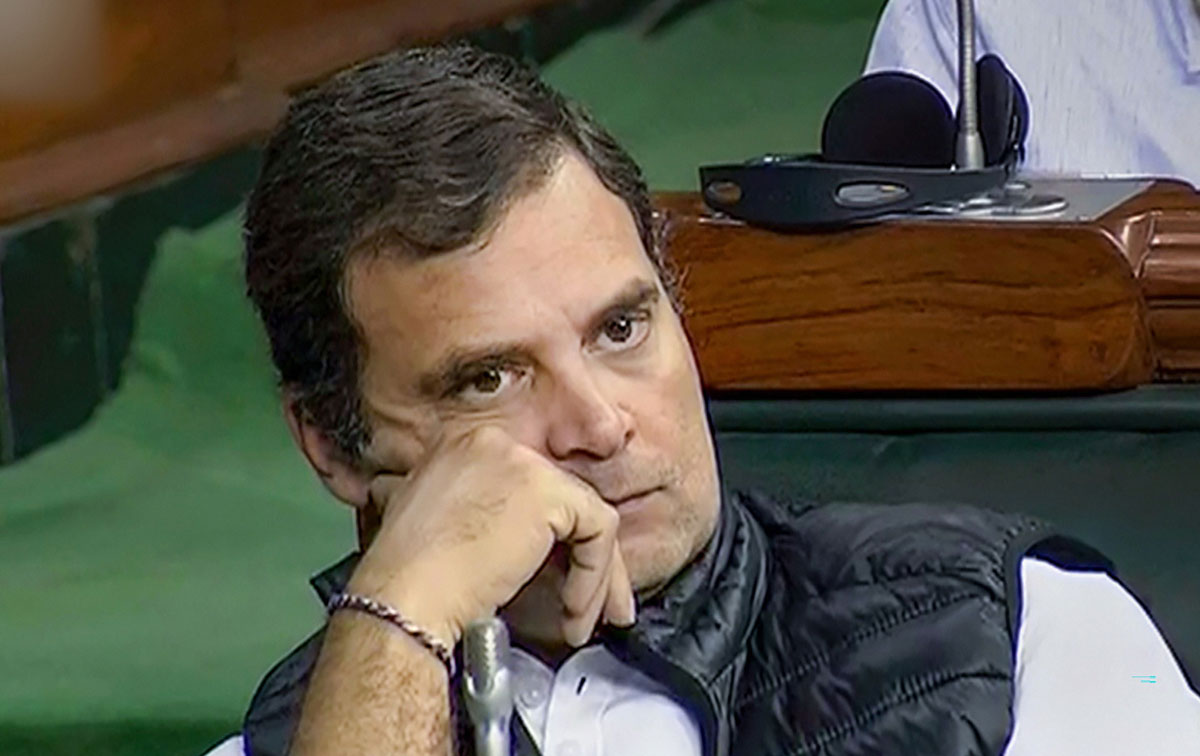

Fact: Rahul Gandhi is the Congress MP from Wayanad in Kerala.

Fact: Rahul Gandhi is not only the Congress MP from Wayanad in Kerala.

Fact: Rahul Gandhi is nobody in the hierarchy of the Congress party.

Fact: Rahul Gandhi cannot be nobody in the hierarchy of the Congress party.

Fact: Rahul Gandhi does not want to return as president of the Congress party.

Fact: Rahul Gandhi wants to return as president of the Congress party.

But he will do so when he believes the terms and time are right. Until then, the denuded Grand Old Party of India must lie disabled in the ineluctable paradoxes riven by one man’s whim.

The Congress is a family-held court and has best functioned as that for decades — command flows from the top, command is followed, and that is how what gets done in the Congress gets done. It’s all down to the Gandhi name and the de facto supremacies and supplications it enjoys. Take the Gandhis away and you may not be able to count the number of ways the organisation splits in a single breath. Rahul Gandhi has decreed that nobody from his family should be Congress president and has made it known that he remains unhappy Sonia Gandhi stepped in to take working charge when he left. But that is the way the Congress is. Rahul Gandhi’s decree is a death decree. Or, in the event that a non-family member does become party boss, it will be the fulfillment of a dead decree. Real power will still remain in the hands of the Gandhis, they are the essential glue to whatever remains.

Recall the day in March 1998 that Sitaram Kesri was removed as Congress president and Sonia Gandhi assumed charge — it was effected with the swiftness of a coup by the loyalist vanguard; almost its first act was for a group to barge into the 24 Akbar Road AICC headquarters, wrench off Kesri’s nameplate from the party president’s chamber and nail in Sonia Gandhi’s.

Rahul Gandhi — and this is least of all for him to deny — is a central pillar of that court. That central pillar has decided to position itself in a way the court cannot proceed.

A couple of days before Jyotiraditya Scindia’s abject defection to the BJP set off a flutter of speculation over what had led to it, and what could follow for the Congress, Opposition parties put out a joint statement demanding the release of all political detainees in Jammu and Kashmir. It did not carry the endorsement of the nation’s chief Opposition party. The reason? There was nobody in the Congress to take a call on whether to sign on or stay out. The signatory Opposition groups waited two days, then went ahead and made their demand public. “The party is in self-destructive stasis,” a senior Congress leader said, “the smallest decisions don’t get taken, or take inordinate time to get taken, or get taken in a manner that often reflects there is disagreement at the top. It is no secret, for instance, that Rahul Gandhi still does not approve of our power-sharing alliance with the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra. Were he still Congress president, the alliance would probably never have happened. He seems to want a moral politics, he says he cannot be bothered if that does not get him power, he says he has time.”

The question many in the Congress have been asking, with growing urgency, is whether the party itself has time. And whether Rahul Gandhi, being who he is and knowing that full well, has time for the party. The last time the Congress Working Committee (CWC) met — on the gravity and horrors of the Delhi carnage — he was absent. And that wasn’t the first time. Rahul’s absences, abrupt, often unexplained, and far too frequent for a man who willy-nilly is the face of the main Opposition party, exact a political price. “We have been in deep and consistent decline for nearly a decade now, we need strong leadership and direction, and for that we need a leader who is seen to be leading every day, every hour. That’s what Narendra Modi is able to do. But that never was the case with Rahul Gandhi, even when he was Congress president,” lamented a senior partyman, “He has made repeated promises to people to be among them, he has repeatedly belied that promise. After we got hammered by the Aam Aadmi Party the first time, he came out and said he will learn lessons from the defeat and produce results. Did he? Ever?”

Overwhelming opinion in the party is that Rahul should be blamed, rather than applauded, for owning responsibility for the series of electoral reverses ending in 2019 and quitting. “That was the time we faced our toughest challenge,” said a young partyman considered close to him, “That is when we wanted leadership most, and that is when he chose to walk away from the burnt down deck. He left the party wondering what next.”

Rahul himself seems unbothered by the what next. A careful reading of his lengthy resignation letter makes that plain. It is, in fact, a theoretical, even ascetic, rejection of power and electoral politics as he sees it. “My fight has never been a simple battle for political power,” he wrote, “we didn’t fight a political party in the 2019 election. Rather we fought the entire machinery of the Indian state, every institution of which was marshalled against the Opposition… Our democracy has been fundamentally weakened. There is a real danger that from now on, elections will go from being a determinant of India’s future to a mere ritual.”

He inhabits, and seldom omits to articulate, the central ideas of the Constitution and the politics of compassion, plurality and inclusion which he believes are gravely imperiled. His resignation missive had, in fact, presaged some of the darkness that has now come into open play. “The attack on our country and our cherished Constitution that is taking place is designed to destroy the fabric of our nation,” he wrote with cold clarity, “The stated objectives of the RSS, capture of our country’s institutional structure, is now complete… The capture of power will result in unimaginable levels of violence and pain for India. Farmers, unemployed youngsters, women, tribals, Dalits and minorities are going to suffer the most. The impact on our economy and nation’s reputation will be devastating…” He spoke too in that letter of his “commitment” to fight the challenge “as a soldier”.

But does his demeanour reflect those intentions? Has he been able to invent strategies — or display commitments — that will invoke that battle? Is he willing to give his worldview the legs and the energy to compete in the race, much less win it? Is the objective of power even in his crosshairs? He has kept his party effectively confounded on much of that. A former aide who worked closely with him post 2015, laughed out loud when asked to describe Rahul’s style of functioning and mindset in a sentence. “He is impatient, he is inattentive, he is inconsistent, he is excited by an idea one day and he has forgotten about it the next, he is great at procrastinating, he will shift positions, he will run away, one moment you think you’ve convinced him about something, the next moment he’s slipped out. He was right to feel frustrated by the so-called Sonia old guard, but he was party president for two years, enough time to have restructured. He either did not have the will, or failed at it, or merely let things drift because he did not want the responsibilities of taking full grip. Rahul Gandhi, he never completes the circle…”

But he is also capable of rounding things off with rough bursts of impetuosity. Like when he publicly tore up his government’s ordinance that sought to shield convicted politicians and pushed Manmohan Singh to the brink of resignation. Or when he abruptly arrived on the JNU campus to demonstrate solidarity with Kanhaiya Kumar and company. Both were acts of whim, both took the party by surprise, both were received in the party with disapproval. Rahul didn’t seem to care.

The crisis for the Kamal Nath government in Madhya Pradesh is only a collateral consequence of the departure of Jyotiraditya Scindia; its core message is for the Congress high command and Rahul Gandhi to absorb: the party is restive as never before and needs clarity, most of all from Rahul Gandhi. Congressmen are deeply unhappy about the way they are led — or not being led — and that displeasure and unease are not about this faction or that, they are widespread.

Notice the refusal of Sachin Pilot, deputy chief minister of Rajasthan, to attack Scindia for crossing the ideological battlelines to the BJP: “Unfortunate to see @JM_Scindia parting ways with @INCIndia. I wish things could have been resolved collaborately within the party.” That is his way of flare-signalling to accost the leadership’s attention; he too awaits “collaborative” resolutions, he has been cheesed off for being denied chief ministership, he may just have fired a warning shot. Shashi Tharoor probably believes he was the right pick for leader in the Lok Sabha, not Adhir Chowdhury; he too has been seeking clarification, through a transparent organisational election, if nothing else. The Congress wants something to move, a shake-up, a wake-up. Rahul Gandhi says go ahead, do it, he isn’t in the way. Ask Congress people what they think of that; privately, most will tell you.

Fact: Rahul has said that the Congress party should decide the new leadership and he shall lend his full support.

Fact: The CWC and all of the AICC rejected his resignation following the 2019 debacle and insisted he should stay on.

Fact: The party did decide.

Fact: Rahul did not heed the party.