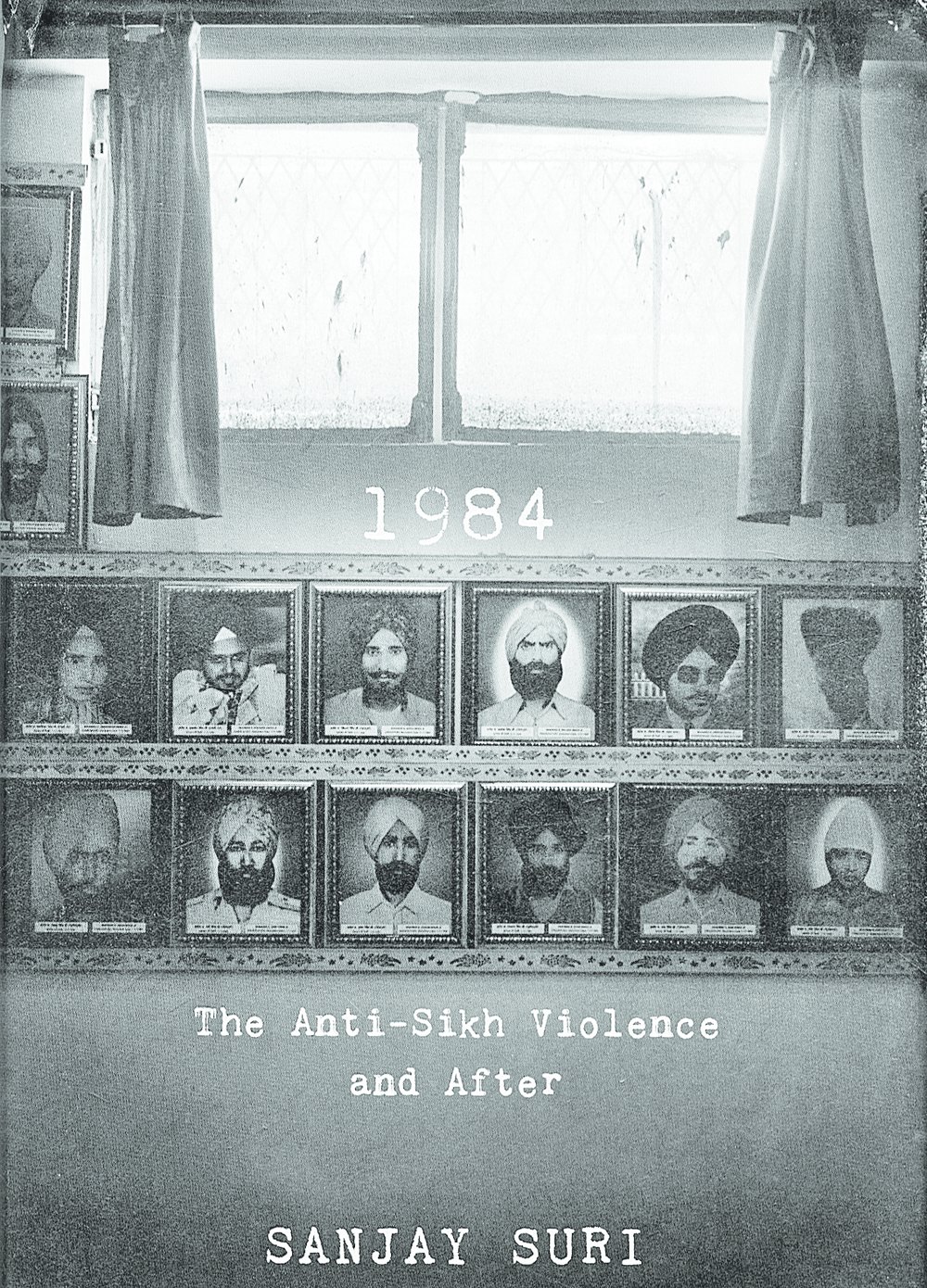

1984: THE ANTI-SIKH VIOLENCE AND AFTER By Sanjay Suri, HarperCollins, Rs 499

"The obvious", Sanjay Suri reminds us in a passage of this book, "does sometime need to be said." 1984, Suri's account of his experiences of reporting on the organized butchering of Sikhs in Delhi after Indira Gandhi's assassination, reiterates the need to state some unpalatable truths, which are evident to all but the people and the institutions with blood on their hands. Much of what Suri analyses - the Punjab problem, Mrs Gandhi's assassination and the subsequent killing of Sikh citizens - is already in the public domain. But what Suri does is join the dots to piece together a chilling narrative that unmasks a conniving, vengeful State.

Rahul Gandhi's denial of the Congress's involvement in the bloodshed may have prompted Suri to present his version of the events. But Suri's account should not be read merely as a chronicle that contests a contrasting narrative. Its importance lies in its ability to expose the systemic capitulation - the result of criminal collusion among the then government, bureaucracy, law and even the media - that precipitated the crisis that was 1984.

Suri's post-mortem, buttressed by revelations of policemen who served on the front line, bares a top-heavy Indian State. Once the government communicated its unwillingness to prevent the carnage, the entire administration, having taken the cue, came to a grinding halt. Suri's investigation unearths compelling evidence of the extent of the collusion. In a controversial speech, Rajiv Gandhi, who had inherited the prime ministership under trying circumstances, had talked of the earth shaking "a little" on account of the fall of a mighty tree. If the former prime minister appeared apathetic, his lieutenants, Suri reveals, showed a perverse urgency to implicate themselves in the violence - albeit indirectly. Suri remembers seeing Kamal Nath orchestrating the movements of a menacing crowd at Rakab Ganj. He also writes about another Congress MP haughtily demanding the release of partymen who had been caught in the possession of goods looted from Sikh families.

Suri widens the ambit of culpability to include legal procedures that are still in place. His encounters with the Ranganath Misra Commission set up by a Congress government reaffirm the collective cynicism regarding pliant judicial bodies and their role in subverting justice.

Significantly, the media, too, were not immune from acts of omission. Suri concedes that too many reporters were missing from the scenes of carnage, thereby enabling a sinister dispensation to conceal the horror that was being perpetrated. Even TheIndian Express, the feisty publication that employed Suri, decided not to report on the rapes so as not to vitiate the atmosphere further. Soli Sorabjee had remarked famously how, in 1975, the media "were asked to bend and they crawled". In 1984, Suri contends, "the media could have spoken at least a little, and it shut up."

An investigation by an intrepid journalist is expected to throw up surprises. Suri does not disappoint on this count. The security lapses that led to Mrs Gandhi's murder expose the ease with which the assailants breached a supposedly fool-proof system. (Satwant Singh's request to change his duties was accepted, and both Beant and Satwant were posted together, even though both had been listed as suspects by intelligence agencies.)

But not every revelation would dishearten readers. Suri records the heroics of a handful of conscientious policemen - Maxwell Pereira is one example - who discharged their duties in the face of nearly insurmountable odds. Suri also demonstrates an interest in the sociology of violence and the myriad consequences of displacement. He shows that the poor, who resided in the least protected areas, bore the brunt of the violence. His conversation with Mohan Singh, who escaped the massacre in Trilokpuri, underlines the challenges that confront rehabilitation policies. Paltry compensation seldom brings about a sense of closure. Suri argues that justice, which continues to elude the victims, could have acted as a balm on the festering wounds.

The legacy of 1984 is not only of a colossal political failure. Suri's analysis shows that 1984 also set a precedent for pogroms of the future. The similarities between what happened in Delhi in 1984 and Gujarat in 2002 would not be lost on the reader.