Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Post Colony by Rochona Majumdar is a researched and erudite study of the three stalwarts whose films put India on the global stage –– Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen. It was a keen interest to delve deep into the film society culture prevalent in the country and the trajectory of arthouse cinema in a post-colonial world that led Majumdar, an academic, to trace a comprehensive account that would prove seminal for researchers ahead. We spoke to the author to understand her thoughts behind the book. Excerpts.

Tell us about the inception of this book.

There are three central figures at the heart of this book –– Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, and Mrinal Sen. When I was growing up in Calcutta, everybody knew them and their work. When I joined college, there was a film society –– the Presidency College Chalachitra Sansad. I frequented their screenings. This was the early ’90s. My friends and I were not snobby about watching only particular arthouse films. We watched everything. One day we’d be watching Debi screened by the society and then troop to watch Kaho Na Pyaar Hai the very next day. As cinephiles, we consumed everything.

I began my academic career as a historian of gender. When I finished Marriage and Modernity and was wondering what to do next, I thought of writing about films because I spent so much time watching them. That’s when I started to read the scholarly literature on Indian cinema, and I was really struck by the fact that there was actually very little on Indian art cinema.

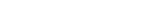

Ritwik Ghatak

As I read more, I realised that this was actually a time when there was very good work being done on Indian popular cinema. And people who were writing about popular cinema then –– Ashish Rajadhyaksha,

M. Madhav Prasad, Rachel Dwyer –– were revolting against a sense of highbrowism and snobbery, saying that there is a lot to be understood from studying popular cinema, particularly about Indian politics and democracy.

This kind of revolt of the popular swept art cinema under the rug. Now there is a kind of reverse snobbery. To think there is little written about Mrinal Sen in English, for example, feels like an egregious gap. I wanted to situate art cinema and those associated with it historically. I wanted to understand them not as each other’s competitors but really as creating a milieu which wasn’t just limited to Ray, Sen and Ghatak, but also included the likes of Rajen Tarafdar, Chidananda Dasgupta and Tapan Sinha –– people that we don’t talk about enough. That’s what took me to it.

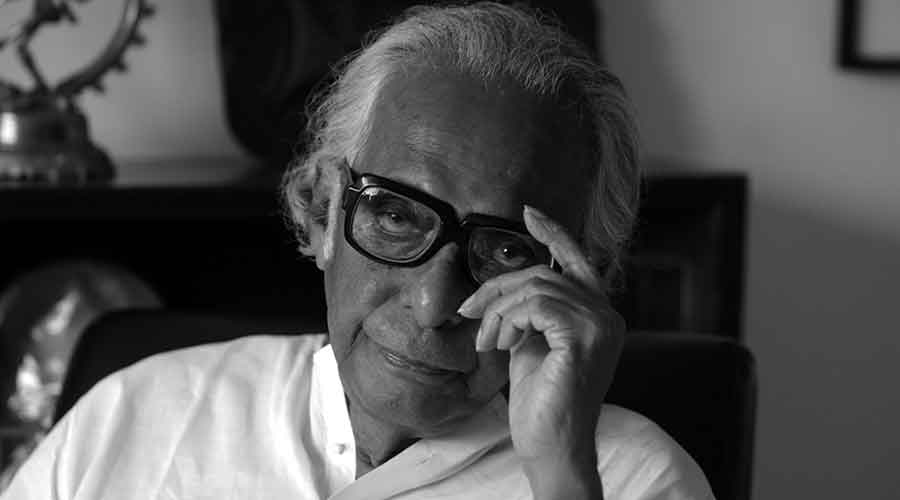

Satyajit Ray

I think in India and certain parts of Europe, there was love for art cinema the, beginnings of which were always tied to a kind of civil social organising –– the cine clubs. These clubs played a very important role in cultivating a particular kind of film sensibility. The history of cine clubs brought me to this project.

Being an academician, you had access to a lot of documented research. What was your research like beyond that point?

Every academic who I read and like, has always struggled to reach a broad audience without diluting what they have to say. The challenge is actually to balance the two and not everyone is successful. I can’t say that I am, but it’s something that I value very deeply. Having said that, one of the challenges of working on Indian cinema is that for a very long time, unlike the other arts, cinema was not taken that seriously. As a result of which the archiving process is even patchier. The National Film Archives in Pune right now is doing magnificent work. My work is indebted to the archives and to the passion of individual film society members. They have preserved publications, many of which are ephemeral. When I began this research in 2011, I actually did a lot of travelling all over the country meeting a lot of people who included Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Girish Kasaravalli, late Satish Bahadur and P.K. Nair (long-time archivist of NFAI). Through them I met other film aficionados who had been film club members, who shared many photographs, journals with me.

You have been very forthright about NFDC’s role in the decline of art cinema in India. Could you please elaborate a little on that?

There was a Film Finance Corporation that preceded National Film Development Corporation (NFDC). They used to give loans to film-makers who would otherwise have a tough time finding producers. Unlike Europe, these weren’t subsidies offered to film-makers, but loans that had to be repaid. So when people say state-sponsored cinema, it’s actually a misnomer. The NFDC eventually emerged as an umbrella organisation and I write about Attenborough’s Gandhi as marking its big moment of emergence of big-budget international films, of which Gandhi was a part. Soon after that, you also have a change in political dispensation and, therefore, cinema became a different kind of battleground where the kinds of films that I’m writing about wouldn’t even be considered for any kind of loan/funding. So, in a sense, that moment of the founding of the NFDC is the beginning of a very long process –– the beginning of the end of a process.

Do you feel that the OTT platforms came in with their big-budget funding and sort of democratised the playing field by hosting content that would otherwise get lost at sea?

I think more work needs to happen on what kind of impact online streaming platforms have. Because of the instant or easy availability of a lot of content, people become cinephiles more easily than it was possible earlier. But, at the same time, the collective experience of congregating and watching films together at the theatre is extremely important. I think we might even have a renaissance of the film society movement. The ubiquity of content does not diminish the urge to get together to talk about that content. There may be a group of people who decide to watch Korean films or Chinese films — they are no longer limited by national or international geography. You can come together on Zoom or Google Meet to talk about films you have watched. Thanks to OTTs, we have access to some really great content which we would never even hear of otherwise. Movies that you would otherwise get to watch only if you happened to be in India attending film festivals. But the waning of the collective experience and engaging in conversation post-screening is something that definitely bothers me.

The other thing is the establishment of the film festival circuits and a certain kind of aesthetics that are associated with small-budget films, specifically being made for that circuit. There is a kind of homogenisation of films that would otherwise be considered alternative. Having said that, I do feel there is a lot of interesting work happening. I absolutely love the portmanteau setup, which is four separate films in one. I thought Made in Heaven was a fantastic show in the way it handled issues of class and sexuality. There are film-makers like Ivan Ayr, whose work I like a lot. Overall, I’d say while I feel very hopeful with the quality of work, I am apprehensive about our ability to form communities of spectators safely post-Covid.