At the CoP26 in Glasgow, India pledged to net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, with specific commitments at a shorter horizon to obtain half its energy from renewables and lower the carbon intensity of the economy by at least 45 per cent from 2005 levels as well as the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes by 2030. The commitment to a low-carbon future is commendable, more so because of our long-standing demand for climate justice and fears that faster decarbonization could extract a growth sacrifice, holding back advancing the living standards of a large population. The decision is beneficial from global and domestic perspectives for climate change knows no borders while for ourselves, the environmental, health and economic gains due to rapid technological progress increasingly outweigh the mounting costs of climate extremities.

The transition to net-zero will be a structural economic transformation of gigantic proportions in the forthcoming decades. Production, consumption, institutions, markets, macroeconomic variables and policies, which are deeply intertwined with fossil fuels — coal, oil and gas — will reorganize towards cleaner fuels, industrial processes and consumption patterns. Such profound shifts will impact all aspects of economic life. Some sectors, segments and industries will shrink or disappear over time, replaced by new green ones; others will transform or adapt. Because shifts in technologies change relative costs and prices and the returns to investments, macroeconomic variables, such as inflation, exchange rate, fiscal and external accounts, will also be impacted, resetting the related policies in accordance.

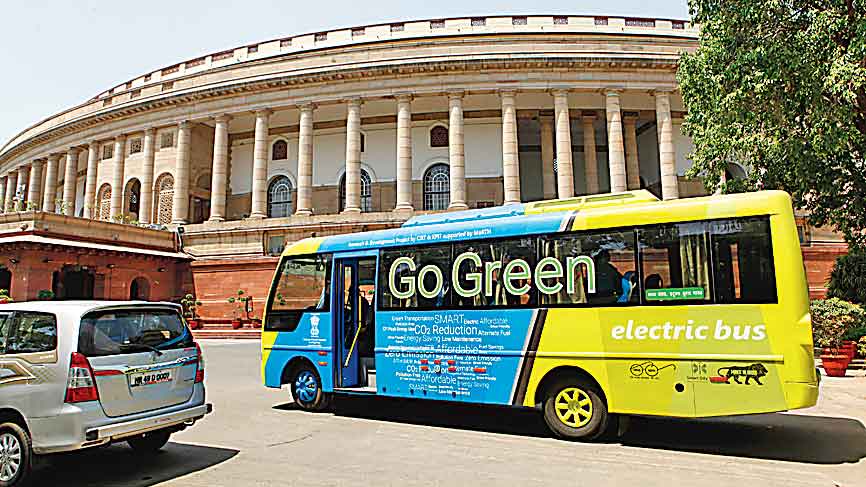

Not all of these evolutions are anticipable with complete precision. Neither is the time horizon certain despite the planned targets as surprise developments can slow down or accelerate any of these. Some significant elements are foreseeable though. The progressive reduction of carbon footprint will mainly come from an energy switchover to reverse the present primary mix from fossil fuels towards renewables such as solar energy. Carbon-intensive industrial processes using iron and steel, cement, chemicals and non-metallic minerals will shift to adopt cleaner technologies, which are presently underdeveloped or yet to become cost-effective. Likewise, petrol-diesel transport vehicles with internal combustion engines will give way to electric vehicles where technology solutions to close the cost gaps are a work in progress.

Like any fundamental change, the green transition, too, brings unique challenges, new opportunities and some risks. The vast coal economy will gradually phase out, resulting in loss of its output base, jobs and resources in the regions of its location. The long road to 2070 seeks to minimize these but, nonetheless, there are challenges for both national and subnational governments whose presence dominates the segment. Inter alia, this is to manage a smooth, equitable changeover through mitigating actions, creation of alternate investments and employments, restoring degraded land, amongst other adaptation needs.

By comparison, the changes in industry and transport are privately led. These are driven by technology availability and access, cost of capital, consumer demand and competitiveness concerns because of which the fluctuations here are uncertain. Overall, several industry supply-chains will reconfigure, new ancillaries emerge, workers will retrain or upgrade skills to new tasks, relocate or retire. Transformation of the large automobile sector will span from primary to component manufacturing as EVs are more capital-intensive, require batteries but few components. These changes will be similar to past and current disruptions, such as those caused by information and communications technology, artificial intelligence and automation, aggregation and e-commerce. Resources, or investments and labour, will reallocate to newer businesses, locations, tasks and jobs that will emerge in the process.

Households and individuals will be exposed to the changes through employment (as workers), consumption (electricity, transport vehicles, petrol, diesel, building material) and asset (land holdings) channels. The challenges here are of electricity pricing, sorting out tangles in power transmission and distribution, and large green-grid investments. Public resources and policies have a major role here given the dominating State presence. If managed carefully, there can be large economic gains for households and business consumers from lower fuel expenditure over time besides health gains from lower pollution hazard. Of course, there will be an adverse impact on government balances from the loss of fossil fuel levies, raising the challenge of alternative tax bases to preserve revenues. At the aggregate level, as prices and costs become more certain and macroeconomic fluctuations settle, lower operating costs will free resources for consumption, investment and imports of greener and other goods and services.

This is only a generalized economy-wide shift in the pathway to 2070 with associated challenges. It is not sans risks and unanticipated developments, especially as the world economy is geared towards faster decarbonization. Many countries have pledged to net-zero targets earlier than 2070 and, for the first time, agreed at CoP26 to draw specific policies to wean away from fossil fuels that cause anthropogenic climate change. Simultaneous, unidirectional efforts to reduce fossil-fuel dependencies will increase the likelihood of alternative, clean solutions for areas where there are gaps currently. There’s a concerted push by governments and the private sector — global financial markets, investors, shareholders and, increasingly, big corporates are favourably positioned towards climate mitigations away from dirty fuels. Technology, costs and price uncertainties are, therefore, high.

These forces and churns also provide new investment opportunities. With a global green transition to which India has committed to contribute, this demand ought to be exploited early. To establish a lead in green technologies and investments, the private and public sectors need to move fast and public policies need to enable that. A first-mover advantage will provide the investment impetus India desperately requires, raise exports, empower faster growth than achieved in the last decade, and create jobs for a fast-growing labour force. It must be remembered that the magnitude, distribution and balance of the new opportunities and challenges will depend on the responses — public and private — to the structural shift towards a net-zero economy.

Renu Kohli is a macroeconomist