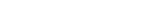

Within their rhetoric of silence, women have shifted between being unobtrusive daughters, self-effacing mothers and wives. Understanding the need to initiate dialogues on women’s lives and bring to light the reality of their being was a daunting task — more so when Jyotirmoyee Devi, one of the earlier women writers of modern Bengal, chose to document the experiences of women in early 20th-century Rajasthan. Thornbird (an imprint of Niyogi Books) published Behind Latticed Marble: Inner Worlds of Women — a collection of some of Jyotirmoyee Devi’s stories, translated into English from Bengali by Apala G. Egan in January 2023. Saturated with the grief of separation from treasured possessions, these poignant stories situate women in their immediate social context and matrilineal legacies.

Through these stories, the author gives the impression that she is trying to initiate her readers into the cultural life of the old Rajputana. The Rajput cultural ethos pedestalised chivalrous and proud warriors, and in that world, women were the catalysts to provide impetus to the heroic tales of men. But Jyotirmoyee Devi's stories deviate from the familiar trajectory, and journey the readers into the concubinage system prevalent among the Rajput maharajas — “Beauties from the entire kingdom were culled and brought to the palace, indeed many a family sold or gave their daughters to swell the harem ranks.” Can life in a gilded cage be pleasurable? This book makes us privy to secrets that did not trickle out of the royal palaces.

Latticed windows add to the artistry of the architecture of Rajasthan, but a lot used to go on behind these that Jyotirmoyee Devi witnessed during her time in this state. Announcing the release of Behind Latticed Marble, the translator commented, “These stories take us into the innermost chambers of palaces; indeed, I have visited many such sites in Rajasthan. My interest was piqued by the fact that these are based on real-life observations. Power play has occurred in kingdoms and occurs in other spheres of life to this day, and the challenges that women face are timeless. An interesting facet to some of these fictional narratives is that they show women pursuing solutions while enlisting support — including that of men.”

Can life in a gilded cage be pleasurable? ‘Behind Latticed Marble’ makes us privy to secrets that did not trickle out of the royal palaces

ShutterstockThe purdah system that shielded women from the male gaze and made their existence almost inconspicuous is explored in considerable detail in these stories. “To the ladies of the harem, family life and the world outside were foreign.” The “harem firmament” is shown as a world in its own right — grace, love, possession, jealousy, betrayal and intrigues are some of the qualities that permeated women’s lives in this space. Royal harems have existed in different parts of the globe throughout history, and polygamy was normalised as just another sacrosanct tradition. In these stories, men are wielders of power and women are marketable commodities. Some young girls were too innocent of the guile of the royal life. Some were enamoured by the luxurious lifestyles of the royals. But once in the harem, women were incarcerated in “an icy cell of loneliness”. Nostalgic recollection of the past was the only recourse to deal with life in the harems for many. The story Frame-Up briefly contextualises this bit of women’s history. “Radha had faced heartache, and Tara, Kunti and Ahalya had experienced their shares of sorrow,” mused the dowager who was framed for regicide.

Jyotirmoyee Devi’s grandfather’s appointment as a dewan, or prime minister, to the Maharaja of Jaipur, helped her observe the lives of the queens and concubines in the royal harem

@rajasen4317/YouTubeThe “glittering powerlessness” of women enforces homogeneity in the ten stories in this collection. Women in misery mostly end in pitiable deaths here. The “whiff of intrigue”, “scent of scandal” and “machinations of women” permeate the tales. But can readers blame these women who “vied with each other for a second royal glance”? These women were products of the social matrix, acutely aware of the unequal gender-power relations, but divested of the agency to ruffle the same. All they could do was replicate the time-honoured traditions in silence and find a sense of totality in the self-perpetuating customs. The author has captured the nuances of palace hierarchy with utmost fidelity — principal consort, wedded queens, and then, numerous concubines. The story Ungendered highlights it — “They had sung and danced their way to the maharaja’s heart and had been granted the title Pashowan, while the lesser favourites but the king’s darlings nonetheless were titled Pardayet.”

In these stories, women are round characters who feel and voice their emotions. Disenfranchised losses — of a part of one’s personality or a hundred-year-old heirloom — governed many of these women’s lives. These stories are not meant to be consumed like fascinating tales of royal palaces, kings and queens of the distant past; these are about women being devoured by overbearing loneliness. The profundity of these stories lies in how they capture the complexities faced by different marginalised sections, and not just women. Half-bloods were the products of the union between the kings and concubines. The royal line of descendants forsook them, and the British Government in India did not recognise them as the rightful heir to the throne. The pain of alienation was also felt by the chief eunuch who gave the readers access to a world where all men were denied. Though the chief eunuch enjoyed considerable power in the royal palaces, the author familiarises the readers with their woe at being robbed of their sexuality and the ability to live a life of freedom, hope and longing.

The society Jyotirmoyee Devi talks about had no tolerance for women who overstepped the social and behavioural boundaries. Life under the Purdah system was no better than living in the Panopticon. Every movement of women in the palaces was monitored by the eunuch and palace guards, and outside, the men in the society presided as the self-proclaimed moral police. The story Courtesan’s Tale is about a confrontational woman. What to do with a woman who chose to fly in the face of conventions? “I simply don’t know what to do with her. She has astonishing courage for a mere girl. She walked all by herself during the night and is far too independent. Please do take her back and if need be, beat her into submission,” suggested her mother to her in-laws.

If read between the lines, the repeated use of the word “labyrinth” is bound to bring to some readers’ minds associations with the Greek craftsman Daedalus’ labyrinth. Only that, in this society, it was not the monster Minotaur, but women of different classes who were trapped, all the while struggling with impuissance. This publication by Niyogi Books is a reminder to celebrate Jyotirmoyee Devi for the sociological depth in her stories, written in the wake of the twentieth century, and for documenting gender in the Rajput communities in Rajasthan with her acerbic wit.