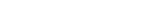

A well-known publisher, a poet who got ‘discovered’ online and a photographer who picked up the camera to express the unrest within — Naveen Kishore wears many hats.

My Kolkata caught up with the author of Mother Muse Quintet about his books, his ongoing photography exhibition and more. Excerpts:

From Knotted Grief to Mother Muse Quintet —- how would you define your journey as an author.

Writing is an independent exercise from publishing. I have been writing for the past 12 years — every day. So, it is a practice, like we do riyaz for music. You always wish that you get published but it’s not a priority, it is definitely not going to happen from your own publishing house because then it is too easy. The act of publishing happened accidentally. My joy comes from writing and sharing. In the circle of authors, publishers and translators, somebody recommends and you end up being published online somewhere. One of these online things reached an Australian publishing’s poetry editor by chance, who reached out to me and asked ‘do you write?’, I said I do. ‘Do you have a manuscript?’, I said no, I have a folder. The editor said, ‘Send it to me’. The man created a manuscript and I responded to it, with very little intervention from my side. Another friend in America, who used to run the bb, gave it its name. I was calling it Kashmiriyat, but she named it Knotted Grief. So, the journey started a long time ago. I was a child when we were in Kashmir and the memories were of a place unspoilt, yet to be taken over by the Indian film industry, yet to be discovered by tourists, yet to become a stigma. Mother Muse Quintet is what it is. It is about Prem, my mother, who used to let me call her by first name.

Tell us about the thought process behind authoring and naming Mother Muse Quintet.

It was written years after her death… I still write about her. But the trigger was not some self-conscious attempt at understanding grief because there was a lot to grieve about. In this case, it was the specific moment of writing and sharing instantly with my sister who was always away, first in boarding, then was married. I was just sharing memories with her. I was writing every day and sometimes more than one or two things. So that’s how the impulse started. At some point, I also realised I can also remember things from when I was four, I could remember things from when I was her walking companion during my school days. We used to live on Ripon Street. We used to walk to Trincas, where my father used to work. We used to stop there for ice cream and some mushroom on toast for my mother, and used to adore Eve, who sang there. We (Prem and Naveen) used to talk and she was a great storyteller and that’s in the book. Therefore, when I was involved in her caregiving, my struggle was one of finding a language because hers was disappearing. And then came a point when I had to seek her permission to amputate her leg. And I did not have the words, not because I was at loss for words. I didn’t know if she was getting it but just nodding in trust.

If I say Knotted Grief, what are the three words that come to your mind?

Good lord (laughs)! Obviously knotted and grief, and knotted also implies the unravelling of grief. Unpredictability is another word that comes to my mind.

And if I say Mother Muse Quintet…

Clearly my mother, her companionship and also a sort of gift that she gave me — permission to call her by her name. The muse is not waiting in solitude for the lightning to strike. No. It is the lifetime of values that are conveyed through watching other people. You don’t teach children, you just be yourselves. It also happens in relationships.

Your recent book-reading session in the city had an amalgamation of poetry and sound. Why did you team up with Jivraj Singh and what was the thought behind selecting sounds like chirping of birds, water and so on with the poetry? Why did you choose a theatrical atmosphere for the reading?

Jivraj is a wonderful musician. He created something that was different each day. For example, the night before the book reading, he (Jivraj) played Kundan Lal Sehgal’s Ek bangla baney nyara kind of song because he remembered from a memory of mine that he had recorded — where I spoke about Kashmir and how my dad used to sing in a Sehgal-voice. So, I am reading and this song suddenly plays — it was a jugalbandi of sorts.

Tell us about your upcoming books.

The next one that I want to write is called Naked, Like Breath. It is more about a man and woman — and loss of a certain kind of relationship. It’s also about tenderness.

From being a publisher to an author — how has the journey been?

Seamless. Writing is as much a daily practice as publishing. The actual act of publishing a book is like any other first-time author. You do it strictly on merit. I haven’t published with Seagull! It does not make sense to publish your own books. Unless you are T.S. Eliot! So, I waited to be discovered and that happened organically.

Do you think your roles as an author and publisher influenced each other ever? How do you see the future of books and literature?

Not sure if there’s been a conscious influence. I have been writing every day actively for the last 10 years. It is something I do. One responds to the times and life and evolving cultural practices. I don’t see the future. Period. I sometimes ruminate on what is past. It helps one understand. The practice of making books is both focussed and slow, and in many ways an intimate one. It is close to one as are the authors and translators. The books will stay. Reading will not stop, perhaps the surfaces will change — tablets, kindles, phones... But writers will continue to write and there will be readers.

You are also an artist and a photographer. Why did you name your most recent exhibition ‘In a Cannibal Time’?

I didn’t. It existed in the form of a Seagull Theatre Quarterly, published in 2002. The issue was devoted to how theatre and art resist and document the ‘dark times’. The issue was titled Cannibal Time, which is a line from a poem we came across at the time. An apt description of the present time I think — not merely dark but cannibalistic even!

Tell us about your penchant for photography. How do you see photography as a medium of expression?

This needs another book, my friend! Or at least a long essay — things that I imbibed from theatre, dramatic performances, cinema, art and so on to form my constantly evolving aesthetic. Photography merely expresses this learning, in the form of still images, which tell select stories from life and times of people around me.

The exhibition has performing arts as a medium of expression and a common thread with three different stories. If you were to describe the exhibition — the statement, the purpose and the message that it carries — how would you describe it?

I tried to observe, keep a distance and create something without being in the ‘thick of it’, to document, to be moved in a manner that invites anger. Shame. Horror. Paralysis. To capture ‘despair’ through films. I tried to select frame after frame of anguish, then print it on paper, install it in an art space, invite others to see, to feel and to remember. The ‘when’ is not always important nor are ‘labels’ that mark a particular moment of atrocity inflicted by nations, states, by states within states, by people like you and me. Genocides, riots, wars… This body of work is an attempt to create awareness of such moments in time, both as a witness and a helpless bystander. The trappings of theatre are always present in my work. Shadows in smoke, projections, harsh beams of light, dust and ashes — all combine to suggest the apocalyptic. I look for the ghosts, dig them up and put them together in a room and take their portraits — as a population, as victims, as perpetrators, as all of us.

When were the photographs taken? Will there be any other upcoming exhibition?

Over the last 20 to 23 years. No idea if more will happen at this moment.

Be it your collaboration with musician Jivraj Singh during the book reading of Mother Muse Quintet at Waypoint, Kolkata, or with author Ranjit Hoskote during the upcoming art exhibition, how do you see the amalgamation of two genres of performing arts or literature coming together?

I have no labels. I don’t know if I am amalgamating. It is all very intuitive. Jivraj, my musician friend, and I, responded together to the music in the poems and created a soundscape. With Ranjit (Hoskote) the conversation is around my images because he has curated the ‘Epic’ and the ‘Elusive’ series for the show. It is simply what appears in a conversation — intuitive and evolving. There’s no pre-prep except our own natures and our own practices as a photographer, designer, poet, publisher and his, as a poet, translator, curator and cultural theorist.