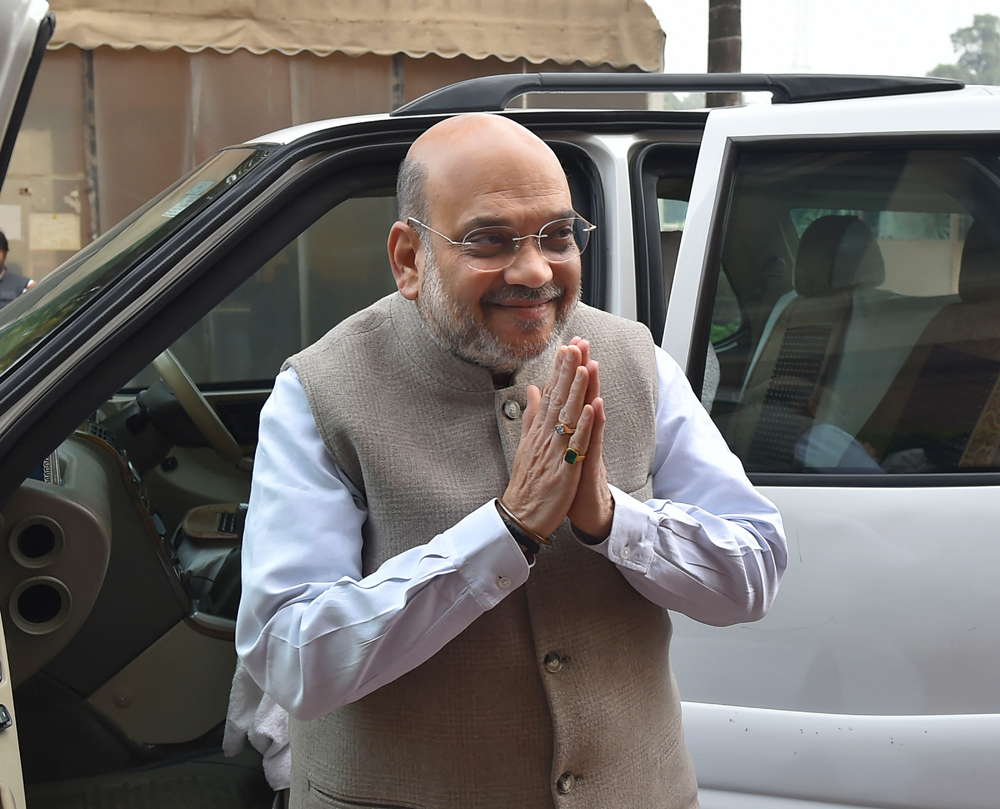

Ever since the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act escalated and covered most of the big cities in India and touched a section of the student population, some of those who are politically committed to the prime minister, Narendra Modi, if not the Bharatiya Janata Party, have been hugely amused by some short videos on social media. Shot at the protest venues, they comprise short clips with some of the more well-heeled participants who have been incensed by the CAA. The interviews are undeniably funny to those who are politically aware. One young girl demanded that the prime minister make arrangements for therapy sessions because she had been so disturbed by the CAA and, presumably the yet-to-be-defined National Register of Citizens, that she had been unable to sleep at night. Another video had another student angrily declaim that the CAA and the NRC were lifted straight out of M.S. Golwalkar’s writings — she even cited the book and the page number — and that this was indicative of the thinking of the home minister, Amit Shah.

It is easy to pick holes in the arguments of these young citizens and even to mock their breathless concerns. Indeed, some of them seemed to be suggesting that the CAA was making the space for the creation of India’s very own concentration camps. However, it is one thing to laugh at the political naïveté of some students and their starry-eyed interpretation of the Indian Constitution. While a quiet smile is irresistible, mockery is unwarranted.

What is important is that many thousands of young students — overwhelmingly Hindu by faith — felt sufficiently motivated to come out into the streets and join demonstrations against the CAA. Their participation was strategically significant. The bulk of the crowds in most of the demonstrations in the big cities comprised Indian Muslims who had been mobilized through traditional networks such as the local mosque. They believed, rightly or wrongly, that the CAA was the first step in the disenfranchisement of Muslims in India, and that a future NRC would be the instrument to take away their nationality and even expel them from India. The young students bought into this misinformation, encouraged largely by activist teachers who had their own distinct agenda, and gave a sectarian protest the character of a broad-based, people’s protest against an insensitive and narrow-minded government. In spite of my own objections to the protests, I can recognize that these young people were driven by motives that appeared noble. Although the numbers were smaller and the middle-aged and elderly among the middle classes stayed away, the student protests were driven by the same impulses that marked the India Against Corruption movement of Anna Hazare in 2013.

The media had played a major role in moulding middle-class opinion against the Manmohan Singh government in 2012-13. Looking back, it is easily comprehensible why the unending revelations of mega scams involving telecom, coal and the Commonwealth Games provoked a mood of disgust and exasperation and had the middle classes rushing to endorse a movement that seemed to be guided by an upright, if somewhat stubborn, Gandhian. The government, which never had convincing answers to the mood of despondency in the country, was further hamstrung by the fact that no one in their right mind could be seen to actually endorse corruption. The only real anxiety over the Anna Hazare movement was its complete disdain for elected representatives and even the institutions of representative democracy.

The students’ movement against the CAA and NRC — one of the two distinct strands of the Opposition — has some similarities with the Anna Hazare movement. Once again, the students seem to be standing up for high ideals — in this case, the basic secular structure of the Constitution — and against a government that seemed unwilling to budge.

However, the similarities end here. Whereas the anti-corruption movement spanned ideologies, the present movement has a definite ideological bias. First, there is a large measure of continuity between the misgivings over Modi’s alleged sectarian vision of India, expressed forcefully on different platforms between 2013 and the general election of 2019, and the present denunciations of the government. The CAA and any future NRC is seen as part of an ideological agenda aimed at excluding Muslims from the nation. Secondly, the movement against the CAA and its supposed attendant features seems quite torn between a vision that sees India as a natural home for all oppressed peoples — including Rohingyas — and a parallel desire to control all illegal immigration indiscriminately. Thirdly, there is a sharp division between those who seek to stop Modi by direct action on the streets and those who believe that India’s parliamentary sovereignty is not absolute and that the judiciary must have the final word on any subject, be it Article 370 or the CAA.

Finally, while the general population and the media have some sympathy for the students who seem to be standing up against a perceived injustice, there is considerable alarm, bordering on fear, at the people who seem to be providing the numbers to the anti-CAA stir. In blunt terms, the movement is seen to be a Muslim revolt against a BJP government that has succeeded in pushing the community to the margins of politics.

In theory, there is absolutely nothing in the CAA that excludes even a single person from citizenship. Indeed, the new Citizenship provisions are not applicable to Indians at all. The discrimination is between those who fled from religious persecution and others who may have crossed the border for economic or other reasons. It is meant for those who have not acquired Indian nationality by birth, descent and naturalization. The Muslim anger seems an explosion of bottled-up frustrations and anger over changes in the community’s personal laws, the removal of Article 370 and the Supreme Court sanction for the Ram temple in Ayodhya.

As of now, the Opposition parties have not been very forthcoming in their views of citizenship. In earlier years, the Congress and the Left parties demanded that Indian citizenship be given to those from neighbouring countries who are ongoing casualties of a population dislocation that began with the Partition of India in 1947 and continued without interruption well after India and Pakistan formalized a visa regime. Syama Prasad Mookerjee was no doubt the most prominent champion of those who got left behind on the wrong side of the Radcliffe Line but there were also others such as Meghnad Saha, Sir Jadunath Sarkar and Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. Many of these demands were echoed during the parliamentary debates on the Citizenship Act, 1955 when Bengali politicians such as N.C. Chatterjee (Hindu Mahasabha), Hiren Mukherjee (Communist Party of India), Renu Chakravarty (CPI) and Satish Samanta (Congress) spoke in favour of giving these unfortunate people Indian citizenship. In West Bengal, the communists in particular were in the forefront of the movement to secure the rights of refugees and its leadership had a disproportionate representation of those who came from Hindu refugee families from East Pakistan. Today, it is ironic that many of these parties are seeking to portray the conferment of Indian citizenship to Bengali Hindus from Bangladesh as part of a sinister saffron agenda aimed at marginalizing Indian Muslims. Today’s Left is outraged that the BJP is even using the films of Ritwik Ghatak on the miserable plight of refugees in the camps to drive home its point.

The wheel, it would seem, has turned a full circle. There was a time when Bengal lamented that independent India hadn’t successfully managed to integrate the legacy of Surya Sen (of the Chittagong armoury raid fame) into its bloodstream. Today the outrage is over the Indian government’s failure to also incorporate the legacy of Ghulam Sarwar (the perpetrator of the infamous Noakhali massacre). I guess that is progress too.