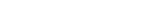

There is an unabashed flamboyance to Niladri R. Chatterjee’s demeanour. Not in his fashion sense, but in his use of language. Despite coming from academia, the author refuses to play by the rules. Chatterjee was at the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2024 to promote his book, Entering The Maze: Queer Fiction of Krishnagopal Mallick, when My Kolkata caught up with him. What followed was a fascinating chat on writing, lust, polyamory and more.

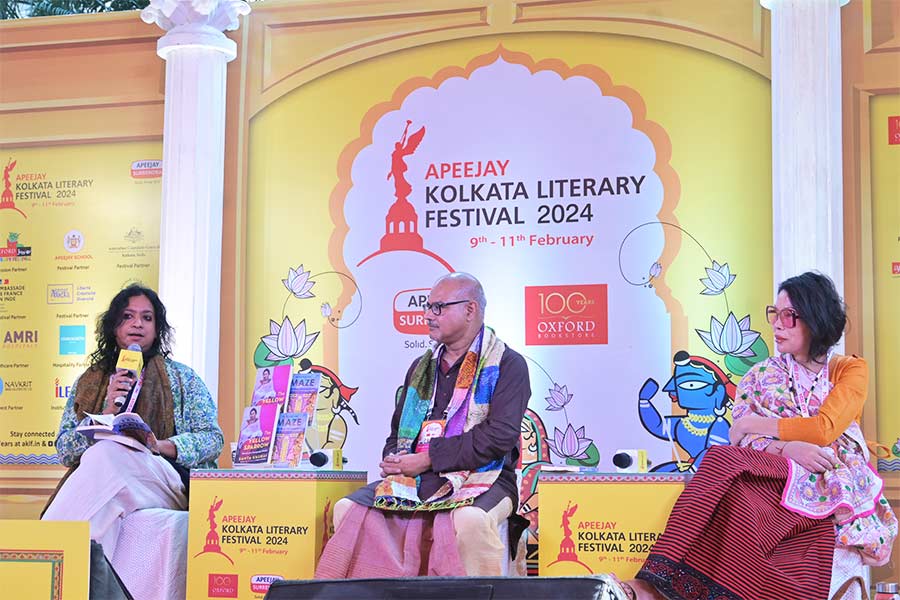

Released last year, Entering the Maze is an amalgamation of Krishnagopal Mallick’s writing, published in Bengali little magazines. What makes it special is Mallick’s unfiltered accounts of exploring desire and pleasure. The book not only moves away from heteronormative relationships, but also highlights the beauty of lust, without shame. Naturally, translating the text proved to be a transformative experience for Chatterjee. “As queer people, we are bombarded with narratives of pain and suffering. I always wondered, ‘Is that all there is?’ And then came Krishnagopal Mallick with his radiant world, where he has a wife and child, but is constantly picking up men and falling for them. I just had to translate it,” he said with a smile.

Queer narratives and happy endings

Mallick’s writings reminded Chatterjee of E. M. Forster, who envisaged a happy ending for a gay couple in 1913, while writing Maurice. Foster’s queer friends criticised the novel, because they felt that the happy ending was mythical. However, he remained adamant, wanting to keep a happy ending, primarily because life didn’t give one. The fact that Forster didn’t live to see his novel published while Mallick did, surprises Chatterjee even more. “I scoured world literature but couldn’t find any writer who was married and had a child, but still wrote openly about his sexuality. Mallick’s text has absolutely no guilt or hand-wringing about the consequences, and he even writes about falling in love with another boy as a teenager. The novel ends happily with the boys finally making out!”

For Chatterjee, this isn’t the only happy ending in the book, pun intended. He is filled with wonder at how candid Mallick is while talking about having sex as a 14-year-old boy, with men much older than him. “At no point does the boy say, ‘Oh my god, this man has scarred me for life. He simply pulls up his pants and says, Okay bye!’,” chuckled Chatterjee, while reminding readers that the age of consent was 12 during Mallick’s youth.

The simplicity behind Krishnagopal Mallick’s writing, and his unapologetic treatment of lust were transformative takeaways for Chatterjee

‘People have started to sentimentalise sex’

Chatterjee also highlights how in Mallick’s writing, sex and love exist independently. In a world where ‘good’ queer narratives are often interlinked with the idea of a family-like relationship, Mallick enjoys fulfilling more carnal desires. “The whole country is getting more conservative, and gay men are no exception. People have started to sentimentalise sex. The narrative for good queers is to get married to a nice partner, and settle down with three children and a dog. On the other hand, Krishnagopal talks about cruising around College Square in the 1990s, and being eyed by men during his morning walk. Even in his fifties, he is well aware of his sexual charisma, and has no qualms about putting it into print!”

Chatterjee acknowledges that there is pushback when pleasure isn’t linked with love. “I don’t like the slogan, ‘love is love’ because it completely obfuscates the real problem. If people want to get married, that is great, but it shouldn’t become the ideal. The entire queer struggle isn’t about how people weren’t allowed to be in love, it was about how they weren’t allowed to have sex.” While he is glad that shows like Made in Heaven are changing this ideal, there is a long way to go.

While shows like ‘Made in Heaven’ are changing the discourse on queer love and relationships, there is a long way to go, says Chatterjee

Why Mallick’s writing feels contemporary

Mallick’s writing feels even more contemporary to Chatterjee, who identifies as polyamorous. He opposes the societal norms of loving and engaging only with one person, arguing that it is inhumane to have such a demanding expectation from someone. Chatterjee’s views on the topic have led to several uproarious seminars, leaving audiences scandalised. “I only ask people to look within, and answer honestly. ‘Have you always been in love with one person? Is the person you are emotionally invested in, also the one you are having the best sex with?’ It is terrible to think that your emotional and sexual needs will be fulfilled by one person. I would die if someone wanted this from me. Let’s look at relationships with less rose-tinted Karan Johar-esq glasses please. Maybe that will lead to less casualties in my seminars,” he chuckled.

Drawing a parallel with friendships and family, Chatterjee added that no one can fulfil all your needs. However, evolution of the mind doesn’t go parallelly with society, and being an openly polyamorous person often attracts judgement. “People exclaim, ‘I thought you were only mine’ and equate it with cheating. What they don’t acknowledge is that monogamy is linked to seeing someone as your personal property. I have a fridge, a car, and a boyfriend. But you don’t do this with a human being,” he said with a sigh.

All in a day’s work

Chatterjee’s other attraction to Mallick’s text — apart from the unapologetic stance — is its simplicity. He confesses that translating the text was easy, as his objective was to preserve the lucidity of Mallick’s Bengali, but in English.

While Entering The Maze has received an award, Chatterjee has no time to rest. He has already begun work on a fictional text, which will be centred around polyamory. He is also working on translating a hugely popular writer, although he can’t reveal more at the moment. And between all this, he continues to teach at the University of Kalyani. How does he manage to pack so much into his schedule? “I don’t believe in wasting time. That’s why, people in my seminars either know what to expect, or are carried out in stretchers. Either way, I enjoy having fatalities in my seminars,” he signed off, with a laugh.