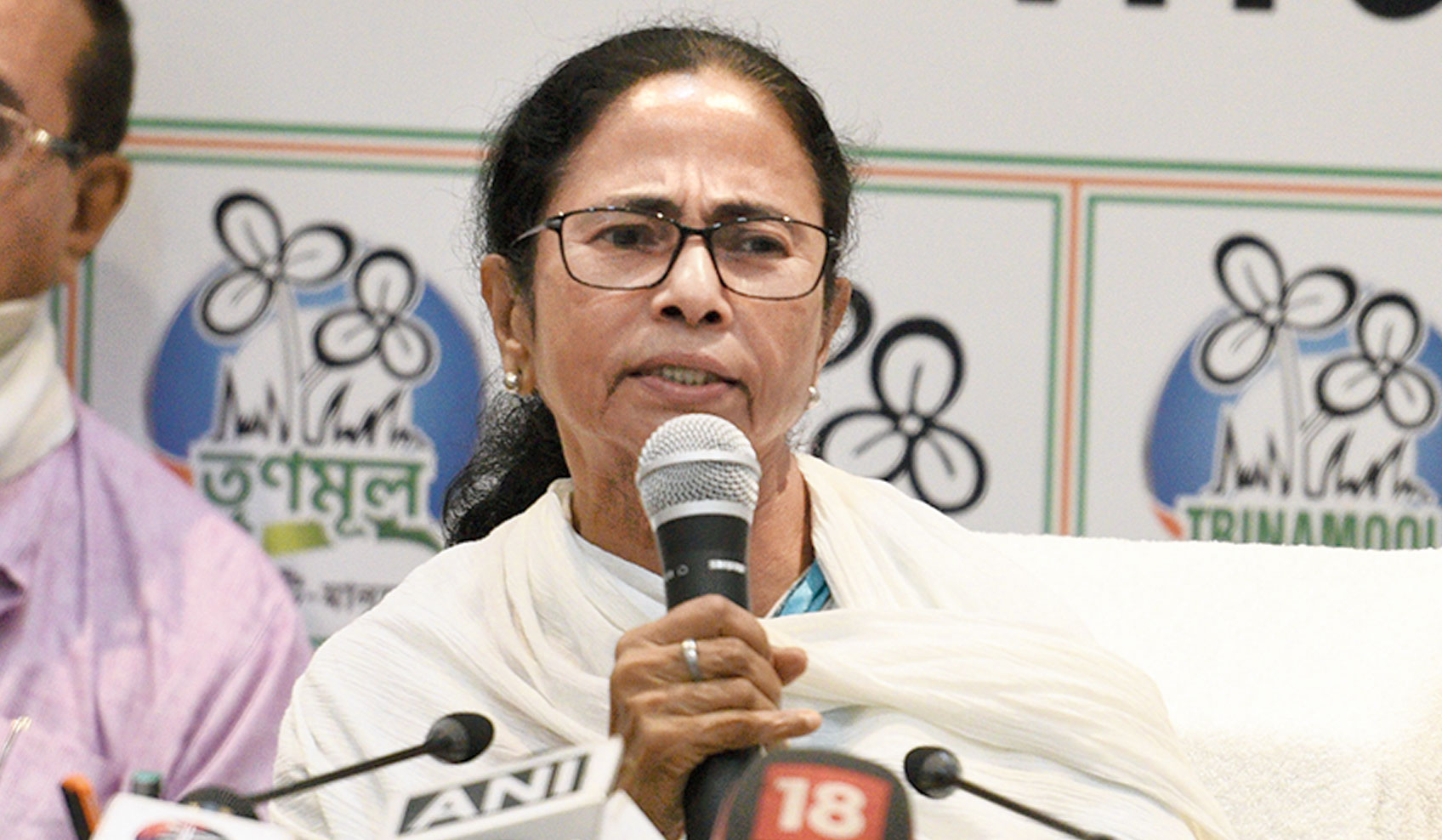

Mamata Banerjee began the 2019 general election in the grand hope that with a clutch of nearly 40 Lok Sabha seats, she would be ideally placed to become the first Bengali prime minister of India — a prize that eluded Jyoti Basu in 1996 and Pranab Mukherjee in 2004. She had made all the preparations to ensure that her claim for the top job would be considered very seriously in the event Narendra Modi failed to win a majority: a solid home base, networking with all the non-BJP leaders, and uncompromising hostility to the Bharatiya Janata Party. However, like other regional leaders with prime ministerial ambitions — Ramakrishna Hegde and N.T. Rama Rao in 1989 and Mayawati in 2009 — she was undone by the voters. First, quite contrary to the make-believe world that was on display at the grand rally at the Brigade Parade Grounds, Calcutta, on January 19 this year, the BJP was returned to power with an absolute majority, improving its high 2014 tally. Second, her ridiculous boast of winning all the 42 seats from West Bengal came to nought when the BJP won 18 seats and the Congress a further two. She won 22 seats from her home state and was so deflated that she responded to the setback with verbal incoherence — ‘losing does not mean defeat’ — and two days of silence when she poured out her woes in verse.

Defeat is not a novel experience for Mamata. In 2004, the Trinamul Congress — then an ally of the BJP — was reduced to just winning Mamata’s own Calcutta South seat. A doughty warrior, she was mercilessly harassed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Parliament and had to be rescued more than once by BJP members. Her defeat in the assembly election of 2006 —when she teamed up with the Congress — was equally devastating. However, since the Lok Sabha election of 2009, Mamata had an uninterrupted run of success in both parliamentary and assembly elections. In 2019, she approached the general election confident that there was no worthwhile Opposition left in Bengal: the Left was in total disarray, the Congress had been reduced to a rump by a series of defections to the TMC, and the BJP lacked any meaningful organizational presence.

The BJP’s spectacular performance in 2019 was a real shocker to Mamata. As she stared at the outcome in utter disbelief, her initial response was one of denial. Visibly angry, she attributed the results to EVM rigging — a silly theory that was repeated to her by nervous sycophants — and demanded the paper ballots that had seen the TMC win nearly one-third of the panchayat elections uncontested the previous year.

However, regardless of her initial disorientation, Mamata has been quick to respond politically.

First, having realized that she took her eye off the ball, she decided it was prudent to focus her entire energies on preparations for the assembly election of 2021. With the BJP having emerged as her principal opponent, she saw no reason to deviate from her total war against the Modi government. She boycotted the swearing-in ceremony on May 30 because the BJP also extended an invitation to the families of party workers killed in the clashes with the TMC over the past year. She followed it up by refusing to attend the Niti Aayog meeting convened by the prime minister on the plea that the erstwhile Planning Commission — conceived first by Subhas Chandra Bose in 1938 — was a better development agency.

Secondly, in line with an understanding that the destruction of Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar’s bust on the eve of the final round of polling — which she blamed on the BJP — had fetched her good electoral returns, Mamata chose to persist with her sub-nationalism. She was quite spirited in debunking ‘Jai Shri Ram’ as un-Bengali and came dangerously close to threatening those who chanted it as a taunt as outsiders who had failed to comprehend their guest status in the state. Simultaneously, in line with the poll data that suggested that she just about survived the BJP groundswell on the strength of the solid support from minorities, Mamata reinforced her commitment to giving Muslims a special political status. It is her understanding that she needs to maximize votes from a community that constitutes some 27 per cent of the electorate as a counterweight to Hindus who have become unreliable.

Thirdly, while recognizing that the vote for the BJP was as much a vote against the TMC’s excesses as much as it was a positive vote for Modi, Mamata threatened her own party with resignation, knowing fully well that her offer would be turned down. She berated errant MLAs and threatened organizational heads with punishment and even seemed to be expressing her displeasure at her own nephew. However, confronted with the reality of a BJP that seemed to be anxious to poach her MLAs and local body representatives, she quickly backed off from taking any action. The nephew resurfaced on the dais at the Eid gathering last week, and the MLAs who had failed to deliver were let off with a warning. Mamata decided that it was too risky to change course at this stage of the innings.

Finally, Mamata has signalled that the only way of checking the BJP is to make life absolutely hell for all those who are associated with the saffron party. Last week, posters went up in different hamlets of the state, particularly around areas where the BJP had established a lead in the Lok Sabha poll, declaring them to be ‘No BJP zones’. In Sandeshkhali, on the Indo-Bangladesh border, this led to a wild TMC leader shooting down at least two BJP workers dead. Three other BJP workers are untraceable which would imply that the Sandeshkhali killings may join the gruesome killing of the Sain brothers in Burdwan by the CPI(M) in 1970 as bloody landmarks in Bengal’s history of violence.

It is unlikely that the Sandeshkhali killings flowed from definite instructions from the top in Calcutta. However, the ‘inch by inch... badla’ message that Mamata had given was probably interpreted by lesser TMC leaders as a signal for unleashing political violence. In Howrah district, in a grisly repeat of events in Purulia, two men were left hanging from trees for actively supporting the BJP and chanting Jai Shri Ram in the recent election. In other parts of rural Bengal, people had their homes destroyed and heads smashed for daring to endorse the BJP.

Mamata is aware that the spiral of political violence will be a provocation to the Union home minister, Amit Shah, and she may be secretly hoping for the BJP to impose president’s rule. But the BJP seems in no mood to confer Mamata with the halo of martyrdom. Instead, the state BJP has chosen the path of victimhood, while underplaying the fact that in many areas its supporters are actively hitting back. It is also likely that the blend of martyrdom and retaliation will also be followed by some firm action by New Delhi against TMC leaders. Yet, the Centre overdoing things can backfire but the presence of a Modi government in New Delhi has a special significance. It is the existence of a strong Centre that has seen a flood of defections from the TMC, Congress and the CPI(M) to the BJP. This is unnerving Mamata and at the same time loosening her grip on the administration. To make matters worse, the TMC leadership is fast losing all residual control it had on its own supporters who have seen the present uncertainty as an opportunity for direct action.

West Bengal, it would seem, is headed for another bout of turbulence as it considers its future options.