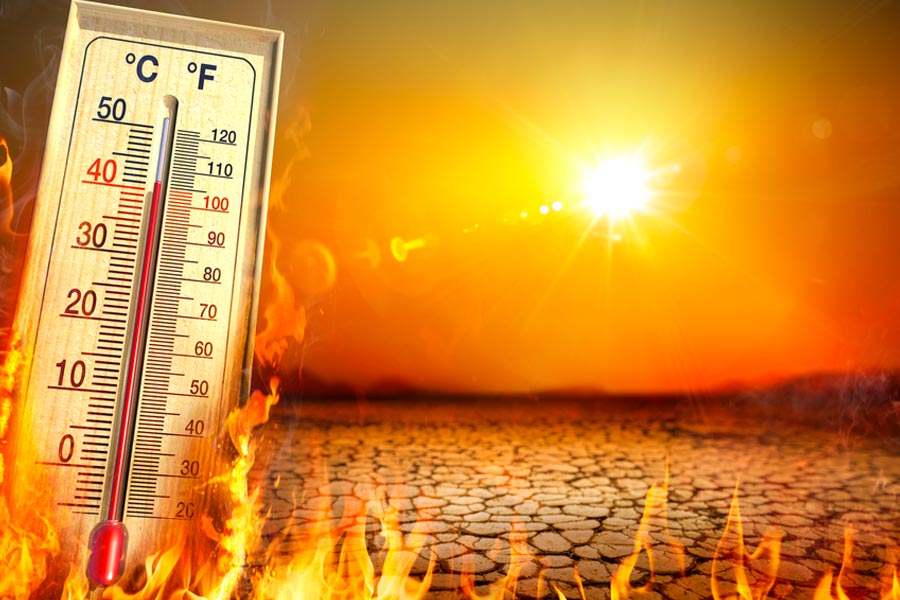

“Be afraid, be very afraid,” says a character in The Fly, a horror film about a man who turns into an enormous insect. It captures the unease and disgust people often feel for the kingdom of insects — cockroaches, mosquitoes and creepy-crawlies of all kinds. However, ecologists are increasingly seeing the insect world as something to be frightened for, not frightened of. With an estimated 5.5 million species, insects are the most diverse group of animals on the planet, accounting for 80% of animal life on earth. But both the number and diversity of insects are declining around the globe owing to habitat loss, pollution and climate change. A paper published a week before the ongoing CoP27 commenced warns that if no action is taken to better understand and reduce the impact of climate change on insects, it will drastically limit the chances of a sustainable future with healthy ecosystems. The paper also found that fruit flies, butterflies, and flour beetles can survive heat waves, but males or females become sterilised and are unable to reproduce, thereby becoming zombies — the “living dead”.

The signs of this extinction are coming closer to home. The presence of the once-ubiquitous shyamapoka — the green leafhopper — has diminished in their former fiefs of Jhargram, West Midnapore and Bankura, say news reports, even though ‘autumn’, or what is left of it, has come and gone. This is consistent with the prediction by entomologists that say that 40% of the global insect population is threatened with oblivion. The reasons for their disappearance include, among other factors, excessive pesticide use by farmers, rising global temperatures, habitat fragmentation and destruction and so on. The consequences of their annihilation would be drastic. Insects enable plants to reproduce, through pollination, and form the base of the food pyramid. One of the fundamental mechanisms that made life on earth possible — insect-borne pollination among flowers and food crops — is now gravely imperilled by this unfolding entomological disaster.

Yet, the serious depletions in the insect population arguably remain on the margins of the public discourse on climate change. There are several explanations for this skewedness. Evidence suggests that species higher up the food chain occupy a disproportionate share of the attention of scientists, conservators as well as policymakers. The question of being attendant to the scales — minor and major — of the environmental crisis assumes critical importance in this regard. Moreover, scientific journals, it is believed, remain indifferent to contributions from the constituency of amateur researchers who are recording the changes on the ground. While delegates at the CoP-27 wrestle with the big picture — funding, emission cuts, sustainable development goals — they must not lose sight of the minutiae. Making urban and rural ecologies receptive to the regeneration of insect populations through scientific interventions — such as cutting down the use of pesticides — must be on the agenda. Another potent, but less discussed, means of saving insects is public memory: the remembrance of a time when the passing of seasons would be heralded by the arrival or departure of insects could spur collective remedial action.