As minister for Jammu and Kashmir affairs briefly in the V.P. Singh government, George Fernandes flew to Srinagar and vanished. The Valley was smouldering in the grip of a violent insurgency at the time and George’s slip to the security detail in a private car sent the powers scurrying.

Few would ever know where that jaunt took him — “to meet friends who can’t be named in places I cannot tell you” was all he ever said — but it soon became apparent the Union minister had disappeared to tryst with “the other side”, or advocates, political or militant, of Kashmiri secession.

Nothing ever came out of it, but George would underline that at 60 he still revelled in playing the maverick and resorting to the unthinkable.

A few years down the line, as minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, he came out of a meeting on ways to deal with expanding Naxalism and blithely, though privately, told a few of us: “You know such meetings leave me a little cold and conflicted, you know how long and how often I have been on the other side, waging battles against the state.”

George was then minister for defence. He was well aware he was dropping a clanger but he was too enamoured of playing the iconoclast even though, clearly, he had long molted out of that role and become the establishment.

George lived a fair part of his fabled public career mindfully oblivious of his fractured face, of the rupture between his vehement espousals against the evils of state power and his desperate embrace of it, of the succumbing of his rabble-rousing socialism to the palpably contrary purposes of the Sangh.

He would often bristle at the suggestion that he had compromised his principles for power, defected from fiery blue-collar rights mongering to the conformist black shirts. He would pull out the Lohia doctrine as defence — how his socialist mentor had made a compact with the Sanghis as counter to the Congress. In a life riven with beguiling chasms between the purported and the real, anti-Congressism remained a core constant to the end.

George never found it difficult to justify incompatible alliances because he thought it natural to make friends with enemies of the Congress.

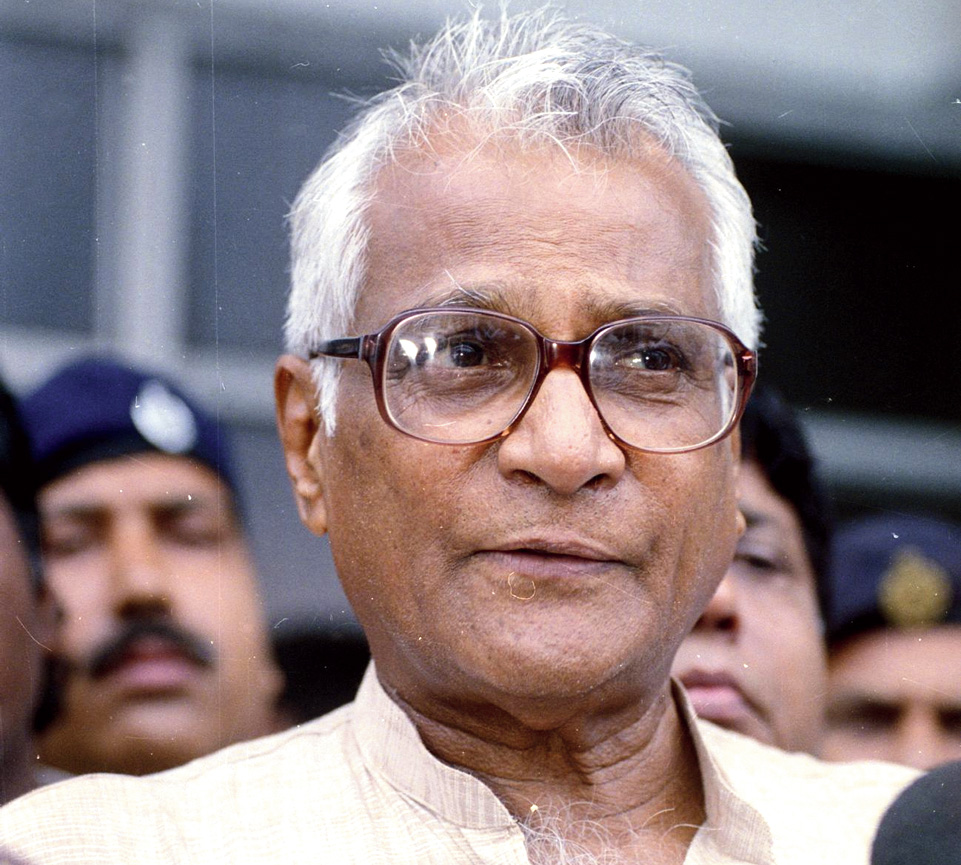

It was battling the Congress, after all, that George had become the unwashed street phenomenon that he was — his crumpled pyjamas, his unkempt khadi chappals, his carelessly curled forelock, his bristling remonstrations from whatever stage he mounted.

Indira Gandhi, well on her way to turning dictator in 1974, wouldn’t brook George’s unruly and rebellious ways. Here was a man who had brought Bombay to a standstill with the taxi drivers’ strike. Here was a man who would scale up his trade unionism and bring the railways to a halt. Here was a dangerous man, a daily burgeoning threat. She would take care of him.

Implicated in what came to be known as the Baroda Dynamite Conspiracy, George was hunted down, manacled and jailed.

It was wearing those manacles that George — a Mangalore Catholic aspiring to a career in the Church — would win one of the most stirring campaigns of the 1977 election that cast Indira Gandhi out of power.

It was fought in faraway Muzaffarpur in north Bihar. It was fought by ramshackle billboards of a chained George gnashing from behind Indira Gandhi’s bars. Muzaffarpur was won for George on a heady hero-worship that remains a legend all these years later.

By the time he’d stepped out of jail and become minister for industries in the Janata government, George was already a legend writ large on national consciousness, a bolt of inspiration to a whole school of wide-eyed political aspirants to whom he’d become “George Saheb”.

It was in Muzaffarpur too that George would fight his last election and miserably lose. By 2009, George had already been taken by a disabling cocktail of late-life ailments. He could barely walk, barely speak, barely even be deposited in the front seat of his campaign car where he would sit lapsed while a motley horde of loyalists screamed slogans nobody cared about any more. Least of all George.

It would have been a poignant late-life attempt to reclaim Muzaffarpur had it not been so pathetic. He had been denied a ticket by his pupil Nitish Kumar, then, as now, chief minister of Bihar. And soon he would be denied by the constituency that had made such a mascot of him.

It will never be known if George was willing, but someone around him was. It was a cortege of a campaign, a metaphor in some ways, of what George once represented and what had become of him, a brimstone turned to ashes.

Between the two Muzaffarpur campaigns — the scintillating one of 1977 and the unseemly 2009 smudge on all that shine — unravelled the capricious story of George Fernandes, the promise he flamed with and all that he left pitilessly famished.