Twenty-one years ago, the artist, Vivan Sundaram, took over the Durbar Hall of the Victoria Memorial to create a massive site-specific installation titled Journey towards Freedom: Modern Bengal, which the artist later changed to History Project. My memories of the installation have faded, but a few vivid vignettes remain, including the words of Ramakrishna Paramhansa, ‘joto mot, toto poth’, translated into English as ‘many views, many paths’, shining in large blue and red neon letters, high on the dome of the Hall; the lush four-poster bed with an incongruous television set showing scenes from the films of Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak; bales of jute with dates and names of historic labour movements written on them; recordings of poems by Rabindranath and Jibanananda; and, most spectacularly, the massive railway track that greeted a visitor to the installation — completely disorienting her/him and setting him/her up for a ‘history lesson’ that called into question received accounts of the freedom struggle in Bengal (and India) and invited the visitor to interrogate her/his own location in that history. Sundaram’s installation did not allow for easy interpretation, which is no doubt why, last year, two decades after the justly-lauded artwork was exhibited, a book on the installation with essays by noted critics and cultural commentators was published, containing pictures, facsimile copies of the artist’s plans and correspondence regarding the project, and, of course, the critics’ analyses of the work.

Thirteen years after History Project, the German installation artist, Gregor Schneider, was invited by the Max Mueller Bhavan to create an installation in Calcutta — for the Durga Puja of the Ekdalia Evergreen Club of Ballygunge. True to his penchant for courting controversy, in It’s All Rheydt (a pun on the name of the artist’s birthplace), Schneider made the façade of the pandal in the shape of a road rising vertically from the actual street where the Puja was located, so that entering the pandal was the equivalent of going below the surface of the road. As a visitor to the Puja remarked, Ma Durga was now living in an underground sewer! Perhaps predictably, Schneider’s work did not seem to find much favour with the massed throngs who flocked to Ekdalia Evergreen.

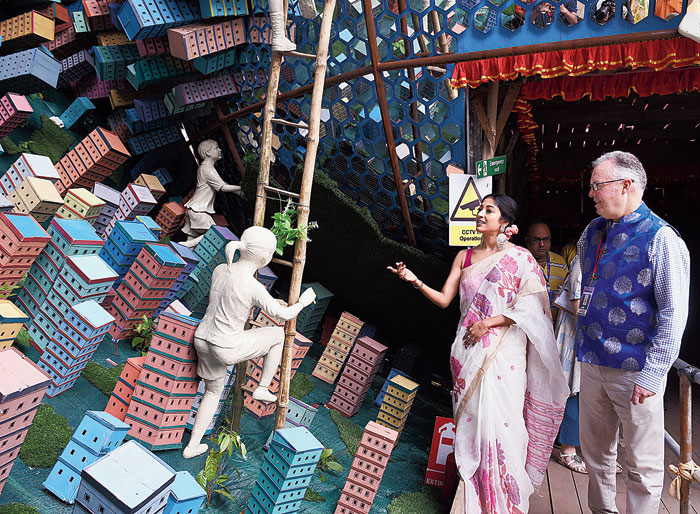

Thoughts of these two installation artworks were prompted by the ‘Theme Pujas’ I visited earlier this month, of which the most thought-provoking was at Samaj Sebi Sangha (picture) on Lake View Road whose focus was on ‘labour’. The path leading to the pandal was made to resemble the buildings, shops, and rooms in which labourers — artisans as well as factory workers — have lived and worked in the city, and where many continue to do so. The line of banians (undershirts) strung high above on ropes, the cramped living quarters with faded pictures of film stars and graffiti, the posters and advertisements on the walls, the rusty trunks, soiled implements, and dented utensils… all of these served to create an effect that was no less than that achieved by the best installation art. The whole ensemble had been designed to recreate the seedy claustrophobia of workers’ spaces (work as well as living areas) — and with the Puja crowds jostling and pushing as one tried to get a glimpse of the idol, this sense of being constantly harried and rushed and pushed by forces over which one had no control (the lot of workers the world over) spawned an experience the likes of which one seldom encounters in a Puja mandap.

Tapati Guha-Thakurta suggests in her magisterial study, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata, that there is often a disjuncture between the glitzy, grand, even phantasmagoric, Theme Pujas and the inevitably shabby neighbourhoods in which they are situated — the genius of Samaj Sebi, however, lay in the way in which the Puja seemed to rise seamlessly from its immediate surroundings, so much so that it was difficult to make out, especially at night, if the shops were part of the neighbourhood, or had been created specifically for the Puja.

Can Durga Puja, and the creative efflorescence it brings forth, be viewed as ‘art’ at all? The simple fact that the experience of Durga Puja can recall encounters with Sundaram’s or Schneider’s work (which are unquestionably, self-consciously, art) raises some interesting questions. Many of these Theme Pujas display the kind of unified sensibility that we, typically, associate with a single artist’s vision, and while some established artists have entered the field of Durga Puja design — the name of Sanatan Dinda comes most readily to mind — others, like Samaj Sebi, apparently, lack individual authors. I went back to Samaj Sebi a day after dashami and looked around for the name of the person who had conceived of such a marvellous work, but all I could find was a painted board paying tribute to workers with fifteen first names listed as ‘creators’. Can the Samaj Sebi Puja be viewed with the same lens we use to judge interactive installation art? How does the notion of authorship change then, in such instances? Is it necessary to bring in the concept of the ‘author’ at all when speaking of these encounters?

Also, given that this astonishing creativity is designed to be ephemeral, does it say something about our attitude to art and aesthetics that cannot be explained by existing notions on these matters? Is it possible to see Durga Puja as a sort of gigantic, annual exhibition, where the boundaries between art and life, ritual and theatre, performance and worship, are blurred, challenged, recreated anew?

One of the things that educationists and philosophers of pedagogy bemoan about our modern education system is how little time and space are given to the arts in school and university curricula. How does the experience of Durga Puja affect the sensibilities, especially of the young? There are always a lot of young people in all the Pujas. Admittedly, they are doing a host of other things — gorging on oily foods, inaugurating romances, celebrating the few curfew-free days they enjoy, and so forth — but surely the experience of such artistry and creativity makes some kind of mark on them?

Some might object that, by itself, Durga Puja does not raise such issues; that these questions are simply the products of our inquisitive, irreligious minds, which ignore the devotion from which all this springs. And, perhaps, they are right. But as an otherwise unremarkable, if teeming, metropolis explodes each year with a celebration that transcends all divides — bringing within its fold a diversity of faiths, classes, sects and beliefs — one cannot but ponder just how Durga Puja shapes those of us who, willingly or otherwise, become participants, on an annual basis, in what one perceptive observer has labelled ‘the biggest carnival on earth’.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years