While English language American and British films and shows remain the centrepiece for global entertainment, South Korea has managed, over two decades, to build a steady, loyal fanbase. In the mid 2000s, one would often hear of K-Drama or K-Pop, or the occasional K-Horror — and Oldboy if you’re a movie buff — but the mass reach of these were limited. In the 2010s, things started to pick up with the gradual global domination of BTS. They have become a mass sensation. And deservedly so. Cut to 2019. Parasite is out! The rest is history.

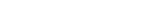

Squid Game is the first Korean show in a post-Parasite world to engage the audience in the same fashion as the Oscar-winning Bong Joon-ho film. In a matter of a month, it was crowned the biggest series by Netflix ever!

The plot of Squid Game is uncomplicated, yet not without its complexities. A group of 456 contestants play a series of children’s games to win a cash prize. But that’s hardly what the series is about.

Meet Seong Gi-hun

Early on in the first episode, we’re introduced to Seong Gi-hun (played brilliantly by Lee Jung-jae), a chauffeur living with his ailing mother. He has gotten divorced and barely gets to meet his daughter who now lives a comfortable life with her stepfather, while Gi-hun lives in a small dingy apartment with no sunlight. He’s drowning in debt, often betting the little he has on horse racing with the hopes of earning a fortune but struggling to pay for his mother’s treatment and fighting all odds to desperately get enough time with his own daughter. In a world where money buys everything he’s a lost man.

As an audience, we empathise with him. We all have the same desires — to be loved and respected by our own while having enough to provide for ourselves and people we love. So it comes as no surprise that when Gi-hun gets a bizarre offer to play a series of six children games with the lure of a huge sum of money, he accepts it. It’s hard to not accept it. We would have all at least given it a good thought

Gi-hun (player number 456), along with 455 others also deep in debt, are taken to an island in the middle of nowhere. In an institutionalised fashion, they’re given a uniform – green tracksuit (the most common colour of school tracksuits in Korea) with a unique number with which they’re referred to throughout the series. They’re controlled by the guards, the mysterious people behind masks, who micromanage the entire series of games. Similar to the players, the guards have their own set of uniforms – pink tracksuits to complement the greens. Little is known about them but one assumes their lives were not very different from that of the players. The games are simple, easy to understand and Korean favourites but, of course, with a twist. Here a misstep (quite literally sometimes) can cost you your life.

Which character am I?

Throughout the series of six games, we’re familiarised with the supporting characters — Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo), Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon), Il-nam (O Yeong-su), Abdul Ali (Anupam Tripathi), Deok-su (Heo Sung-tae), Hwang Jun-ho (Wi Ha-joon) and Han Mi-nyeo (Kim Joo-ryoung). While the uniform tries to fit them in the same box, they come from different socio-economic backgrounds. While one is an investment banker trying not to fall from grace in the eyes of his proud mother, another is a young North Korean defector trying to build a life for her brother; one illegal immigrant wants to make sure his wife and child can safely leave the country, while the other has no family to go back to and patiently waits for his death. They all have desperate reasons to be in this deadly game.

And even in a bizarrely violent survival game setup, the heart of Squid Game revolves around the simple relationships of different families. It truly makes the characters more relatable and you begin to wonder – which character am I in this ensemble

Each actor is so convincing that when one watches the promotional interviews by the cast, they feel unrecognisable. Special mention for Anupam Tripathi, the South-Korean-based-Indian actor playing Ali, whose smile was enough to brighten up the most anxious scenes, and the model-turned-actor Jung Ho-yeon whose masterfully restrained acting will break your heart the more you spend time with her. It’s amazing to see how a bunch of fresh talent can really shine when given the right script.

A children’s play area

The visually tangible world of Squid Game — much of it created by production designer Chae Kyoung-sun — is colourful. The uniforms are binary. The dreamy, interconnected stairways are pink, the walls green. It does resemble a children’s play area. Much of that is contrasted with the dark internal world of the characters — people faced with situations where they figure out the morally correct way to act, making all of them grey, and often quite unpredictable. Even the archetypal bad guy, Deok-su, isn’t a binary tool to add conflict to the story. You hate him but to a degree, you understand him as well. On the opposite spectrum, Sang-woo, the friend who starts out as the most empathetic and intelligent person in the group, is slowly transformed into someone so desperate to win the prize money that he’s ready to go to any extent to stay alive.

As the story progresses the character arcs start taking unexpected turns. The colours of the world start to blend in. This is also reflected in the production design of the final few episodes when the blood starts seeping into the pinks and greens. The interconnected pink stairways aren’t cleaned anymore and the uniforms remain stained with the blood of other contestants. This mix of colours creates different colours, a different visual palette. In the final two episodes, the contestants even ditch their colourful binary uniforms for cocktail suits to have dinner in a monochromatic room which looks nothing like the peepy colourful play areas seen before.

A global tale rooted in Korea

Squid Game evolves into a larger social commentary about hyper-capitalism with the introduction of the VIPs. Much like a Parasite, the economic inequality in Korea becomes a central theme of the series. A group of foreign English-speaking moneybags who fund the Game every year, arrive wearing masks to watch the final two games in person, having already watched the previous four on television screens, much like us, the Netflix viewers. To these VIPs, the Game played with indebted, unfortunate Koreans, is entertainment – lives lost or not, is frankly irrelevant. The gorier, the better. They get to do their ooooh and aaah, and move on. Unlike the contestants, they wear the majestic blacks and golds, and there’s a clear distinction in class from that point onwards. While one group risks their lives in their desperate bid to win the jackpot, the other sits back wearing expensive robes enjoying and joking about why they bet on one player over the other. The evolution of the theme never seems forced. This is the reality of most capitalistic societies. We often don’t consciously think about it but when shown with metaphors in a television show, it truly hits home.

The man of the moment, Hwang Dong-hyuk, already an established director in South Korea, struggled to get this project made for 10 years. I truly believe, however, that this was the time for the series. It doesn’t matter which country you’re from, you can draw thematic parallels raised by Squid Game. While keeping the games and social issues very rooted in Korea, Dong-hyuk has ultimately created a globally relevant show that’s here to stay.

Priyankar Patra is a producer based out of Kolkata, working with For Films. He’s a graduate of Northwestern University.