For those tired of mankind’s ways, there is a great antidote — watch US space agency Nasa’s counter that measures how much distance Voyager 1 is putting between itself and the earth every passing second.

By September 7 evening, as the dust settled on the high drama and frenzied media coverage around Chandrayaan-2, Voyager 1 was well past 13,644,015,600 miles from home and travelling at tremendous speed.

Space isn’t totally silent but, as far as human hearing goes, it is quiet. Sitting on Earth, one’s day succumbing to everyday noises including the media’s, Voyager 1’s mission appears meditative.

Voyager 1 is among the fastest man-made objects and the farthest. Launched 42 years ago, the space probe hurtles quietly on in a manner that should put the fastest super bike and its coveted engine growl to shame.

Its story and existence, like space, forms a mute backdrop to all the drama surrounding India’s moon-landing effort.

The noise generated around Chandrayaan-2 contrasts with the quietness of the moon, too. The earth’s satellite has a scant atmosphere but no robust medium for sound waves to travel in. Our moon rover should be in a very quiet world, insulated from the publicity machinery back home.

The Americans had made a similar splash across the global media when Apollo 11 put their first men on the moon in 1969. Television hyped the story up; the radio and newspapers took it to places TV hadn’t yet penetrated.

In the roughly 50 years since then, the frontiers of manned space flight haven’t exceeded the moon’s distance from the earth. But on our planet, the machinery that disseminates information to every corner has ballooned.

Newspapers are more numerous, television beams its pictures worldwide, the radio is still around and, above all, the Internet is available 24x7 through multiple devices.

I was very small when Apollo 11 happened. Growing up, one saw photos of astronauts on the moon, in books. Whenever a documentary film on the subject reached town it was lapped up, for such visual records were hard to access.

In 1984, when Rakesh Sharma became the first Indian in space, we watched the telecast. Curiosity for space had survived because the media hadn’t carpet-bombed their audience with reports on the topic. And, most important, there was no herding or trolling to force a politically correct response out of us.

The subject breathed free. Much like the sky, free for all to gaze and marvel at and form their own questions.

Stories of scientific discoveries tell us about both success and failure. And the setback Isro has confronted in the final phase of Chandrayaan-2’s journey isn’t a full-blown failure by any yardstick.

So much of the mission has gone right. Not just that, the mission cost India slightly less than Rs 1,000 crore — a sum eminently capable of being found again in an economy already more than $2 trillion in size and now being groomed to touch $5 trillion.

Why then did we have to conclude this journey in a way that made it look like a melodramatic tearjerker, with consolatory hugs and pep talks by politicians and all? What were the rest of us doing there trying to own a narrative that should be left to scientists?

Right from the start, I had found myself tuning out news of Chandrayaan-2 because it seemed exactly where everyone was heading for political correctness. Centuries ago, the flat earth theory, the theory of the sun orbiting the earth — all these were politically correct too.

By September 7 evening, people across the spectrum — politicians, film actors, sportspersons — had closed ranks to commend and console Isro. It isn’t that the trend was wrong; the question is, why was it needed?

What if we simply allowed Isro room to reflect, correct and get back? We would do science a service if we remembered that the primary enemy of creativity is herd behaviour, authoring a mass response of the same type.

Without individual questions and creativity there is no science. The best way to support Isro is to keep the scientific temper alive.

It was hard to ignore the contrast between India’s media-inspired drama and the quietness and solitude of the moon, where the Chandrayaan-2 lander has come to rest.

For some reason, that mental image of lunar tranquillity felt more dignified, as did the minutes spent staring at Voyager 1’s odometer for relief from mankind’s ways. What else would you do if you wished to learn about space with none of the publicity-mongers in the frame?

The dictionary gives you several meanings of “space”, but the real thrill about space is expressed by two words that probably qualify it best: “Not us”.

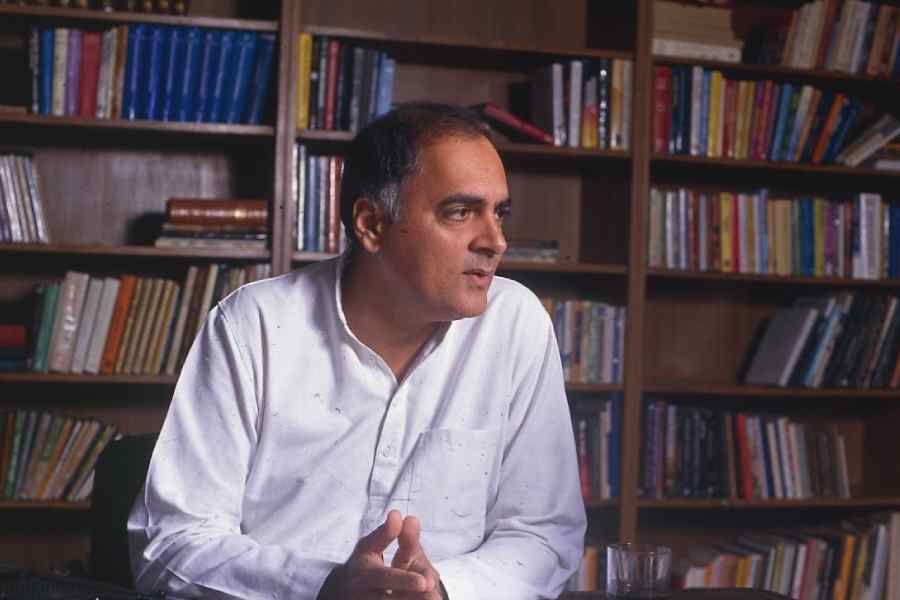

Shyam G. Menon is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai