In 1948, an unknown columnist named Satyajit Ray lamented the predicament of contemporary Indian cinema in The Statesman — “... production without adequate planning ... a penchant for convolutions of plot and counter-plot ... the practice of sandwiching musical numbers in the most unlyrical situations ...”He was, at the time, a commercial artist with an English advertising firm, making a name for himself in well-regarded Calcutta circles as a cover designer while writing about his favourite directors on the side. It would still be a year until his famous encounter with Jean Renoir on the sets of The River and seven till the release of Pather Panchali, but revisiting Ray today, one finds, regardless, a supreme clarity of artistic ideas in his criticism of Indian films all those years ago; ideas that would wash through all his subsequent works.

Conscious parallel between cinematic structure and musical structure

When interviewed about cinematic styles in later years, Ray would often make a comparison with music and talk about the “musical aspect of a film’s structure” before mourning the tone-deafness of most directors. This refers not merely to the use of sound and music in his films but also to a conscious parallel between cinematic structure and musical structure that he attempted to draw.

Ray found a filmmaking tradition of disparate entities thrust upon him — one of melodrama and excess in the films of (then) Bombay, a quieter artistic sophistication in the films of Calcutta’s New Theatres and the musical folk-dramas of jatra companies who drifted across the Bengali countryside.

And yet, tradition cannot be inherited, as T.S. Eliot famously wrote, but it must be obtained with great labour. One is unsurprised, therefore, to learn that Ray, an artist trained at Visva-Bharati and a director buttressed by years of carefully studying the Capras, Hustons and Eisensteins, was also first a lover of music. Born into an illustrious bhadralok family, Satyajit’s upbringing was typical of the scores of middle-class Bengali families who lived around him in Bakulbagan and Beltala.

A world where East mixed fiercely and fruitfully with the West

Growing up surrounded by Wodehouse, Homer and weathered copies of Sandesh while his Pigmyphone rattled with worn records of Bach and Mozart, he found himself in a world where East mixed fiercely and fruitfully with the West in art, philosophy and music. As a young man, it was Western classical music that catalysed some of his most influential relationships — with a British RAF employee and friends at Santiniketan, with his cousin Bijoya, whom he would later marry, and finally, with the world of films.

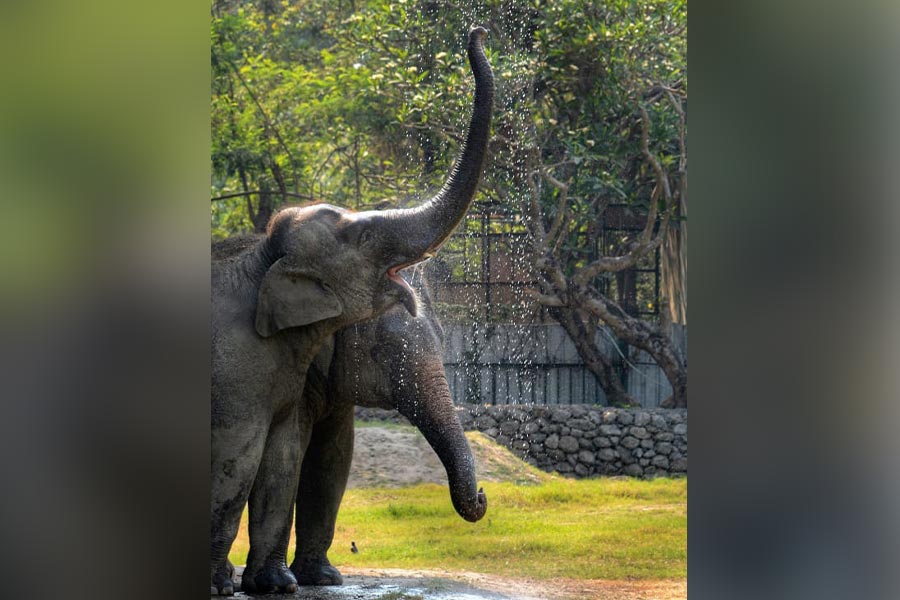

The characters in 'Aranyer Din Ratri' are all like distinct musical motifs in a Mozart composition

For long, he had admired the order of the Classical period, of the beauty in a Haydn concerto or a Beethoven symphony despite the rigidity of its compositional form. In particular, he revered the symmetry of the sonata form,a musical structure usually employed in the first movement of a piece with an exposition, a development and a recapitulation. His imitation of the sonata form can be seen on two levels: the actual soundtracks of his films, certainly, but also his plots which must have been loosely inspired by this outline. Some of his more cerebral, character-driven stories like Aranyer Din Ratri, a comedy of manners where nothing really happens, can be viewed entirely from this perspective. Ashim, Aparna, Jaya, Sanjoy — distinct musical motifs in a Mozart composition, their relationships and interrelationships — melodic interactions among these motifs, layering, texturing, changing key and mode, complications in plot rising like accelerated crescendos with harmonies and disharmonies, and the final car journey homeward — a code signalling a subdued return to the tonal centre and bringing with it a harmonic conclusion.

Driven by characters rather than revelry and action

Music is functional to Ray and not decorative. To his contemporaries, songs were meant to be musical interludes between moments in the story and were rarely responsible for furthering it at all. Ray’s films, on the other hand, are driven by characters rather than revelry and action; and yet, none but two of his characters ever properly sing. Instead, his music is connective; his soundscapes complement the plot and provoke deep emotion.

The beats of ‘ta ta thoi thoi’ in the opening credits of the film are an ironic commentary on Charulata’s out-of-step relation with Amal and her alienation

Keya Ganguly, author of Cinema, Emergence, and the Films of Satyajit Ray, draws our attention to a single, seemingly banal sequence from Charulata, the very first of the film, where the opening credits fade into the screen and a sitar plucks the tune of a popular song by Rabindranath Tagore, commenting on its intertextual referencing of the source of the film — Nasta Nirh, a novella written by Tagore himself in 1901. At the same time, there is a deeper foreshadowing to be found here. The song is about being in step, “ta ta thoi thoi” being the beats taught to dancers, but placed against Charu’s circumstances, her being out of step with Amal, her alienation from a glittering mansion in which she finds herself alone, the tune is a subtle but ironic commentary. A slight detail, but one that, to the conscientious viewer, enhances the perception of the film.

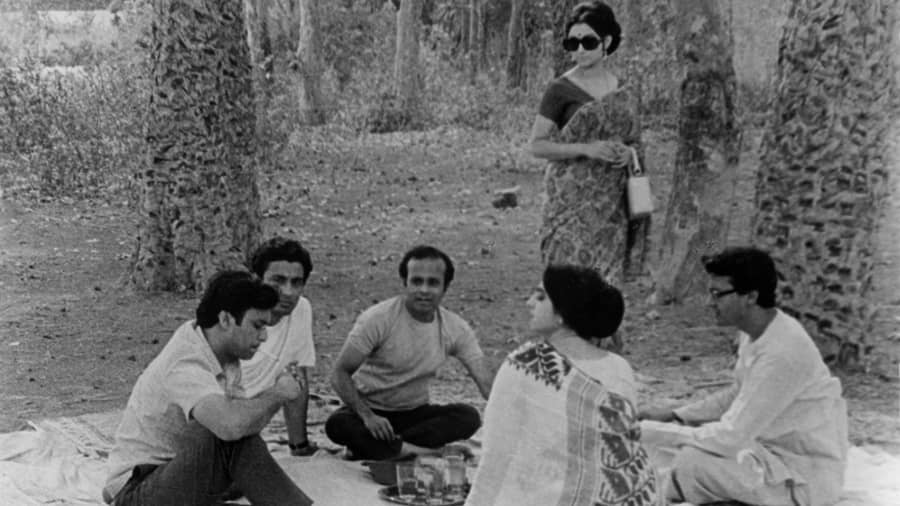

The elaborate Hindustani performances in 'Jalsaghar' are the perfect confluence of emotive and narrative functions

Ray’s music, therefore, acts not only as an accentuation of action but also an acceleration of it. It tunes the audience’s sensibilities while also performing an important narrative function. The elaborate Hindustani performances in Jalsaghar are the perfect confluence of these emotive and narrative functions. The scenes where Biswambhar reclines regally amidst a retinue of subordinates as a kheyal or a thumri resonates through the shimmering chandeliers of his music room reference recorded historical fact — that the patronage of extravagant, pleasure-loving landowners were critical to the survival and perpetuation of classical artists. Simultaneously, these sequences, when later contrasted with the images of a forgotten, forsaken Biswambhar, paint a sympathetic picture of a man watching helplessly as he fades into obscurity.

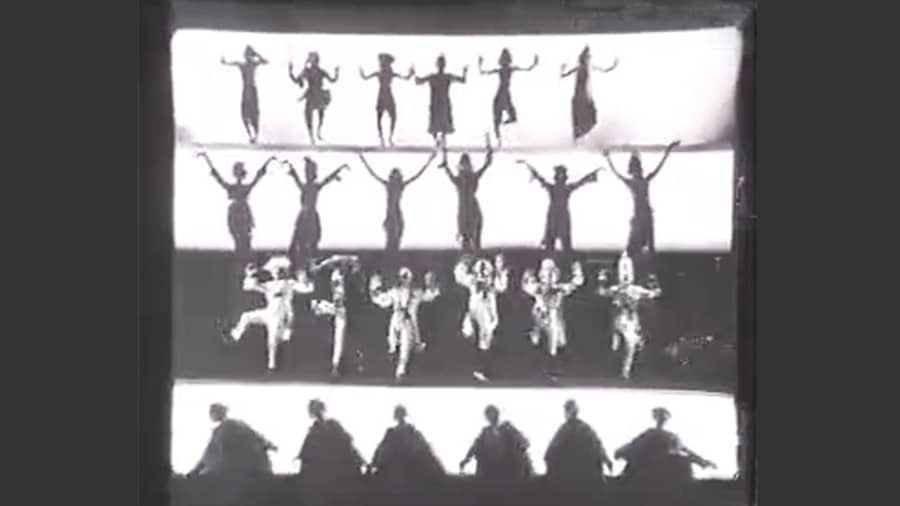

The famous dance of the ghosts in 'Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne' was accompanied exclusively by traditional percussion instruments

Despite his affinity towards Western classical, Ray’s stint at Santiniketan under the tutelage of Tagore had planted in him a fondness for the music of his native land. His fanciful musicals, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and Hirak Rajar Deshey, while surfacing his dexterity with words, are also effective parodies of Indian music styles and moods. The songs further the narrative organically, since they are tales about wandering minstrels, without compromising on the emotional value they hold. Viewers are delighted, for instance, by a terrified Goopy pleading with a tiger to a menacing raga-inspired melody in Hirak Rajar Deshey, while the famous dance of the ghosts in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne was accompanied exclusively by traditional percussion instruments, each distinct before building up to a rhythmic, pulsating crescendo.

Music, to Ray, deepens emotion, evokes mood and shades character

Music is simultaneously within film and without, suspended between the real and the unreal. The viewer knows that in real life music cannot sound out of nowhere; but at the same time, it is so irretrievably lost within the tapestry of what is filmic, that it is impossible to suitably dissociate it from the developments on-screen. Ray recognises this strange power of music to soothe and evoke, and, importantly, its ability to bridge the gap between narrative and perception, conveying an order of sensory experience that mere visuals cannot.

Music, therefore, to Ray, deepens emotion, evokes mood and shades character. Perhaps the closest analogue in European art would be Wagner’s notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk — the ‘total work of art’, where myriad art forms are not patched together clumsily but subordinated to a common theme and a common end. Tunes and melodies are introduced in association with a mood or a theme or, perhaps, even a character; they are woven in and out of the narrative, developed with harmony and texture, perhaps reintroduced at moments of thematic recapitulation. Bravura singing, senseless spectacle, music as ornament — these have no place in Ray’s conception of art; his sensibilities are too subtle, too sophisticated, too refined for that. Indeed, one gets the sense in Ray — as one does in Wagner, in Shakespeare, in the greatest of geniuses, in fact — that the work has been created in a single, miraculous stroke of the imagination, such that not an ounce of story is inessential, not a note of music out of place. Such perfection can be analysed in so many ways; it can be admired for its technical ingenuity; it can be dissected, scrutinised, spelled out and picked apart. But then, after all that is done, one can only fall silent — and let the films speak for themselves.

Sushen Mitra is a student of political science at St. Xavier's College, Kolkata, and is passionate about music and football.